Sustainability is no longer an adjunct to good business, but pivotal to it. TFG heard from Standard Chartered Bank, on the difficulties that many multinational corporations (MNCs) face in terms of delivering the UN SDGs in practice.

Sustainability is no longer an adjunct to good business, but pivotal to it. In August 2019, the United States Business Roundtable, an association comprising CEOs of leading US corporations that together employ 15 million people and generate $7 trillion in annual revenues, globally committed to placing sustainability and fair, ethical engagement with suppliers at the heart of business practice. The difficulty for many multinational corporations (MNCs), is how to deliver on this objective in practice.

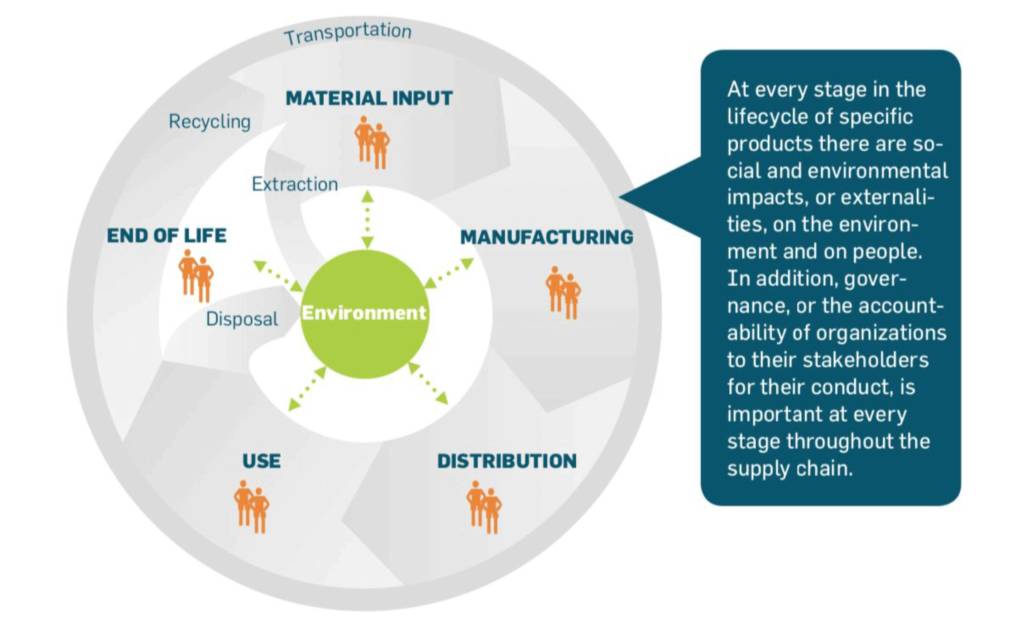

Large multinational corporations (MNCs) play a vital role in achieving the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, a key theme of this year’s World Economic Forum. Global supply chains extend into many of the regions and communities that are most vulnerable to negative environmental and social impacts that can result from every stage of the supply chain (figure 1) so reducing these effects is critical to building sustainable and secure environments, communities and supply chains. Stakeholder scrutiny is also growing amongst investors, employees and customers, increasing the pressure on businesses globally to demonstrate sustainable business practices.

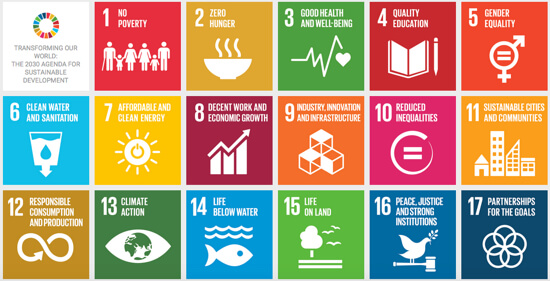

One challenge for MNCs in developing sustainable supply chains is how to define ‘sustainable’. Complying with the United Nations’ seventeen Sustainable Development Goals, together with the UN Global Compact’s ten principles for sustainable supply chains, means that corporations need to measure a large number of metrics. Realistically, they need to prioritise, at least initially, and are most likely to focus on measures where regulations exist, such as anti-slavery rules, and issues on which their stakeholders are most engaged.

Responding to the climate challenge

Climate change, for example, has become one of the biggest investor and consumer concerns, and is at the heart of sustainability ambitions at a global, national and local level. Eighty five percent of Britons are concerned about climate change, with the majority (52 percent) very concerned. In Singapore, this figure is over 90 percent. Almost half of Europeans identified climate change as a greater threat to their lives above unemployment, large scale migration and terrorism.

Despite growing public awareness and concern, and the EU declaring a climate emergency in November 2019, businesses are not yet doing enough. Mark Carney, outgoing governor of the Bank of England and newly appointed UN Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance described the situation as “the catastrophic business as usual scenario”. He warned, “Those that fail to adapt will cease to exist. The longer that meaningful adjustment is delayed, the greater the disruption will be.”

There are ‘green shoots’ with large corporations making bold commitments to reducing or removing their environmental footprint. In January 2020, Microsoft’s President Brad Smith commits,

“By 2030 Microsoft will be carbon negative, and by 2050 Microsoft will remove from the environment all the carbon the company has emitted either directly or by electrical consumption since it was founded in 1975.”

This commitment relies not only Microsoft’s internal efforts, but also wider initiatives across its supply chain. The company is launching initiatives to help customers and suppliers reduce their carbon footprints, and a new $1 billion carbon innovation fund. From 2021, carbon reduction will be an explicit aspect of its supplier procurement processes.

A sustainability stalemate?

Building sustainable supply chains is not easy in practice, however, and arguably, some current initiatives may have the opposite effect. For example, some leading MNCs and their banking partners are incentivising suppliers to adhere to sustainable principles by offering preferential supplier financing rates. This approach is unsustainable, however, as the cost of financing a sustainable vs. unsustainable supplier is the same, ultimately eroding margins which will reduce the incentive for banks to offer financing. The onus on banks to validate a supplier’s credentials creates further cost. Although unintended, the result is that it ultimately becomes more profitable to work with unsustainable suppliers.

There has been a number of early experiments and partnerships, such as Project Trado, to increase transparency and sustainability across supply chains. Although encouraging, a more extensive and far-reaching approach will be required to build the sustainable supply chains of the future. The incentives for doing so are significant. As Standard Chartered’s recent Opportunity2030 report illustrates, there are investment opportunities of almost USD10 trillion (USD9.668 trillion) across emerging markets to help achieve the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These markets are increasingly important to global supply chains but have the least ability to invest in tackling climate change and other sustainability objectives. In the coming months, we see a growing demand and opportunity for innovative solutions that deliver sustainable finance at a lower cost with better returns, therefore incentivising all supply chain participants, including financiers, to help break through the sustainability obstacles that we all face.

Now launched! Spring Edition 2020

Trade Finance Global’s latest edition of Trade Finance Talks is now out, taking a deep dive into trade finance in emerging and developing markets.