- US President Donald Trump has announced a 25% tariffs on imports from Canada and Mexico, to which Canada has retaliated with a 25% tariff.

- The US has also placed a 10% tariff on Chinese imports, mediating from the promised 60% figure.

- Trump has warned of similar measures for the EU.

Some speculated, and others hoped, that Donald Trump’s promises of brutal tariffs were merely an election-winning tactic to frenzy his domestic fanbase. But on 1 February 2025, less than two weeks into his presidency, it transpired that Trump was being serious. Executive orders signed on Saturday imposed a 25% tariff on imports from Canada and Mexico and a 10% levy on goods from China. These tariffs will take effect from tomorrow, 4 February.

On Sunday night, 2 February, Trump promised that tariffs on the European Union (EU) would “definitely happen” and “it’s going to be pretty soon.”

Trump posted this executive order by invoking the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), which grants the president authority to regulate international commerce in response to a declared ‘national emergency’.

IEEPA was first used by then-President Jimmy Carter in 1977, in response to the Iran hostage crisis. During his first term, Trump threatened to impose tariffs on Mexico in response to the “illegal migration crisis”, which he backed down from in June 2019, but he did use the IEEPA against Venezuela and Iran.

This time, Trump said the flow of “illegal aliens and drugs” – referring to 21,000 pounds of fentanyl apprehended by the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) in the last fiscal year, and “more than 10 million” illegal immigrants entering the US under Biden – constitutes a national emergency. But the sanctions are incommensurate with the crime, particularly on its northern border, through which less than 1% of illegal immigrants entered the US, and where just around 1% of the US’ fentanyl encounters take place.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has already imposed a 25% reciprocal tariff on American goods, and Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, ministers across EU countries, and China have all vowed retaliation. “It’s important that we don’t divide the world with numerous tariff barriers,” said German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, promising a collective response. “[The EU is] a strong economic area and has its own courses of action.”

Trump admitted on Sunday that there may be “some pain” from his tariffs, “but […] it will all be worth the price that must be paid.” Trade wars rarely have victors, but those who suffer the most are invariably the poorest.

The North American retaliation

Sheinbaum “categorically reject[ed]” Trump’s assertions in his IEEPA declaration, pointing out that the Mexican government has “seized more than 40 tons of drugs in four months, including 20 million doses of fentanyl”, and “arrested more than ten thousand people linked to these groups”.

Sheinbaum said, “I instruct the Secretary of Economy to implement plan B that we have been working on, which includes tariff and non-tariff measures in defence of Mexico’s interests.”

Retaliatory tariffs in the USMCA region is no new phenomenon. The softwood lumber dispute between the US and Canada lasted from 1982 to 2014, and is based on the countervailing duties (CVDs) placed by the US on imports of this wood to Canada; the British Columbia region reported the loss of nearly 10,000 jobs as a result between 2004 and 2009.

This time around, Trudeau has targeted American alcohol, fruits and vegetables, household appliances, and clothing items.

The US has decided to impose a reduced 10% tariff on Canadian energy imports, rather than the full 25% rate, designed to help limit potential increases in consumer energy costs. Despite this measure, analysts project that US consumers could still face fuel price increases of up to 50 cents per gallon. Simultaneously, the automotive industry will also likely take a hit, considering that about 50% of auto-part imports in America come from Canada and Mexico, and about 75% of American exports go to its neighbours.

Nonetheless, Canada and Mexico are heavily dependent on the US market: Canada sends 78% of its annual exports ($567 billion), and Mexico 80% ($593 billion), to the US. However, the US maintains a more diversified import portfolio – of its $3.17 trillion in annual imports, only about 14% comes from Canada and 15% from Mexico. This imbalance may give the US more flexibility in its trade options and potentially stronger negotiating power with its North American neighbours. Already, in currency markets, the Mexican peso fell by almost 3%, and the Canadian dollar hit its lowest level since 2003.

China countermeasures

Similarly, while retaliatory tariffs are a common feature of US-China trade relations, they have never been this severe. During Trump’s first term, $370 billion worth of Chinese imports were affected by tariffs, a figure set to increase with the additional 10% rate. But this differed from the 60% he touted on the campaign trail—probably because the Chinese capacity for retaliatory tariffs poses a significant threat.

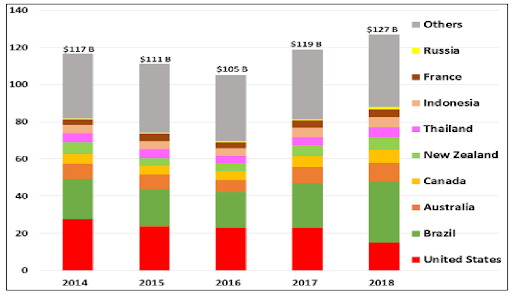

An interesting feature of Chinese retaliatory tariffs is their targetedness, as we are now seeing in Canada. In 2018, Trump announced tariffs of 25% on steel and 10% on aluminium imports from China; in response, China levied a series of 15% to 25% tariffs on agricultural imports. By 1 September 2019, the number of US agricultural tariff lines with Chinese retaliatory tariffs increased to 1,053.

This move was strategically against American farmers (a key demographic of Trump voters). In the short run, the downward pressure on US farm incomes triggered ‘trade aid’, federal assistance for the sector. And trade networks meandered around obstacles, as China began to rely on other southern allies for agricultural products, from soybean and pork to cotton and tobacco.

China’s Imports of Agricultural Products, 2014-2018, in Nominal Billions (B) of US Dollars. Source: Congressional Research Service

Today’s macroeconomic landscape mirrors this but renders it much sharper. China’s Belt and Road Initiative, a series of urbanising initiatives across the developing world, has tied the country to the fortunes of these nascent trading hubs. The South-South rerouting is underway; this time, retaliatory tariffs may even cut the US out of the equation altogether.

—

Mark Carney, former Governor of both the Bank of Canada and the Bank of England, warned that the proposed tariffs would hamper economic growth while stoking inflation. “They’re going to damage the US’s reputation around the world,” said Carney, who is currently among the contenders to succeed Trudeau as leader of Canada’s Liberal Party.

The UK’s Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer and Foreign Secretary David Lammy are modulating their stance to shield the UK from such measures. For now, Trump has said of Starmer that “we’re getting along very well, we’ll see whether or not we can balance out our budget”. Chris Southworth of the International Chamber of Commerce UK said on LBC Radio that the UK could serve as a “pragmatic bridge”, a broker of conversation between the US and Europe. But complacency is a weakness when dealing with someone so volatile and impulsive.

Is this just a calculated move to demonstrate resolve? If so, it’s a risky gambit that could destabilise the global economy. But the US would do well to consider how many opponents it can afford to make because if the world of trade and trade finance is anything, it is malleable.