Estimated reading time: 0 minutes

Sanctions and frosty trade relations have been a consistent theme of international trade in the past half-decade, but even more so after the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022.

Since then, Western governments have attempted to curtail direct and indirect trade with Russia, both to impose economic punishment and diminish Russia’s ability to produce military equipment.

However, the world of international trade is often quite opaque, and while governments can introduce sanctions, their effectiveness is not guaranteed.

To discuss S&P Global Market Intelligence’s whitepaper, “Are transshipment hubs facilitating the movement of Western-made components to Russia?” Trade Finance Global’s Deepesh Patel spoke with Ravi Amin, Trade Compliance Subject Matter Expert, at S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Effectiveness and evasion of sanctions on Russia

Since early 2022, Western governments have imposed numerous rounds of sanctions on Russian economic activity.

As of June 2024, the EU alone has implemented 14 rounds of sanctions against Russia since their invasion of Ukraine.

Amin said, “The idea is to restrict Russia’s economy, stop them from exporting goods and making money, and then stop the import of goods into Russia to stop the perforation of their war efforts.”

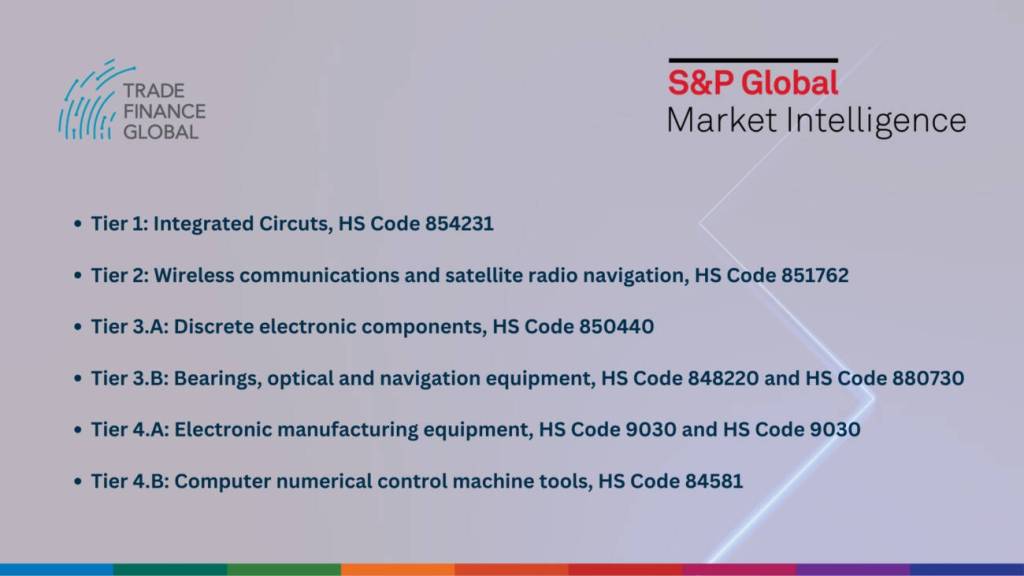

Initially, the focus was on items directly supporting Russia’s military, such as semiconductors and electronics, but eventually expanded to include civilian luxury goods.

The items were divided into different tiers, ranging from 1-4b, which essentially was an augmentation of 50 HS codes.

HS Codes, “Harmonized System codes”, are the six-digit numbers used internationally to classify goods for customs purposes.

Administered by the World Customs Organization (WCO), they cover 98% of goods in international trade and over 5,000 commodities.

Customs authorities use HS codes to apply tariffs and taxes to goods and keep track of imports and exports.

Despite these extensive measures to sanction materials based on their HS codes and different tiers, Russia has been able to work around some of the sanctions, maintaining a relatively stable trade profile.

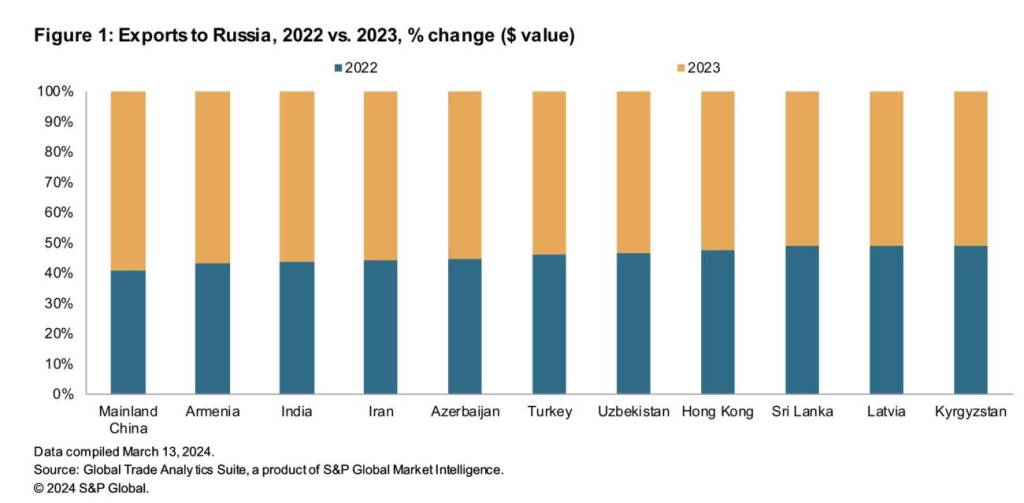

Amin said, “They’ve redirected their exports to countries in Asia and are importing goods from neighbouring countries that haven’t imposed sanctions. Overall, the trade profile is relatively consistent pre-invasion versus post-invasion; they’ve just used different countries to acquire or sell those goods.”

Neighbouring countries—particularly those within the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), such as Kazakhstan, Armenia, and Uzbekistan—have significantly increased their trade with Russia.

These countries are not only relying on goods from the United States either, though a significant amount of the imports do stem from there.

Countries that have increased trade with Russia since the invasion have also been increasing their imports from the EU.

Amin said, “Russia’s trading partners are potentially importing materials from other countries as well within Europe.”

This underscores a critical challenge: while sanctions disrupt direct trade channels, they often fail to eliminate economic interactions entirely and merely displace trade flows to other willing partners.

The data from S&P Global Market Intelligence corroborates this adaptive behaviour.

It shows that countries without sanctions on Russia have seen increased imports of goods that could be repurposed for military use. This trend is particularly notable in the electronics and manufacturing sectors, where goods initially intended for civilian use in intermediary countries are subsequently funnelled into Russia.

Role of financial institutions and the supply chain in compliance

The responsibility for enforcing sanctions extends beyond government agencies, deeply involving financial institutions and the broader supply chain.

Amin said, “There has been a lot of focus on financial institutions from multiple regulators around the world in the past. Primarily, the onus has on them to stop the flow of sanctioned goods, and they would have had to adapt their compliance procedures to incorporate any changes.”

This involves a comprehensive review of trade embargoes, export controls, and tracking goods that may have military applications.

For instance, banks must perform enhanced due diligence if a trade transaction involves a country identified as a trans-shipment hub for Russian goods.

Amin said, “If there is a trade that is going from, say, the US to, say, Kazakhstan, for example, you now know that there is elevated risk based on the proximity of Kazakhstan to Russia, based on the data that we’ve just shown. Even though Kazakhstan is not a sanctioned country, why is that company now wanting to trade with Kazakhstan where previously they might not have? Does the trade make economic sense?”

Under USA Executive Order 14114, the scope of these sanctions is no longer limited to financial institutions in the United States. The order, signed by US President Joe Biden in December 2023, expands the ability to impose sanctions on foreign financial institutions engaging in transactions involving Russia’s military-industrial base.

While the burden has traditionally sat with financial institutions, entities across the entire supply chain now have an increasing role to play in maintaining compliance.

The USA has also imposed a Quint-Seal Notice, which mandates that all parties involved in the trade process—from financiers to shippers—must ensure that the goods being traded do not contravene international sanctions.

Amin said, “It’s no longer just the financial institution that’s responsible, it’s everybody.”

Future projections and stricter sanctions

Looking ahead, the landscape of sanctions against Russia is poised to become even more stringent.

Amin said, “As long as the conflict continues, sanctions will continue. What will end up happening is they’ll start targeting new sectors of the Russian economy. They’ve already done agriculture to a degree, sanctioning fertilisers, timber, and the like. They’ve already targeted transport. They’ve already targeted defence. They’ll find new ways, new items to sanction Russia with until the conflict ends.”

In early 2024, the United States announced a new round of over 500 sanctions, targeting card payment systems, military institutions and financial institutions. After this round, the United States has sanctioned over 4,000 entities connected with Russia since the start of the invasion.

Additionally, the 14th round of sanctions by the EU targets sectors like liquefied natural gas (LNG) and imposes stricter controls on vessels historically linked to Russian ports.

The international community remains steadfast in its efforts to curtail Russia’s economic and military capabilities through increasingly sophisticated and targeted measures.

While these measures have undoubtedly disrupted direct trade channels, Russia’s strategic redirection of trade highlights the challenges of enforcing a comprehensive sanctions regime. As sanctions become more stringent and expansive, the need for coordinated efforts across all levels of trade and finance becomes paramount.