The economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic are of an unprecedented scale in Europe. The twin supply-demand shock has resulted in the halting of production (at least partially) in many companies as employees cannot go to work and in a fall in consumption because of mobility restrictions. The decline in revenues has deteriorated companies’ cash positions, fostering an increase in payment delays – and, ultimately, payment defaults.

Many European countries have temporarily amended the legal framework of default procedures to deal with the crisis

In most European countries, payment defaults must be reported to the competent authority within a given deadline by the company director, who would otherwise be held personally liable. The authority will then initiate insolvency proceedings. However, in order to simultaneously protect the structure and the recovery capacity of their economies once the pandemic is under control, the vast majority of European governments have taken two major steps: the implementation of measures to support corporate cash flow – such as deferrals (or cancellations) of social security contributions and taxes, or state guarantees on loans granted by banks – and temporarily amending the legal framework that regulates insolvency proceedings.

The German government has proposed the suspension until September 30, 2020 of the obligation for company managers to initiate default proceedings within three weeks of the discovery of the insolvency or over-indebtedness situation. This measure could be extended until March 31, 2021 by a decree of the Federal Ministry of Justice. Spain has chosen to waive this requirement until December 31 (initially two months after the cessation of payments). In Italy, only the Public Prosecutor’s Office is empowered to open default proceedings until June 30.

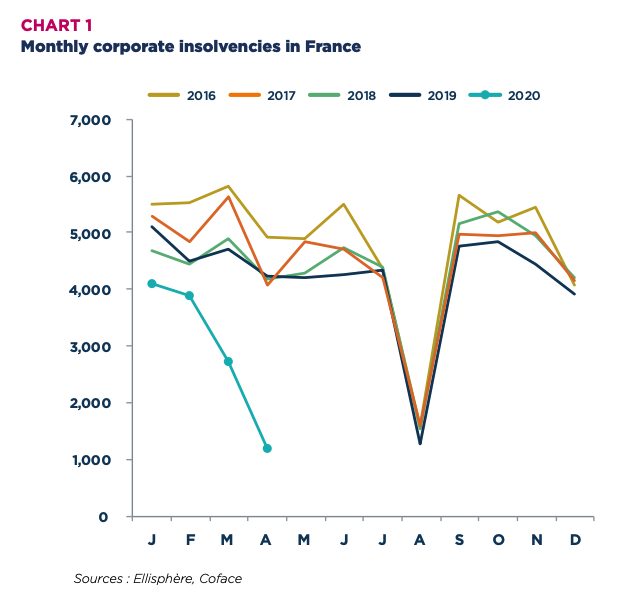

In France, until August 24, a company director is no longer obliged to begin insolvency proceedings within 45 days of the occurrence of the suspension of payments, failing which they will be liable for late filing for bankruptcy. Until that date, the existence or absence of suspension of payments will be assessed on the basis of the company’s situation on March 12. Concerning the UK, in the margin of the entry into force of the default bill, tabled on May 20, no default proceedings may be opened by creditors. If the measures in this bill were to come into force in June, then they would expire in July.

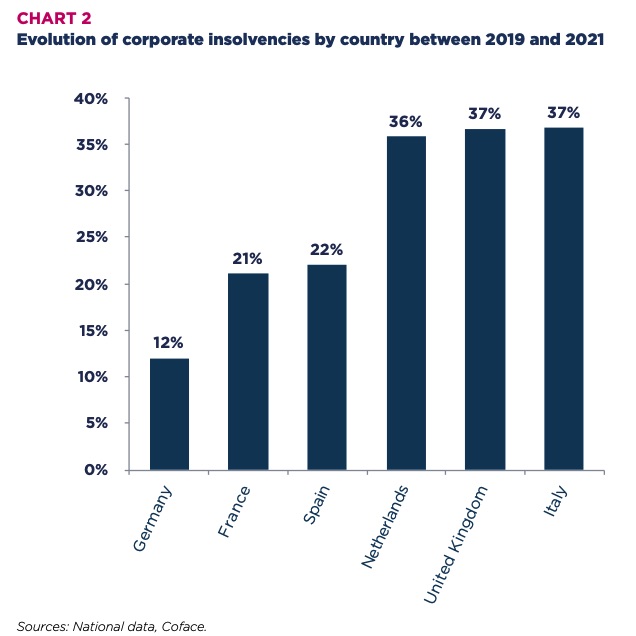

The Netherlands is the exception within Europe: the government has no implemented any emergency default measures since the beginning of the pandemic.

Nevertheless, given the magnitude of the economic shock and the temporary nature of these measures, the latter will not prevent a substantial surge in insolvencies once they expire.

Towards a differentiated and delayed growth of insolvencies in Europe, despite regulatory changes

According to Coface’s forecasting models, the number of insolvencies is expected to rise sharply across Europe in the second half of 2020, and in 2021. Germany, the least affected country, is still on track for a 12% increase in insolvencies between end-2019 and end-2021. France (+21%) and Spain (+22%) will be more affected by the crisis. However, the largest increases in the number of insolvencies are expected to occur in the Netherlands (+36%), the United Kingdom (+37%), and Italy (+37%).

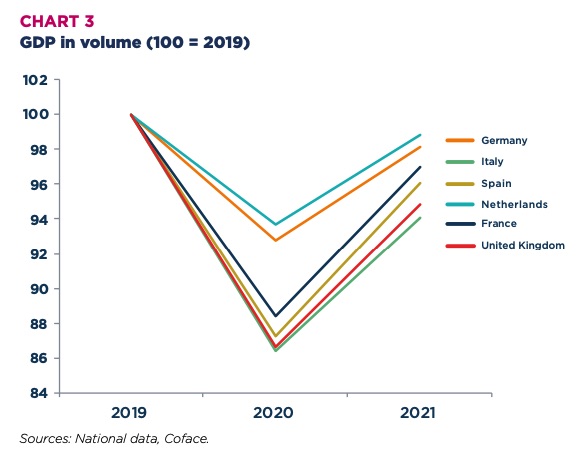

Although insolvency forecasts are roughly in line with growth forecasts, some discrepancies are apparent. The Netherlands and Germany should be the least affected countries, with GDP in 2021 less than 2% lower than in 2019. France and Spain would do worse with GDP less than 3% and 4%. The GDP of United Kingdom and Italy will likely be respectively 5% and 6% lower compared to last year.

In some cases, these discrepancies can be explained by the lack of a temporary amendment of insolvency proceedings (like in the Netherlands). The responsiveness of insolvencies in periods of economic contraction is also linked to the cost of the procedure (lower in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands).

Related: Video – Are there enough trade assets to finance in the market and are there liquidity issues?