On the 15th November, 2020 several Heads of State/ Government of the Member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and other nations met virtually to witness the signing of The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement – solidifying over 8 years of negotiations and challenges.

“We were pleased to witness the signing of the RCEP Agreement, which comes at a time when the world is confronted with the unprecedented challenge brought about by the Coronavirus Disease 2019”

RCEP, in it’s initial and current capacity spans across the below 15 nations, which combined include 2.2 billion people (almost 30% of the world’s population), a collective GDP of US$ 26.2 trillion – 30% of global GDP and almost 28% of global trade, according to the Joint Leader’s Statement

Members:

- Brunei Darussalam (population of 437k)

- Cambodia (population of 16.25m)

- Indonesia (population of 267.7m)

- Lao PDR (population of 7m)

- Malaysia (population of 31.5m)

- Myanmar (population of 53.7m)

- The Philippines (population of 106.7m)

- Singapore (population of 5.6m)

- Thailand (population of 69.4m)

- Vietnam (population of 95.5m)

- Australia (population of 24.9m)

- China (population of 1.4bn)

- Japan (population of 126.5m)

- Korea (population of 51.6m)

- New Zealand (population of 4.8m)

At its core, the RCEP agreement aims to strengthen regional supply chains, support economic recovery amid the Covid-19 pandemic, promote job creation and lay the ground work for an “open, inclusive, rules-based trade and investment arrangement”. It will do this through multiple channels, but most notably the elimination of tariffs and quotas in over 65% of goods traded between the member states.

The agreement itself has 20 chapters (explored later) which cover a vast range of topics, from Customs Procedures and Trade Facilitation to Intellectual Property and E-commerce. However, the addition of a new ‘Rule of Origin’ may be the most beneficial element of RCEP for it’s members.

Currently, there are of course existing Free Trade Agreements (FTA’s) between some (now) RCEP members in various combinations (AJCEP, AIFTA etc.). However, because these FTA’s are specific to certain nations and not all encompassing, certain trades with goods originating in countries not aligned to an FTA still face tariffs and other trade limitations.

With RCEP operational, all goods from any member state will be treated equally, providing incentive for suppliers in these nations to look inward to RCEP members for trade, further promoting the trade within the geographic outlined in the agreement.

There will be a new “RCEP certification of origin”, that will verify a good’s origin is indeed within the RCEP market, and so the treatment of this good in relation to tariffs/ procedures would be more favourable against those without said certification. As reads ASEAN’s official summary of the agreement:

“Section B: Operational Certification Procedures provides detailed procedures for applying the RCEP proof of origin, claiming preferential tariff treatment, and verifying the originating status of a good.”

Origin Story

During the 21st ASEAN summit in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2012, 16 Economic Ministers officially endorsed the “Guiding Principles and Objectives for Negotiating the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership”, which recognised the need to achieve a modern, comprehensive, high-quality and mutually beneficial economic partnership between ASEAN members and FTA partners of ASEAN.

According to New Zealand’s Foreign Affairs and Trade Manatū Aorere, since those endorsements in 2012, RCEP countries have participated in 31 rounds of negotiations, various Ministerial meetings and 3 Leaders Summits, with the first round being held in Brunei following the 21st Summit in Cambodia.

One nation did not make the 8-year marathon from that first round in 2013 to RCEP’s Signing Ceremony in 2020 – India. Following 28 rounds of negotiations, India chose to drop out of the agreement in November 2019. Citing many ‘outstanding and unresolved issues’, India had concerns that participation in the agreement could potentially lead to a flurry of cheap Chinese goods into India’s consumer market, damaging domestic producers.

In a RCEP Summit in Bangkok in October of 2019, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi told Leaders and Government Representatives “The present form of the RCEP Agreement does not fully reflect the basic spirit and the agreed guiding principles of RCEP. It also does not address satisfactorily India’s outstanding issues and concerns”.

However, the official agreement signed and celebrated on the 15th November does include capacity to absorb India into the economic partnership at a later date, following the resolution of the ‘outstanding issues’. In the most recent Joint Leader’s Statement, India’s inclusion is recognised to be of significant importance in achieving the partnership’s mission of “even deeper and expanded value chains for the benefit of all people in the [RCEP] region”.

![[RCEP] region](https://www.tradefinanceglobal.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/923634-india-china-conflict.jpg)

India, being a market of 1.53 billion people, with a GDP of US$ 2.9 trillion in 2019 and exporting $536bn of goods and services in 2019, would clearly be a substantial addition to the economic agreement. As such, the RCEP signing statement included 3 key acknowledgements and confirmations that not only allows for their physical inclusion in the agreement at a later date, but allows them to be included in any discussions/ economic cooperation activities as an ‘observer’ until the date in which they sign:

1) The RCEP Agreement is open for accession by India from the date of entry into force of the Agreement as provided in Article 20.9 (Accession) of the RCEP Agreement;

2) The RCEP Signatory States will commence negotiations with India at any time after the signing of the RCEP Agreement once India submits a request in writing of its intention to accede to the RCEP Agreement to the Depositary of the RCEP Agreement, taking into consideration the latest status of India’s participation in the RCEP negotiations and any new development thereafter; and

3) Any time prior to its accession to the Agreement, India may participate in RCEP meetings as an observer and in economic cooperation activities undertaken by the RCEP Signatory States under the RCEP Agreement, on terms and conditions to be jointly decided upon by the RCEP Signatory States.

Power of RCEP

As previously mentioned, this economic agreement covers a significant proportion of the global population, global GDP and global trade.

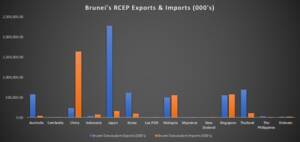

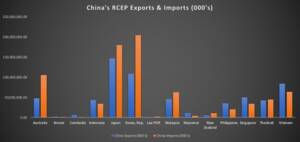

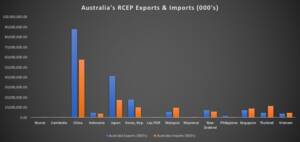

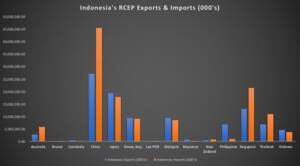

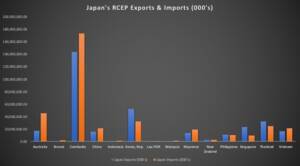

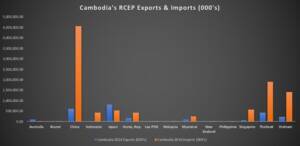

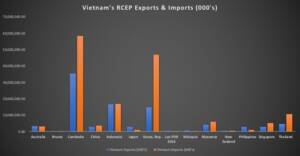

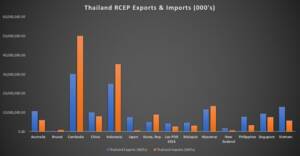

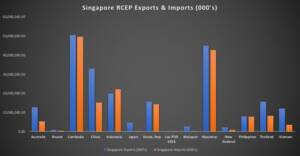

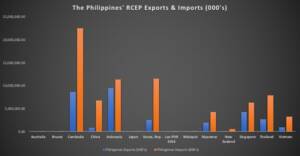

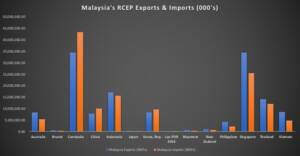

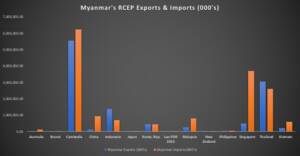

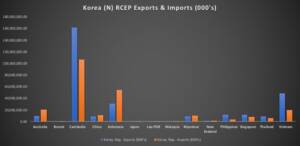

Below, using the most recent data from WorldBank, Trade Finance Global have visualised each member’s Exports vs. Imports with other member nations. It is worth noting the aforementioned elimination of tariffs on some c.65% of goods traded between these parties:

As shown in the above visuals, not only do the current 15 members of RCEP account for just under 30% of global trade, a significant amount of that trade already takes place between them. If we now recall the Rule of Origin rule introduced in the agreement, alongside the elimination of tariffs on up to 65% of goods traded, we can clearly see the value this partnership brings. If we then include India, the worlds 5th largest economy as of 2019, the RCEP inflates furthermore as the world’s largest trade agreement.

The rule of origin clause and tariff elimination are not the only principles underpinning the RCEP. Below, we see the titles of each of the 20 chapters included in the signed edition of the agreement as aligned in ASEAN’s official summary:

- Initial Provisions and General Definitions

- Trade in Goods

- Rules of Origin

- Customs Procedures and Trade Facilitation

- Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS)

- Standards, Technical Regulations, and Conformity Assessment Procedures (STRACAP)

- Trade Remedies

- Trade in Services

- Temporary Movement of Natural Persons (MNP)

- Investment

- Intellectual Property

- Electronic Commerce

- Competition

- Small and Medium Enterprises

- Economic and Technical Cooperation (ECOTECH)

- Government Procurement

- General Provisions and Exceptions

- Institutional Provisions

- Dispute Settlement

- Final Provisions

As these chapter titles show, there is a broad width of activity that is now governed in the RCEP agreement. Outside of the preferential treatment of goods dependent on the origin of the good, another significant offering of the agreement would be Chapter 14: Small and Medium Enterprises – this chapter illustrates the recognition of SME’s ‘significant’ contribution to economic growth, employment and innovation. Because of this, the agreement sets a foundation for member parties to promote and share RCEP-related information that would be relevant to SMEs, through the provision of a publicly accessible information platform.

The Right Place in Time

Although the journey of RCEP began 12 years ago, the completion of the agreement in November 2020 is a potential glimmer of hope for the regions that have signed, which, similar to all other nations in the world have seen significant difficulty throughout the year due to Covid-19. The ASEAN-5 (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand) alone have seen their real GDP decline by -3.4% as of October, according to the IMF.

Providing a trading platform that is as progressive as the RCEP agreement whilst the world is almost a year into the pandemic will likely prove integral to the economic recovery of these economies. Interestingly, some Southeast Asian nations such as China and Korea have struggled less economically than other nations around the world, with early and strict lockdowns claiming much of the credit for ‘curbing the spread’.

This being said, whether or not the macroeconomic indicators of RCEP members are more beneficial than other nations, the impact on global supply chains is present nonetheless, and so the creation of a trading agreement that promotes trade within the geographic will provide trading avenues that have, up until now not been viable – financially or otherwise. This will

inevitably increase the efficiency of economic recovery for the signing members of RCEP.