Estimated reading time: 30 minutes

What are the top political, security, and economic trends and risks shaping Africa and the Middle East in 2025?

This research and analysis is provided by PANGEA-RISK and distributed in partnership with Trade Finance Global.

Five big trends in Global South country risk in the coming year

The shift in the US towards protectionism is a harbinger of an uncertain and increasingly fragmented year, amongst Western economic powers. In this context, Gulf states will increasingly grasp power and influence amongst the Global South. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries have already invested over $110 billion in the region. The United Arab Emirates has been particularly active, committing $110 billion to projects between 2019 and 2023, including $72 billion in renewable energy, as companies like DP World expand their logistics and port operations.

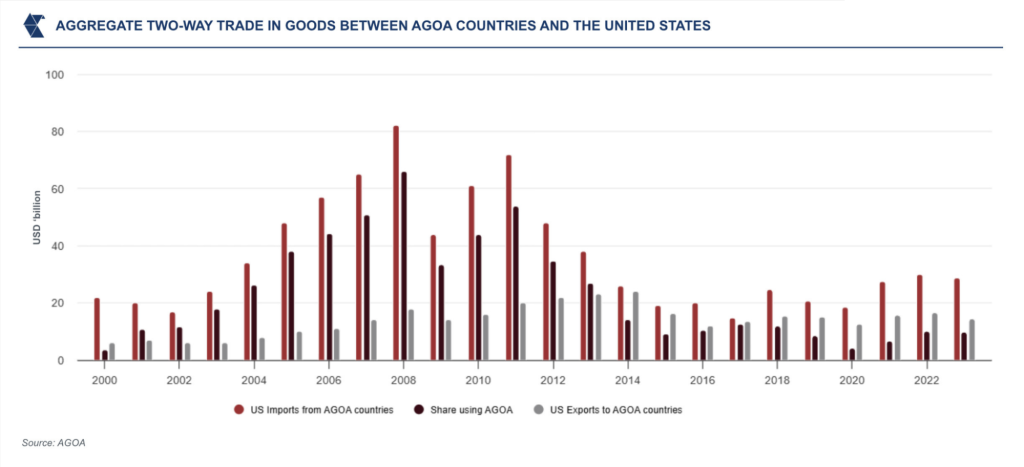

Regarding American protectionism, a critical moment will be the expiry of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), a preferential trading program designed to expand African countries’ duty-free market access and boost US-African trade. If the US Congress decides not to renew the AGOA, the trade competitiveness of African exports may be damaged.

This has been growing increasingly visible in the currency arena. China and other nations are actively promoting de-dollarisation, challenging US economic dominance through local currency trade and alternative payment systems like the Cross-Border Interbank Payments System in place of SWIFT.

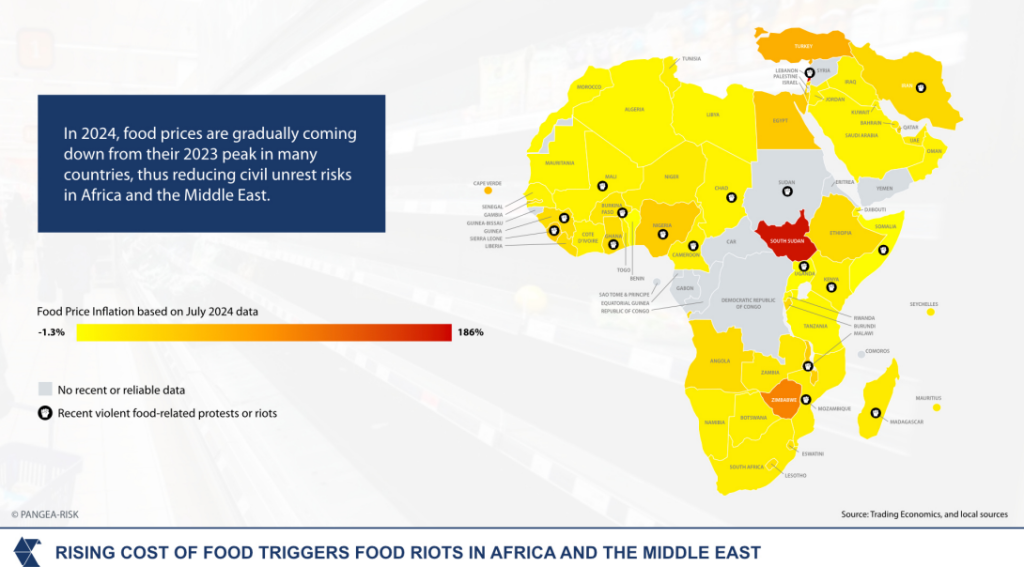

Economic opportunities in the Global South are tempered by significant challenges, including persistently high youth unemployment, elevated food prices, and the disproportionate impact of climate change. These factors could potentially trigger political instability, resource nationalism, and increased interference from global powers seeking economic and military influence.

In terms of investment in Africa, Saudi Arabia has been active in mining and agribusiness, Qatar in aviation, and Türkiye in aviation, ports, construction, and defence. Hopes for peace and normalisation in the Middle East are tentative, but more promising than ever. Regional actors have been leveraging the power vacuum left in Iran and Syria to secure strategic gains, for instance, by disrupting Hezbollah’s supply chains.

Seeking alternative global trade routes amidst political risk

As instability persists in Gaza, so too will Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping; and since maritime disruptions benefit the overland Silk Route, it is unlikely that China will contribute to preventing these attacks to further their Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The India-Middle East-Europe Corridor is a complementary rather than competing corridor; similarly, western corridors like the European Union’s (EU) Global Gateway project will struggle to compete with the BRI’s more than $1 trillion.

Rising inflation worldwide has been caused by supply chain disruption, climate change, tariffs, and sanctions. The persistently high cost of living has been exacerbated by stubbornly high rates of youth unemployment, a common feature of fast-urbanising emerging markets. In this context, global food prices were hit hard, remaining almost 30% higher in 2024 compared with pre-pandemic levels. Multilateral organisations attempt to combat food insecurity, but the problem is exacerbated by infectious diseases that arise in conflict areas.

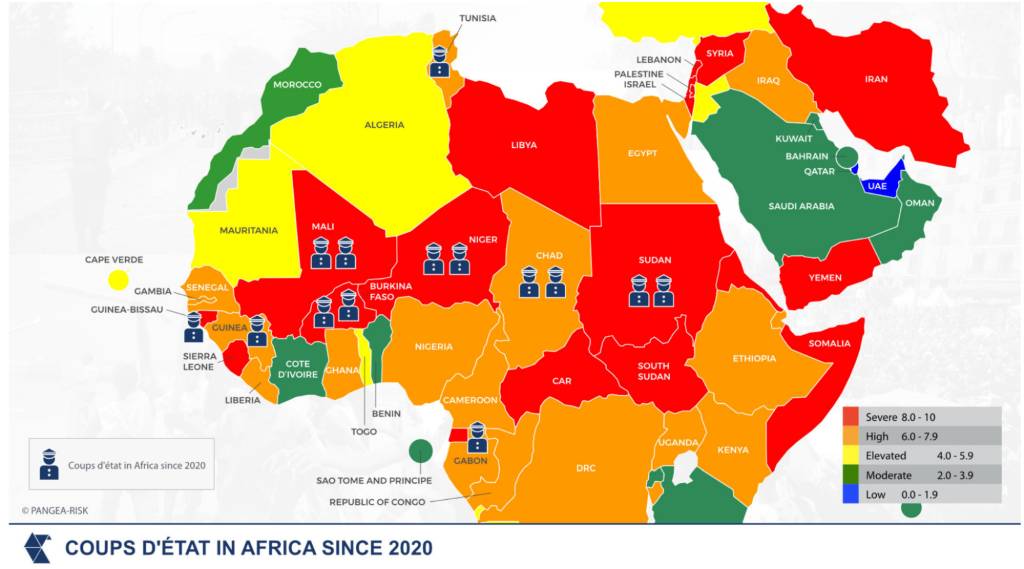

In 2025, key elections in Egypt, Iraq, Tanzania, Malawi, and Ivory Coast will be critically influenced by these key socioeconomic grievances. Countries with weak institutions like Niger, Togo, and Gabon face potential military interventions or election disruptions, continuing a pattern of political instability observed since 2019. The electoral landscape will be further complicated by a resurgence of resource nationalism, with governments in the Sahel and Senegal arbitrarily challenging international investment contracts, imposing unexpected taxation, and potentially expropriating state assets.

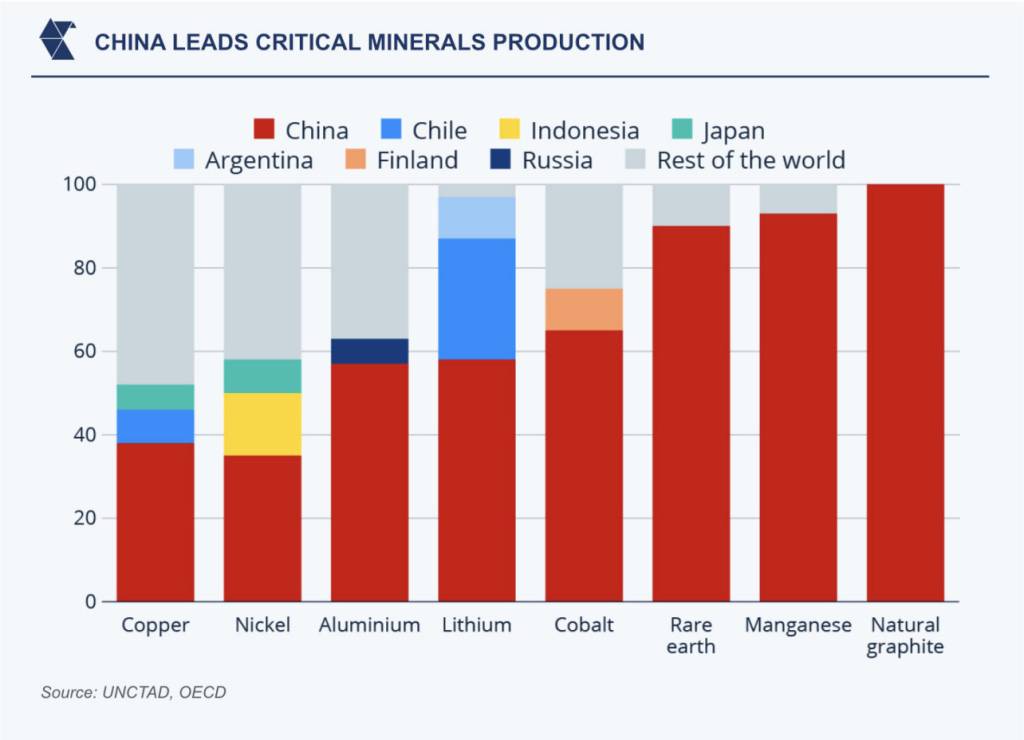

The situation differs sector-by-sector too. The critical mineral industry is exposed not just to extreme climate and maritime disruption, but also geopolitical drivers. Coups in Niger and Gabon in 2023 showed the vulnerability of supply chains for critical resources like uranium and manganese.

Finally, vulnerable regions are dramatically destabilised by rising temperatures, erratic rainfall, and desertification fuelling food insecurity, mass displacement, and resource-driven conflicts across the Sahel, Levant, South Asia, and Central and southern Africa. Militant groups are exploiting these environmental vulnerabilities by controlling water sources and recruiting from marginalised communities, thereby undermining government authority.

The central Sahel countries—Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger—are particularly affected, allocating substantial resources to military campaigns while experiencing unprecedented violence and climate-induced displacement. The number of internally displaced persons has surged substantially over the past decade, with this trend expected to accelerate as environmental conditions deteriorate.

Going forward, the need for ‘grey swan’ assessments to mitigate country risk are necessary: that is, by reasonably assessing improbable but predictable, high-impact scenarios. A ‘grey swan’ in 2024 was the sudden fall of the Syrian regime, and 2025 could see a seriously weakened Iranian military-clerical order or on the flip side, a stable unified government in Libya.

Top 10 elections to watch in 2025

2024 was often termed the ‘year of elections’, with some of the world’s biggest democracies taking to the ballot – including India, the UK, and the US. But in 2025, some significant and impactful elections will occur across frontier and emerging markets.

The next year of elections will likely be shaped by governance challenges, political transitions and mounting socio-economic frustrations, with some governments potentially using legislative means to maintain control whilst restricting opposition. In fragile democracies and post-military states, inadequate preparation and weak institutions may increase the likelihood of disputed results, particularly where there are existing political tensions and polarised voters. Economic difficulties including inflation and unemployment could fuel civil unrest and demonstrations, especially as opposition groups capitalise on public discontent to challenge governments that suppress dissent.

Here are ten to watch, with factors potentially contributing to instability highlighted.

Cameroon

Cameroon’s political stability is at risk due to the lack of a clear succession plan for ageing President Paul Biya, whose departure could create a power vacuum and potentially prompt military intervention. Rising political and socioeconomic grievances, coupled with election delays and intensified repression, increase the likelihood of opposition-led protests and the risk of military mutinies or even a coup ahead of the 2025 presidential election expected by October.

Cote D’Ivoire

President Alassane Ouattara’s intentions for a fourth term remain unclear, and opposition divisions hinder the likelihood of a unified candidate for the October 2025 election. The risk of civil unrest is elevated, driven by potential repressive measures, a possible fourth-term announcement, and socioeconomic grievances like the rising cost of living, which may fuel protests and strikes.

Egypt

The upcoming legislative elections in November 2025 are expected to solidify President Abdel Fattah Al Sisi’s grip on Egypt’s political and economic systems, with the pro-government Nation’s Future Party likely to maintain dominance. However, Egypt’s deepening economic crisis, marked by inflation and currency depreciation, raises the risk of abrupt policy changes, which could affect businesses and investors; furthermore, sporadic unrest may still emerge from mounting economic grievances despite strong state control.

Gabon

Gabon is set to hold general elections by August 2025, marking a return to democratic rule following the 2023 coup led by interim president General Brice Oligui Nguema. While Nguema’s likely candidacy and the new constitution enabling a potential 16-year rule raise concerns about prolonged military influence and opposition intimidation, his strong public support as a liberator from the Bongo family’s rule reduces the immediate risk of significant unrest.

Georgia

The atmosphere for Georgia’s 2025 local elections is set to be highly polarised. The ruling Georgian Dream party expected to use its institutional control to maintain power amid allegations of voter suppression, media bias, and opposition intimidation. Public discontent over governance and the suspension of EU accession talks, alongside fears of a shift toward Russian influence, may fuel opposition efforts to mobilize voters and could trigger further unrest, especially in urban areas.

Iraq

Muqtada Al Sadr’s return to politics could potentially challenge the dominance of the Iran-backed Shia Coordination Framework (CF). This could reignite factional rivalries within Shia blocs and increase the risk of violence, while amended electoral laws favouring established parties and accusations of manipulation may further erode political trust and fuel unrest.

Malawi

Malawi’s political landscape is expected to remain volatile leading up to the 2025 general election, with growing public frustration over economic hardships and slow anti-corruption progress fueling the risk of unrest. The election is shaping up as a contest between alliances led by the ruling MCP and the opposition DPP, but no single party is likely to secure a majority, making smaller parties and independents key to forming the next government.

Niger

Political instability in Niger is likely to persist: General Abdourahamane Tiani’s military junta is growing isolated from Western and regional partners, and strengthening ties with Russia and China. Delayed national dialogue, political repression, and deteriorating economic conditions fuel public discontent, raising the risk of civil unrest, particularly if elections planned for 2025 are not held.

Tanzania

Tanzania’s ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) is poised to maintain power in the 2025 general election, with President Samia Suluhu Hassan running for her first full term. While her business-friendly policies are expected to benefit foreign investors, the CCM’s reliance on authoritarian tactics to suppress dissent may fuel political tensions, though these are unlikely to significantly disrupt the broader business environment.

Togo

President Faure Gnassingbé and the ruling UNIR party are set to maintain their dominance in Togo, with a fragmented opposition and key critics detained, enabling Gnassingbé to potentially stay in power until 2033. While public frustration over economic mismanagement, political repression, and security challenges may fuel sporadic protests, particularly in Lomé as the 2025 election approaches, the opposition’s divisions and waning support reduce the likelihood of a significant uprising.

Trump presidency implications for Africa

The economic nationalism that incoming US President Donald Trump promises will have a varied impact across the African continent. Undoubtedly, 2025 will see new approaches to trade dynamics, development financing, and security partnerships.

It’s uncertain whether Trump will renew the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which expires in 2025. The act provides eligible sub-Saharan African countries with duty-free access to the US market for selected products. Moving away from unexclusive agreements, South Africa, the largest beneficiary of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), might risk losing its duty-free access to the US market due to its foreign policy positions regarding Russia and Israel, which some US officials perceive as conflicting with broader American global interests.

The proposed isolationist, “America First” economic strategies could indirectly affect African economies through potential increases in US inflation, driven by factors such as tariff increases, tax reductions, and domestic reshoring efforts. It also suggests potential reductions in foreign aid and a diminished commitment to climate resilience initiatives across the continent; the administration’s sceptical stance on climate change could further complicate development and sustainability efforts in African nations.

The security front

Trump’s apparent commitment to the Middle East and Ukraine means it’s unnlikely that the US will provide military assistance towards escalating insecurity in the Sahel Region. Perpetrated by insurgent groups under the governance of military juntas in Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, diplomatic relations between nations in the region and amongst their Western partners have substantially deteriorated—a trend unlikely to improve under a Trump administration.

In the Middle East, efforts to facilitate Saudi-Israel normalisation would remain a key diplomatic objective. Trump would likely endeavour to incentivise Saudi Arabia through commercial opportunities, arms sales, and targeted security assurances to encourage cooperation with Israel. However, Saudi leaders must navigate pressures concerning Palestinian sovereignty and the contentious issue of Israeli settlement expansion, amongst others.

Trump’s policy towards Iran is anticipated to maintain and potentially escalate the maximum-pressure sanctions regime, with minimal diplomatic engagement. This approach is designed to curtail Iran’s economic capabilities, thereby limiting its regional influence, nuclear development prospects, and capacity to support allied militias.

Iran may respond to perceived threats by strategically deploying its regional proxies and advancing its nuclear programme: a confrontational stance could potentially destabilise the already fragile geopolitical balance in the Middle East.

COP29 bringing tensions to the fore

International climate finance negotiations at COP29 in Azerbaijan have revealed tensions between Western countries and emerging economies. Western nations are pressuring China and Saudi Arabia—both still classified as ‘developing’ economies—to increase their financial contributions to climate initiatives. China is leveraging the G77 group of developing countries to resist these demands, although the G20 has tentatively agreed to redefine ‘developing’ economy classifications, which could expand the pool of contributing nations.

Despite these negotiations, establishing a New Collective Quantified Goal exceeding $1 trillion annually from 2025 remains challenging. By 20 January 2025, a more comprehensive assessment is expected, aimed at helping members prepare for the potential commercial implications of the incoming administration across Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

African governments pivot to domestic markets amid external financing constraints

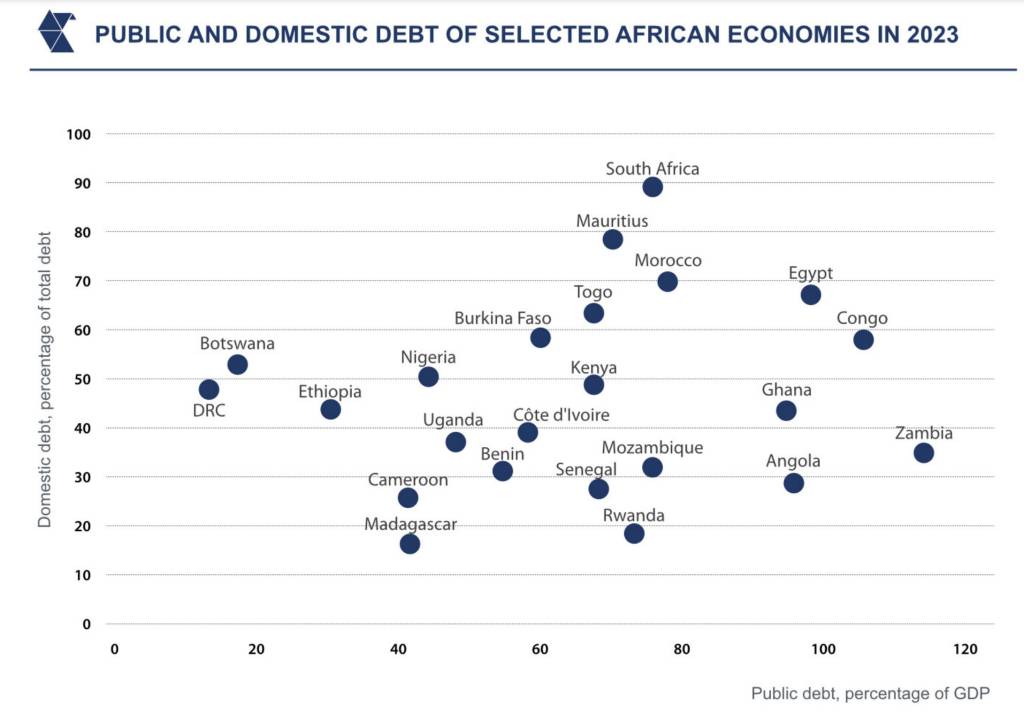

The borrowing patterns amongst African nations are shifting significantly, with governments increasingly turning to domestic markets as their access to international capital becomes more restricted.

As domestic dependence drives fiscal uncertainty, his trend is raising concerns about debt sustainability on the continent.

Debt servicing costs strain national budgets

Sub-Saharan African countries are projected to spend $74 billion on debt servicing in 2024, compared to $17 billion in 2010. This exponential increase is forcing governments to make difficult choices between debt obligations and essential services.

The volume of debt is a secondary concern, compared with the structural weaknesses which this burden brings to the fore. Along with the debt crisis, the continent simultaneously faces the challenge of raising $1.4 trillion in climate adaptation financing by 2030, further complicating fiscal management.

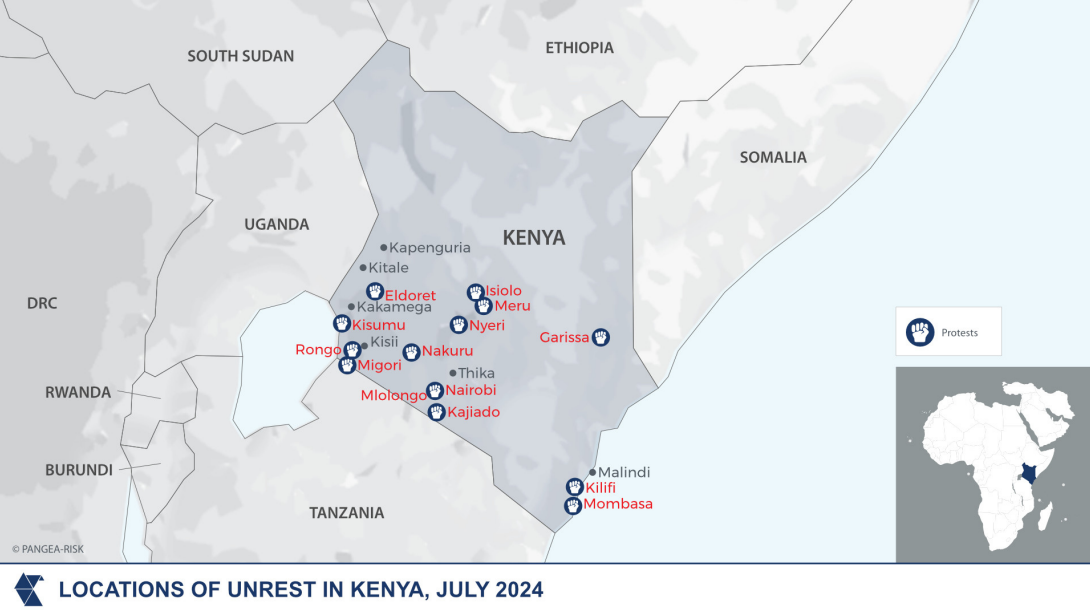

Kenya’s debt challenges exemplify the broader regional trend. The country’s debt-to-GDP ratio has risen from 40% in 2013 to 70% in 2023, with debt servicing now consuming 68% of fiscal revenue. Much of this debt can be attributed to mega infrastructure projects bringing insufficient returns: these investments are incompatible with Kenya’s informal sector-dominated economy. The banking sector holds 45% of the government’s $41 billion domestic debt, raising further concerns about systemic risks.

Kenya’s political instability has limited the country’s capability to raise funds. Widespread anti-tax protests in July meant that Kenyan tax collection as a proportion of GDP has stagnated at 15.2%; President William Ruto’s intended Finance Bill, predicted to raise an extra $2.7 billion, has been withdrawn as a result. Such tensions have instigated investor concerns over debt default risks: between June and October, auctions of seven out of nine longer-dated Kenyan bonds were undersubscribed, while the two oversubscribed auctions were issued with an average yield of above 18%.

Egypt’s situation says much about the relationship between the national banking sector and sovereign debt. While external debt has declined by 5% to $15.9 billion, domestic debt continues to rise rapidly – projected to escalate by 32.7% in the 2024/2025 fiscal year.

The increasing reliance on domestic debt has, in theory, reshaped African banking sectors. It’s reduced private-sector lending, increased vulnerability to government fiscal health, and brought the need for careful liquidity management.

In spite of growing exposure to sovereign debt, the Egyptian banking sector has remained resilient. The sector holds 60% of government securities and maintains strong liquidity with loan-to-deposit ratios around 52%.

Promising policy responses: innovative financing solutions

In Nigeria, domestic debt has reached over $70 billion, accounting for 62% of total public debt. But some recent reforms add optimism to the landscape, including a fuel import bill reduction from $600 million to $50 million monthly; the elimination of fuel subsidies, saving $3.3 billion annually; clearance of $7 billion foreign exchange backlog; and a new Dangote Refinery deal enabling Naira-denominated transactions.

In this manner, African governments are implementing various strategies to manage debt challenges:

- Increased use of trade finance solutions and export credit guarantees

- Exploration of green and blue bonds

- Enhanced regional trade through AfCFTA mechanisms

- Pursuit of concessional loans from multilateral institutions

—

The outlook for Africa’s debt sustainability remains challenging. While domestic borrowing offers a temporary solution to external financing constraints, the high costs of this strategy may prove unsustainable. Success will depend on governments’ ability to implement effective fiscal reforms while maintaining access to diverse funding sources. The upcoming IMF and World Bank annual meetings in October 2024 will be crucial in addressing these challenges and developing more comprehensive solutions to Africa’s debt crisis.

Buoyant interest in African critical minerals spurs investments in infrastructure and logistics

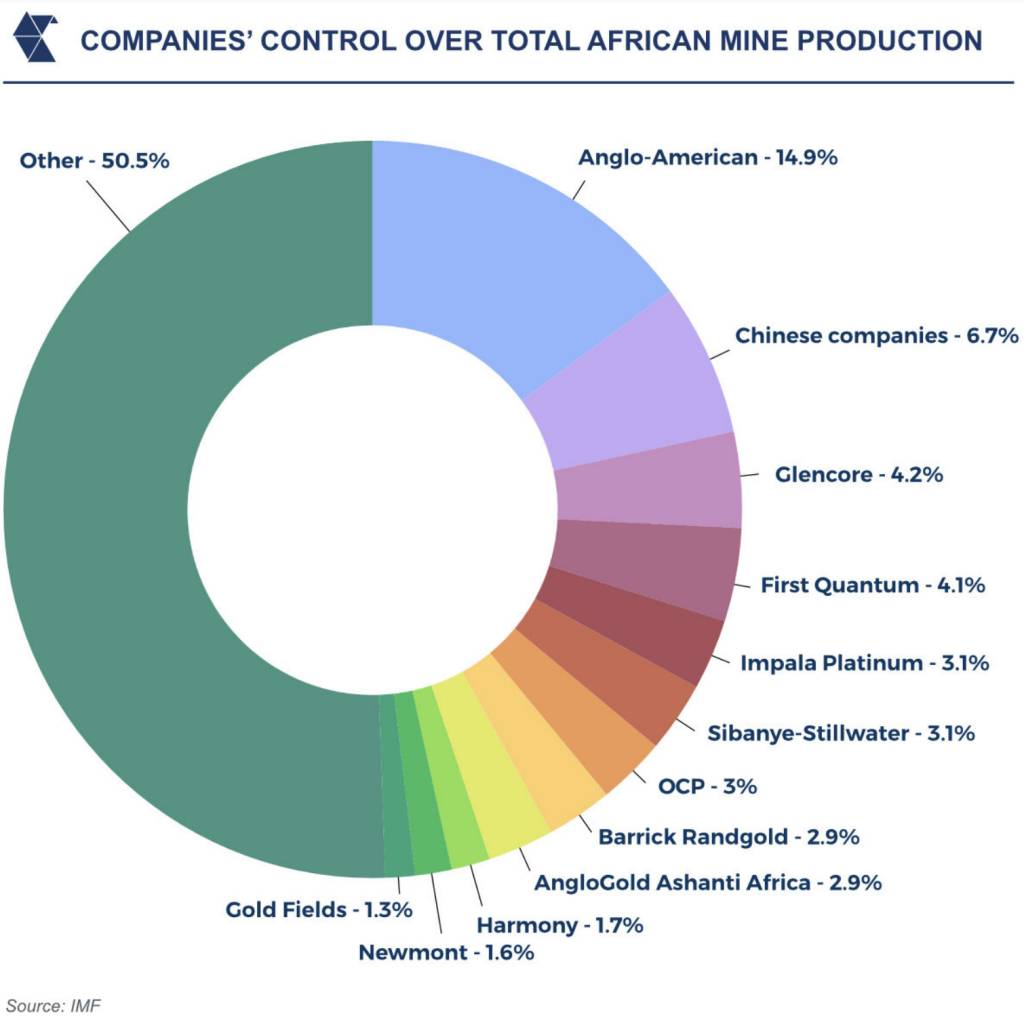

Africa’s critical minerals sector is experiencing a strategic shift in global investments, with the United States and Europe promoting projects to challenge China’s dominance and diversify partnerships.

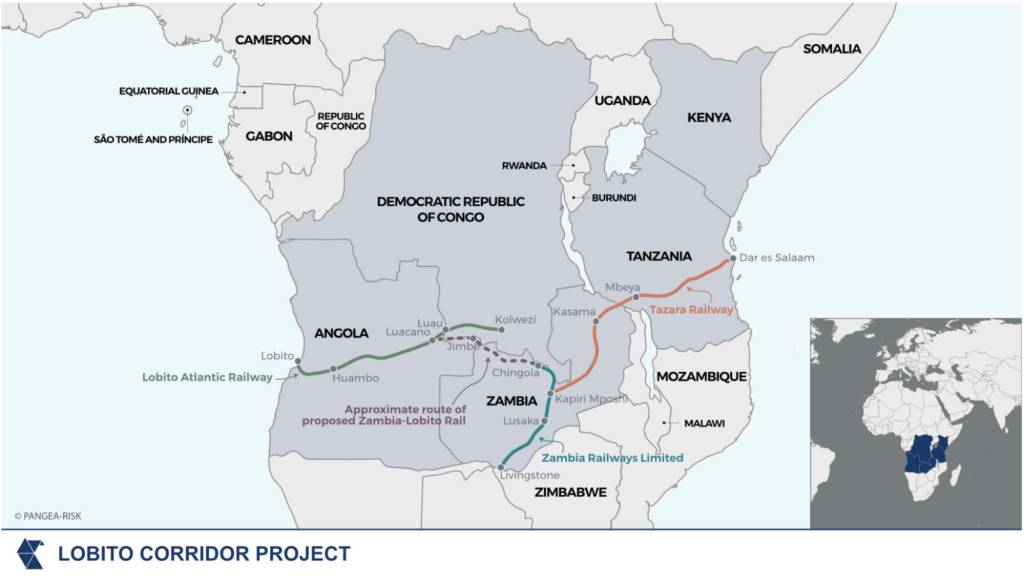

Investment profile shifts: The Lobito Corridor

The Lobito Corridor project, traversing Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Zambia, exemplifies this shift. It aims to link copper-rich regions to Angola’s Atlantic port of Lobito through railway rehabilitation and construction.

The US International Development Finance Corporation approved a $553 million loan for the Lobito Atlantic Railway in June 2024. The Lobito Atlantic Railway consortium, comprising Trafigura, Mota-Engil, and Vecturis, was awarded the concession to operate the rail line. They plan to invest $555 million in the Angolan and Congolese railway operations over a 30-year management period.

China continues to accelerate its acquisition of crucial mining assets in Africa. The Chinese firm JCHX Mining Management is nearing completion of a deal to purchase 80% of Zambia’s Lubambe copper mine.

African countries are implementing regulatory reforms to attract global stakeholders and enhance value chains. Zambia has attracted $10 billion in mining investments over the past three years, driven by the 2022 Mineral Royalty Tax Reform. Zimbabwe has banned the export of raw lithium to encourage domestic value addition, aiming to capture 20% of global lithium demand and build a $12 billion economy by 2030.

Infrastructure deficits, particularly in transport and energy, are driving governments to engage in public-private partnerships and invest heavily in rail and logistics networks. West Africa faces some of the highest international transport costs, with container transportation costs ranging from 1.5 to 2.2 times higher than the global average.

Large-scale infrastructure projects are underway across the continent. Guinea’s $18 billion Trans-Guinean railway project involves a joint venture between the government, Rio Tinto Simfer, Winning Consortium Simandou, and Chinese investor Baowu. The project includes over 600 kilometres of railway and shipping infrastructure.

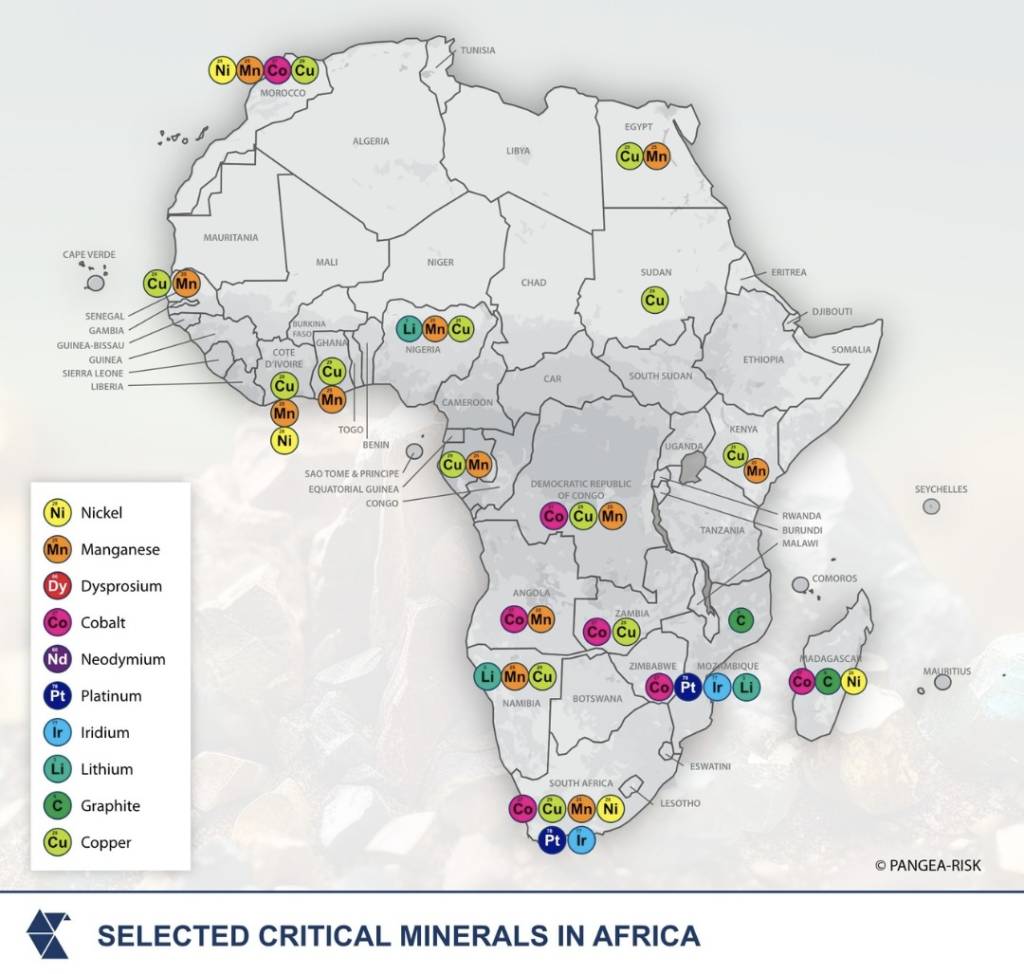

Africa holds significant reserves of critical minerals:

- South Africa possesses 80% of the world’s platinum group metals and 70% of its manganese reserves;

- Morocco has 70% of global phosphate reserves;

- The DRC boasts the largest cobalt reserves;

- Guinea-Conakry ranks second in global bauxite reserves; and

- Gabon holds the second-largest manganese resources.

In spite of this, it lags behind in terms of global critical mineral production.

Despite its potential, Africa has been underfunded in exploration compared to other regions, attracting only 10% of global exploration budgets in 2022. However, the continent’s estimated 30% share of global critical mineral reserves positions it to gain from rising demand for resources such as nickel, cobalt, and lithium, projected to increase up to ten-fold by 2050.

Countries like Kenya and Botswana are taking steps to improve their appeal to investors. Kenya is conducting large-scale geological mapping, while Botswana’s digital permitting reforms have cut permit times to 20-40 days.

—

The global demand for critical minerals shows no signs of slowing, making it likely that investment in African infrastructure will increase. If countries can align their regulatory frameworks with global investor expectations and develop better infrastructure, this likelihood will become a certainty.

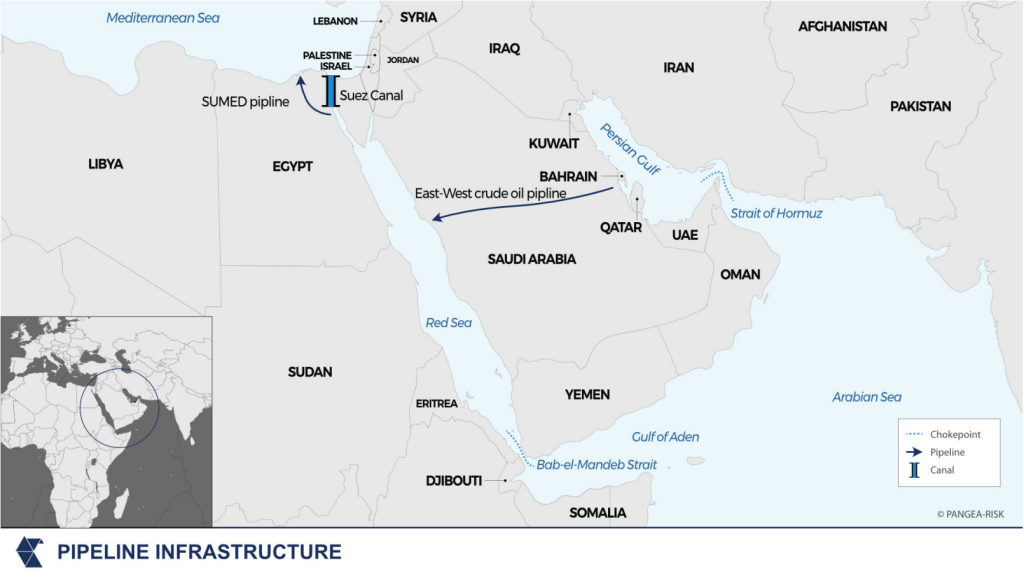

Heightened risks in the Strait of Hormuz and the Horn of Africa amid regional conflicts

Recent escalations in the Middle East presage maritime insecurity with far-reaching implications. At its heart lie the Strait of Hormuz and the Horn of Africa, both of which play crucial roles in international maritime security and global energy supplies.

The Strait of Hormuz: A strategic chokepoint

Tensions between Israel, Iran, and their respective allies have been a defining feature of Middle Eastern geopolitics for decades. Recent escalations have brought about – often asymmetrical – responses in retaliation.

The Strait of Hormuz is a key area caught in the crossfire. This narrow waterway, located between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman, is one of the most strategically important maritime chokepoints in the world. Approximately 20% of the world’s petroleum passes through the Strait of Hormuz, making it a critical artery for global energy supplies.

Historically, the Strait has been a flashpoint in the tensions between Iran and the United States. Iran has repeatedly threatened to close the Strait in response to perceived aggressions, particularly during times of heightened tension over its nuclear program.

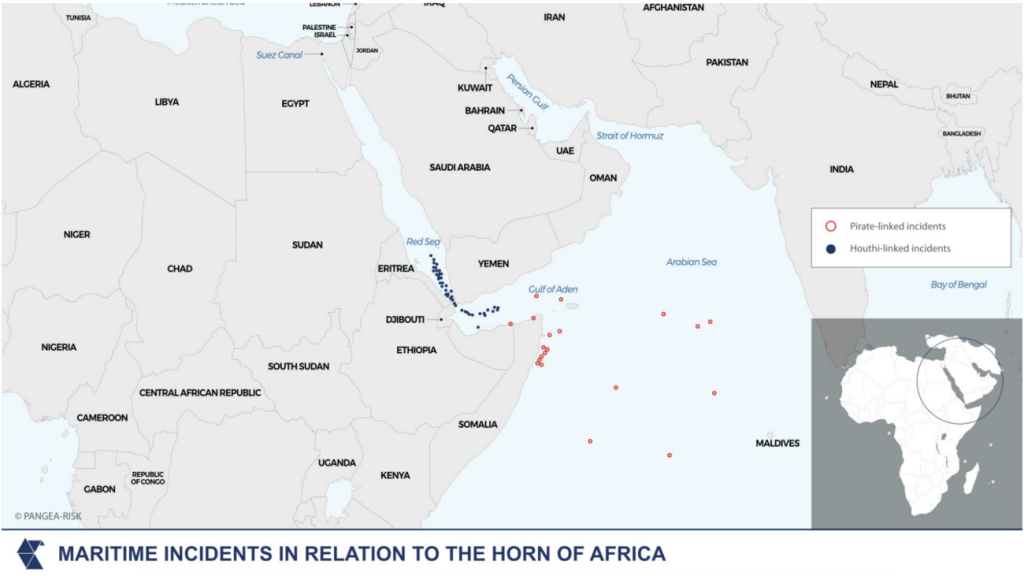

Although Iran has not explicitly threatened to blockade the Strait in the current context, its support for proxy groups such as the Houthis in Yemen, who have been active in attacking ships near the southern entrance to the Red Sea, indicates their disposition to disrupting global shipping to achieve its strategic goals.

The spillover of violence in the Strait of Hormuz poses a serious threat to global energy supplies. Iraq relies entirely on maritime routes for its oil exports from Basra since its Mediterranean pipeline has been closed for over a year; it is highly dependent on passage through the Strait of Hormuz. Kuwait, Qatar, and Bahrain also have no alternative but to ship their oil through this critical waterway.

Most of this oil is destined for Asia, so Western polities are somewhat insulated. Saudi Arabia, the largest oil exporter through the strait, has recently diverted shipments to Europe using a 1,200 km pipeline across the kingdom to a terminal on the Red Sea, thereby avoiding the Strait of Hormuz and the southern Red Sea. Similarly, the UAE exports 1.5 million barrels of crude per day via a pipeline to the port of Fujairah on the Gulf of Oman.

Nonetheless, the broader risk to global energy supplies remains prevalent.

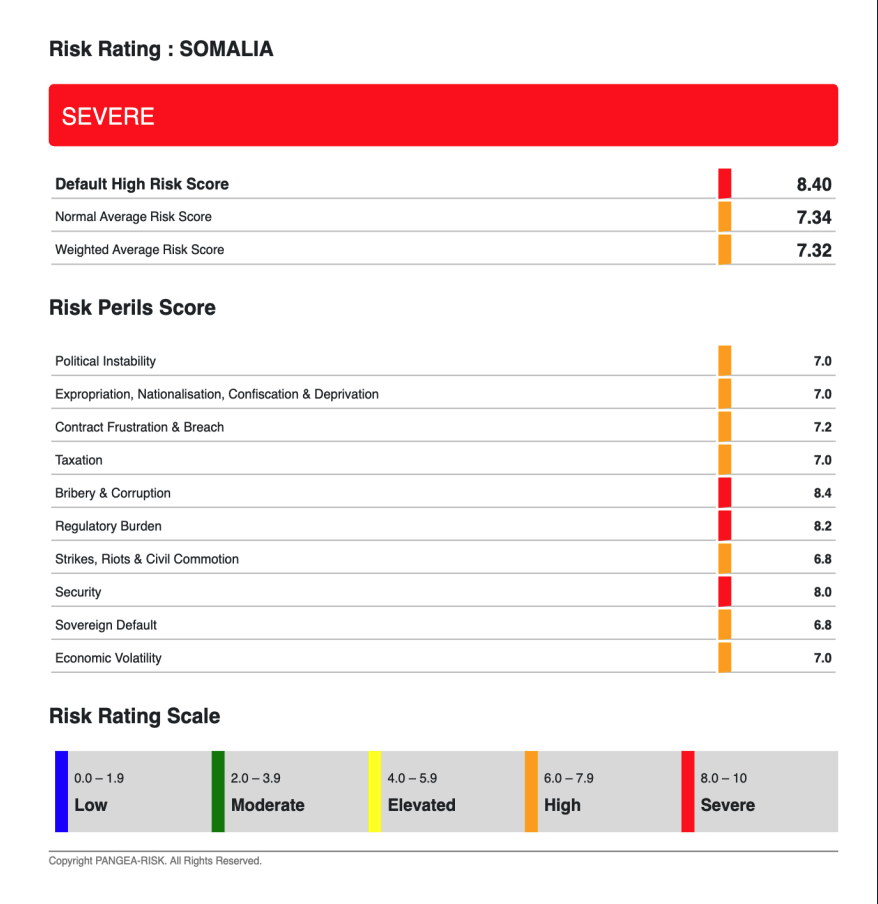

The Horn of Africa: rising instability and the resurgence of piracy

While much of the world’s attention is focused on the Strait of Hormuz, another critical region is also experiencing rising instability: the Horn of Africa. This region has long been plagued by conflict and poverty, with unstable governance pouring fuel on the flames.

For Somalia, the crisis in the Middle East is contributing to an apparent resurgence of piracy and armed robbery. Piracy off the coast of Somalia was a major international security concern in the late 2000s and early 2010s, with Somali pirates hijacking dozens of ships and demanding ransom payments that sometimes reached millions of dollars.

Now, reports assert that the Houthi rebels, who control large parts of Yemen, have been implicated in attacks on commercial vessels in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

Unconfirmed reports also point to the Houthis exploring cooperation with Al Shabaab, the Al Qaeda-affiliated militant group that controls large parts of Somalia and has also been involved in piracy. Such unrest has created a security vacuum in Somali waters, straining regional navies and contributing to the rise in pirate attacks.

Additionally, climate change has reduced fish stocks, increasing poverty and pushing more Somalis towards piracy. While Somali pirates are primarily motivated by economic gains, including ransom and control over local institutions, their objectives differ from the political and geostrategic ambitions of groups like the Houthis.

—

Any disruption to shipping in the area—whether due to piracy or regional conflict—could lead to a sharp increase in oil prices, with ripple effects throughout the global economy.

Repercussions are also severe for African states along the Red Sea, including Egypt, Eritrea, and Sudan, which have been forced to contend with reduced vessel availability, elevated freight costs, and increased insurance premiums.

The potential for these conflicts to spill over into other areas, such as North Africa or the Sahel, is a real concern, particularly given the existing security challenges in those regions.

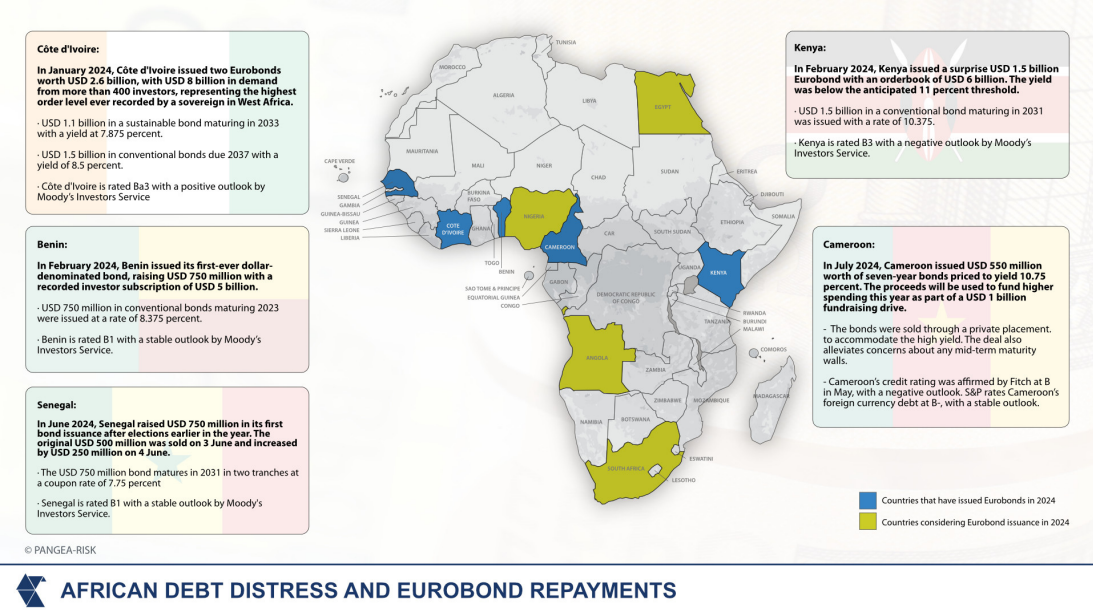

Pangea Risk July 2024 briefing

In July 2024, five African countries (Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, Kenya, Senegal, and Cameroon) returned to the Eurobond market after a two-year hiatus, raising a total of $6.2 billion, demonstrating a renewed appetite for international bonds despite existing high debt levels.

Data from the African Development Bank (AfDB) indicates that the continent’s total external debt increased from $1.12 trillion in 2022 to $1.152 trillion in 2023. This renewed borrowing spree, however, comes with challenges.

Notably, the uncertainty surrounding the upcoming US presidential election has made African treasuries cautious. Political instability in the US could impact global markets, leading African nations to hedge their bets by stockpiling gold reserves, which is seen as a strategy to safeguard against potential volatility in the bond markets.

In addition, the high cost of borrowing remains a significant hurdle. For instance, Kenya issued a Eurobond in February with a yield of 10.375%, while Cameroon issued $550 million in international bonds at an even higher yield of 10.75%. These high borrowing costs reflect the urgent need for funds but also highlight the risk of further debt accumulation.

A common thread among the countries returning to the Eurobond market is their engagement in staff-monitored programmes with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). While the IMF’s policy support has attracted investors, the stringent fiscal conditionalities attached to these programmes have created domestic challenges.

Kenya, for example, attempted to raise taxes and cut subsidies to meet IMF requirements after refinancing a $2 billion Eurobond. The resultant political upheaval in Kenya, with protests turning violent, illustrates the social tensions arising from fiscal austerity measures.

The situation in Kenya is not isolated.

Other African nations, including Nigeria and Uganda, face growing public unrest due to high living costs and fiscal consolidation efforts. Civil society groups in Nigeria are preparing for widespread protests, echoing the sentiments of the #EndSARS movement from 2020.

High food price inflation in countries like Ghana, Angola, and Ethiopia is exacerbating socio-economic tensions and may lead to more protests. Authoritarian states, such as Uganda, have also witnessed civil unrest, with protests being forcibly suppressed.

Despite the challenges, the need for sustainable debt solutions remains critical. Several African nations will face significant Eurobond maturities from 2025 onwards and require continued fiscal consolidation.

Emerging market local currency debt has been impacted globally by high US interest rates and geopolitical risks.

South Africa stands out as an exception, with its local currency bonds performing well due to a market-friendly coalition government. This presents an opportunity for commercial lenders, possibly backed by development finance institutions, to offer alternative financing options to African sovereigns.

While Africa’s return to the Eurobond market in 2024 signifies a shift for the continent, decision-makers must navigate the complexities of high borrowing costs, political uncertainty, and social unrest to ensure sustainable economic growth and stability.

Maritime Insight: Red Sea trade diversions drive fresh investment in African ports

Houthi attacks in the Western Indian Ocean and the Red Sea have significantly escalated, leading to major disruptions in maritime traffic and global trade routes. Since November 2023, over 150 attacks have been reported, prompting stakeholders to seek alternative routes around the African continent. This shift has increased demand for services at African ports, revealing infrastructural deficiencies and creating new opportunities.

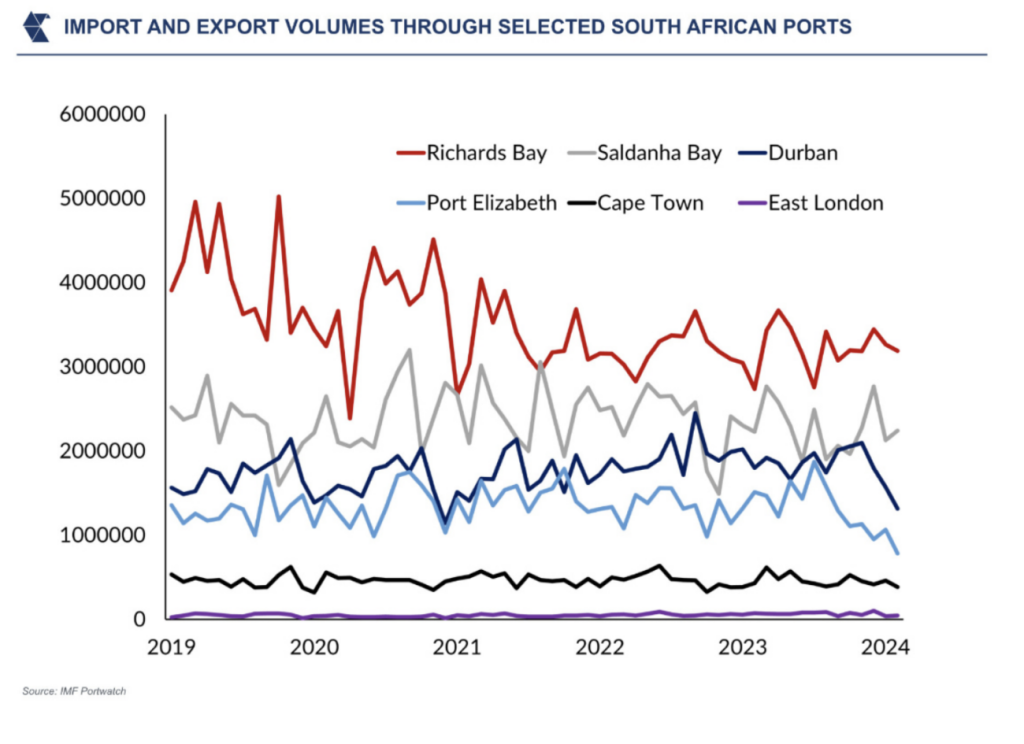

Ports in Mauritius, Madagascar, and Mozambique have strategically benefited from their locations, while South African ports struggle with outdated infrastructure and poor management. South African ports such as Durban, Port Elizabeth, and Cape Town have seen a 53% surge in maritime activity over three months, transforming them into key logistical hubs.

However, infrastructural deficiencies, including outdated equipment and lack of financial investment, have resulted in significant congestion and delays. Durban’s Pier 2 terminal has faced severe berthing delays, with backlogs escalating to crisis levels, leaving 79 vessels and over 61,000 containers at outer anchorage for weeks.

The diversion of global shipping from the Red Sea and Suez Canal has increased demand for bunkering and restocking services at African ports. This shift has exposed the inability of many African harbours to handle the increased freight volume, causing congestion and delays. Average wait times at these ports now extend beyond the global average of three days to as many as six days or more.

Djibouti, heavily reliant on its ports for revenue, has been significantly affected by the decline in shipping through the Bab Al Mandeb Strait and the Suez Canal. Despite substantial investments in port infrastructure, continuous attacks have threatened its strategic advancements. Major international shipping lines, such as Maersk, have taken precautionary measures, including avoiding bookings to Djibouti’s ports.

Elsewhere, African ports in Sudan, Eritrea, and Somaliland face challenges from reduced vessel availability, higher freight costs, and increased insurance premiums. This has adversely affected their maritime trade, reversing previous decisions to remove high-risk designations for areas like Kenya. As a result, five major carriers have withdrawn their vessels from operating in Somali and Kenyan territorial waters.

While the increased demand has highlighted the unpreparedness of African ports, it has also drawn global investors’ attention. Countries such as Tanzania, Kenya, Mozambique, and South Africa are at the forefront of port development, driven by both domestic initiatives and foreign investments. For instance, DP World plans to invest $3 billion in new port and logistics infrastructure in Africa over the next three to five years.

Mozambique’s ports have attracted substantial investments, with the port of Beira undergoing significant infrastructural improvements over the past 25 years. South Africa’s Transnet has entered a 25-year joint venture with International Container Terminal Services Inc. (ICTSI) to manage Durban’s container terminal, aiming to resolve longstanding congestion and inefficiencies.

The future of Africa’s ports sector will depend on various factors, including the extent of Houthi military operations, the capacity of African countries to advance their port infrastructure, and the international community’s response. Despite current challenges, African countries have the potential to become new hubs for global shipping, provided they can modernise and expand their port facilities.

Enhanced collaboration between African governments and international operators could improve the competitiveness of African ports, repositioning them on the global stage and providing vital logistical support to international shipping routes.

Growing demand for Africa’s critical minerals intensifies geopolitical rivalries

The global critical minerals market is adapting to heightened demand from renewable energy sectors and Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) technologies, leading to growing shifts in geopolitical dynamics. This includes major powers diversifying sources away from dominant suppliers such as China due to recent global events like the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

In response, regions rich in minerals, such as Africa and the Middle East, are becoming focal points for new mining investments and strategic partnerships. Simultaneously, the United States and European Union Countries are reformulating policies to secure and stabilise mineral supply chains, reflecting the increasing importance of these resources for future technological advancements and economic security.

As the world’s clean energy transition and Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) technologies gather pace, the demand for critical minerals is expected to grow quickly. This heightened demand places Africa’s mining sector at the centre of geopolitical competition due to its pivotal role as a supplier of many critical minerals necessary for these energy transitions.

This shift is visibly marked by the United States’ (US) renewed engagement with African producers such as Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Deposits of graphite, lithium, and rare earth elements in these regions are experiencing an upsurge in exploration activity and competition from both Chinese and Western buyers. This trend is anticipated to extend benefits not only to established producers but also to mid-tier, smaller, or less explored mining markets in countries like Côte d’Ivoire, Mozambique, and Namibia, making them increasingly attractive to investors.

Despite these opportunities, Africa’s mining industry predominantly operates on a “pitto-port” model, where mineral ores are extracted and exported for processing elsewhere. The security and reliability of these critical mineral supply chains are of strategic importance to many countries, especially in light of the expected surge in global demand driven by clean energy technologies.

Historically, concerns regarding Africa’s mining sector have revolved around fears of Chinese dominance over the production of critical minerals and, more recently, Russia’s interests in West African gold. However, companies from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), armed with substantial financial resources, have shown they can outbid more established players in the industry, as demonstrated by recent competitive activities in Zambia.

PANGEA-RISK assesses the geopolitical and economic factors influencing the global critical minerals sector, focusing on the challenges and opportunities within Africa and the Middle East and their implications for international markets and supply chains.

African sovereign debt: Stepping back from the edge

At the beginning of 2024, the outlook for African sovereign debt sustainability substantially improved, evidenced by the re-entry of several African issuers to the international bonds market. Pangea-Risk’s previous white paper on this subject, released in February 2023, suggested that numerous African sovereigns, grappling with debt sustainability issues, would have successfully restructured their most burdensome loans, thus steering these nations towards enhanced debt sustainability.

After a year marked by challenges in debt issuance, especially for frontier market participants, certain African sovereign borrowers took this chance to engage with investors outside of deal-making contexts, providing updates on their financial standings.

This approach of open and transparent communication has enabled some issuers to make a comeback to the market in 2024, with others, including potentially Angola and Nigeria, preparing to follow suit in the upcoming months.

Driven by this positive trend, many African sovereigns are emerging from the so-called “African debt crisis” and are re-establishing themselves as trustworthy borrowers, simultaneously reinforcing their status as dependable partners for trade and investment. In this 2024 white paper, Acre Impact Capital and Pangea-Risk evaluate the prospects for African sovereign debt sustainability and pinpoint fresh opportunities for trade and investment.

The white paper was authored by PANGEA-RISK and Acre Impact Capital.

Senegal’s new political leadership to face economic challenges

Senegal stands at a pivotal juncture in its political history, with the election of Bassirou Diomaye Faye as the new President, a development that has stirred both hope and apprehension among various stakeholders.

Faye, a former tax inspector and transparency activist, alongside his political mentor, Ousmane Sonko, represents a fresh but inexperienced leadership duo poised to navigate the complex waters of Senegal’s economic and political landscape.

Massive UAE investment into Egypt bolsters forex reserves and catalyses enlarged IMF deal

In February 2024, Egypt secured a monumental investment deal with an Emirati sovereign wealth fund, amounting to $35 billion. This substantial agreement, centred on the ambitious development of Ras El Hekma city, marks a significant milestone in Egypt’s efforts to fortify its economic foundations.

While the investment is expected to enhance Egypt’s foreign exchange reserves and provide a much-needed impetus to the country’s economy, it also brings into focus the pressing need for comprehensive structural reforms to ensure long-term sustainability and growth.

Pangea-Risk launches climate insights

Maritime Insights: US-led airstrikes will not curb Houthi threat in Red Sea

The escalation in the Red Sea, marked by US-led airstrikes against Houthi forces in Yemen, highlights the complexities of maintaining maritime security in this vital region. Despite the strategic targeting of more than 60 Houthi positions by the United States and its allies, the impact on curtailing Houthi maritime aggression appears limited.

Africa in 2024: Identifying major country risk trends, opportunities and hotspots

Africa in 2024 stands at the crossroads of unprecedented economic growth and daunting challenges. As the continent positions itself as a pivotal player in global economic expansion, it grapples with enduring vulnerabilities to climate change, food insecurity, foreign exchange shortages, and political instability.

The dichotomy of Africa’s trajectory is marked by its potential to drive trade and investment, juxtaposed against the backdrop of regional conflicts and debt vulnerabilities that may be exacerbated in the coming year.