Listen to this podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Podbean, Podtail, ListenNotes, TuneIn, PodChaser

Season 1, Episode 6

Host: Deepesh Patel, Editor, Trade Finance Global

Featuring: Lionel Taylor & John Bugeja, Trade Advisory Network

Turning trade tensions into opportunities – Tariffs, Education & 3D Printing – An Interview with Trade Advisory Network’s Lionel Taylor and John Bugeja

Deepesh Patel: I’m Deepesh Patel, Editor at Trade Finance Global.

We’re here, live from the ICC Banking Commission’s Annual Meeting in Beijing, with Lionel Taylor and John Bugeja, the founders and managing directors of Trade Advisory Network.

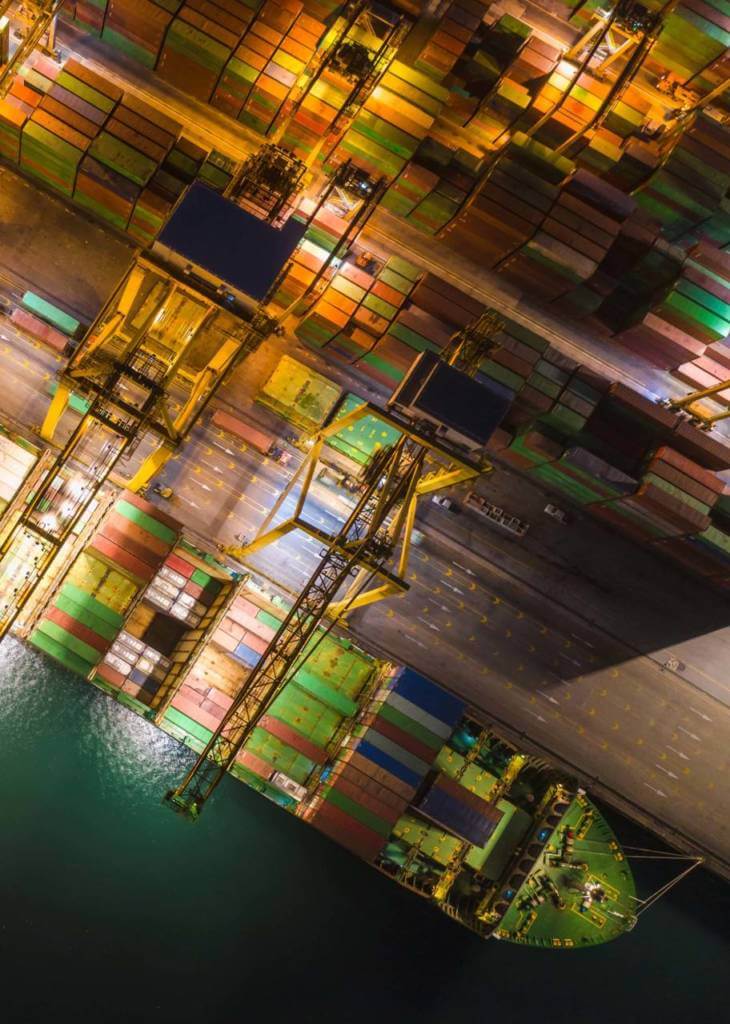

International trade continues to gain more headlines than ever before, with a fast-moving and increasingly complex global environment posing a range of challenges, from increasing concerns over protectionism and trade

In this podcast, I’m talking to Lionel and John about the impact of trade wars on the financing of international trade.

Lionel is a trade, supply chain and invoice finance business leader, with experience spanning several major financial institutions. Having co-authored qualifications for both the ICC Academy, as well as the London Institute of Banking, Lionel has extensive international experience with a specific understanding of Asia and China.

John Bugeja is an experienced trade, supply chain and invoice finance specialist too, with more than 40 years’ experience in senior leadership roles. John has several areas of expertise including origination, risk and governance, product management and development.

John is chairing a panel at the ICC Banking Commission Annual Meeting here in Beijing, on where trade tensions leave the market, and we are talking about some of the most pertinent problems these are creating within the international trade finance community.[

So, without further ado, here are Lionel and John, joining us from Beijing! Hi both, thank you so much for joining us on today’s podcast!

Lionel Taylor: Hello Deepesh.

John Bugeja: Good afternoon.

DP: So, John, over to you, in no more than 30 seconds, what does Trade Advisory Network do?

JB: We work with banks,

We work with investors who are looking to invest in

DP: Let’s jump straight into the theme of this podcast, Lionel what geopolitical and macroeconomic events today are affecting trade and trade finance?

LT: Well, obviously, we’re sitting here in Beijing, so I think a good place to start is with China. Initially, most people will look at the trade tensions between the US and China, and the challenges of tariffs and all of that. That’s obviously one of the major events that’s happening and affecting the world of trade, as is the slowdown in factory output in China. There’s a saying that when the largest economies catch a cold, the rest of the world catches pneumonia, and there is currently a fear that as China is suffering, the world as a whole will suffer as well. So obviously, the trade tensions between US and China are not helping.

Being a Brit, I think when you move across the globe we have to talk about Brexit. There’s so much uncertainty as to what’s happening with the UK, and that’s affecting the whole of the European Union. So there are a number of situations happening in the world, which affect trade. There’s also been some disturbances in the Middle East which unfortunately, again, affect the world of trade.

DP: Continuing on from this John, how serious a threat does protectionism pose to the future of trade, and what are the key issues this is having on global trade?

JB: I think protectionism has a negative effect on everyone. When a country imposes or threatens to impose import tariffs to try and protect their own industry, the effect is often to damage that country even more harshly than the countries that they’re trying to protect against. Take the situation in the States, for example. According to economists, Trump’s policies have done more damage to the US economy than the Chinese economy. So nobody really wins when you have rampant protectionism. I think the other effect of protectionism is that the companies that are involved in trade can generally fall into two categories. You have the large global corporates with lots of negotiating power and lots of options, and then you have the smaller companies who don’t have those negotiating skills or opportunities.

The large corporates can start adjusting their supply chain by regionalising their supply chain and then, over time, they can move

We interviewed Lesley Batchelor OBE, on the impact of trade tariffs on UK exporters – listen to the podcast here.

As soon as you start shifting physical supply chains, one of the consequences may well be that you have a more extended trade cycle. You’re carrying more stock and ordering from further afield if you’re trying to avoid a particular market. All of that translates into a higher working capital requirement. Now the largest global corporates have all got lots of ways of funding working capital requirements. One is trade finance and supply chain finance, but they can raise finance in any number of ways, as they have very good negotiating positions relative to the other parties in the supply chain, whether that be their suppliers or their buyers. They can push the problem of financing the increased working capital requirement either upstream or downstream, usually to smaller companies, and the smaller companies then struggle to raise the finance. So these are the consequences over the long haul.

But things will tend to stabilise and new supply chains will evolve which will level out. Technology will play a part as we see a rise in automation, so there is less dependence on manual labour which means low labour cost economies. Ultimately, this will mean you can move

That’s still a very small percentage of global trade. But that technology is getting better. And one school of thought is that will take up a lot of the slack. The jury’s out as to whether that will actually happen and there are a large number of people who don’t believe that will happen, but I think we’re all already seeing some signs of that happening.

DP: I was reading an article recently about 3D printing for construction materials and how that suddenly has a very big impact on trade flows. But I guess you’re right – as a result of protectionism and various movements, their suppliers, traders, producers are looking at changing their trade flows to things like near shore.

JB: Yes, absolutely.

DP: Lionel, in the face of trade tensions, what are the main challenges for banks, financiers, corporates, and also SMEs?

LT: Funders are not immune to the problems that are happening in the world of trade. If you’re looking at Brexit for example, and how the banks are deciding what to do – whether to stay or move to the EU – well, as the trade flows change and the way trading is undertaken changes, the banks need to adapt.

When companies in China are moving towards Vietnam, that has an effect on the local suppliers. They need new facilities to support their selling into these big corporates, and the banks are not necessarily equipped to support them. So there are challenges and sometimes these major corporates look to their global banks with payables finance type programs, and say, we’re now sourcing more from Vietnam, or from Thailand, or wherever and we need you to extend the programs into those countries. Those banks are not necessarily well equipped to actually provide these services. So you do have a challenge as a bank. When your major corporate shifts – how do you cope with that shift? No major bank likes to admit that they cannot cope, and they’re not equipped to meet that challenge, but there is a challenge with your major corporate clients, to keep your share of the wallet.

As John mentioned before, when you’re an SME looking for funding, if you’re an SME on the ground, certainly in the country that’s become in vogue, yet your banking system is not as equipped to fund working capital, you have a challenge. If you’re a small company, who is importing as well as exporting, and your trade cycle lengthens, then you’re having to either carry more cost and more working capital through your operations – so you often knock on the door of your banks, asking for help. It has been reported that there is a $1.5 trillion gap in financing for small businesses. So we are seeing challenges generally in the market, not necessarily just caused by the fact of the protectionism, and some of the stuff that’s going on around tariffs, but the banks themselves have had problems since the financial crash around increased regulation, capital requirements, and the need to decide internally, who are we and what we do we want to be? That’s often been at the cost of the smaller businesses, which is what’s creating the opportunity, allegedly, for the non-bank funders to come in and try and cover the areas that the main banks are not currently covering or do not wish to cater for.

DP: Thanks, Lionel, and we’ll come back to that a little bit later when we talk about the financing of trade and how that’s changed.

John, following on from this, what sectors are impacted the most from trade wars and trade tensions? Is it high margin or low margin products?

JB: I think any supply chain which is complex is going to be most affected by the trade tariffs and protectionism. If we take the automotive sector, for example, then you have multi-tier suppliers. So, the manufacturers may be sitting in Europe or North America or Japan, but the supply chain is pretty global. The engineering may take place in the UK, the components might be built in South Korea, even though the final manufacturing of cars is taking place in Germany. So you’ve got value add components taking place on a cross-border basis multiple times before the final finished product rolls off the production line and is then distributed through to retailers. There are lots of opportunities for trade tariffs to get in the way.

Those sorts of industries have high-worth capital goods which are expensive, so stockholder inventory finance is a big issue. The more complex the supply chain, the greater the build-up of inventory, and nobody ever wants to hold the inventory on their balance sheets. So it’s usually one of the weaker parties in the supply chain that ends up holding the

Take Apple iPhones, for example – the number of suppliers that provide components is phenomenally high. And it covers a lot of countries just to have one phone; there’s a lot of components from large parts of the world, the imposition of tariffs causes cost and friction. And they can’t quickly and easily switch suppliers because they have to be approved, they have to produce to a spec that is agreed,

Retailing is where the rubber hits the road, if you like, in terms of consumer goods. And retailing is a notoriously difficult, volatile sector in most markets. The impact of tariffs might not be immediately evident, but it works its way through the system. And it ends up with the consumer. I think the same will be said of pharmaceuticals which have to be licensed and pass certain tests. If tariffs are introduced, or non-tariff barriers are introduced, which are even more insidious in a sense, because they’re less visible, it just makes it harder for the goods to cross borders, even though there isn’t a tariff increase, that can cause a disruption to supply in a big way. And it might just be one element in a final product, which is a treatment for an illness perhaps. And if that one product is missing from the supply chain, the whole production stops or slows down. That has quite far-reaching effects at an individual level, not just at an industry level. I think the more complex the supply chain, the greater the impact.

DP: Thanks, John. I know you’ll be speaking to Rebecca Harding at Coriolis Technologies, who we spoke to last week, on some of these complex supply chains and how you can look to costing out the price of importing and exporting and actually optimise the supply chain and increase the flow at a more profitable level. This week, TFG launched its white paper on the global state of Supply Chain Finance. We looked at the SCF market, focusing on UK-China corridors. Clearly, there is a potential opportunity here in light of the UK exiting the EU, and in light of US-China tensions. However, in both markets, CFO’s consistently report challenges around accessing finance, releasing liquidity and working capital from their supply chains, and the need to explore other forms of trade and SCF, such as off-balance sheet finance and securitisation.

Coupled with the current outlook is the regulatory treatment of trade finance, namely basel III where bank intermediated trade faces challenges. John, how has the financing of trade changed as the global financial crisis?

JB: One of the dubious benefits of having been around a while is that you see patterns emerge, which you’ve seen before. And trade finance has always been a cyclical business. Going back to my earliest days, trade finance was exciting. Everyone wanted to do it, the banks all invested in it and had huge correspondent networks, a global presence, and it was the thing to do. It became less fashionable as derivatives, capital markets, equities, and corporate finance became the place where you made big money. And films like Wall Street – greed is good – trade finance was distinctly unfashionable at that point. In fact, transaction banking generally was regarded as an operations business. This is not something you brag about, if you’re good at trade, you’ll go to invoice finance, and this is something you just did and try to keep it under the radar.

Before the financial crisis, all the banks were really committed to investment banking, because that’s how you make lots of money. Sadly, it turns out that is also how you can lose lots of money extremely quickly. And transaction banking, once again became popular, it became stable, and it became the opposite of so-called ‘casino banking’. So transaction banking is driven by customers. It’s not driven by placing a bet on a future movement of a price – every trade finance transaction relates to an underlying movement of goods or delivery services. So it’s entirely customer driven. And in that sense, it is the ultimate honourable business that any bank or non-bank finance provider can be in, in my view.

About the time of the crash, the banks were quite keen to say, actually, we’re really good at transaction banking, because look how we support industry – we make payments, we lend money to finance, international trade and this is a good thing. So we’re actually really good guys. The immediate aftermath was a promotion of trade. Unfortunately, it coincided with a collapse in trade, because of the financial crisis. So it became quite difficult for banks to invest in a business which was shrinking, the way trade finance was provided. And I’m not talking about the big-ticket structured trade deals here, I’m talking about the mass market supply chain type deals – it became difficult to make a lot of money doing that business, because the volume of business available went down in the immediate aftermath of the crisis.

So banks reacted by trying to create transaction banking businesses as self-contained businesses, if you bolt enough of these businesses together, it creates a balance sheet and a profit and loss account which looks reasonable. They didn’t really compensate for the fact that the global markets for international trade had declined and have only really relatively recently started to pick up in any serious way.

So banks reacted by trying to create transaction banking businesses as self-contained businesses, if you bolt enough of these businesses together, it creates a balance sheet and a profit and loss account which looks reasonable.

John Bugeja – Trade Advisory Network

So that’s a positive step after the financial crisis. Unfortunately, the negative was the imposition of compliance regulations at a much tougher level, it’s not that they’re not needed, it’s just that they impacted trade perhaps disproportionately, relative to its real risk. So doing trade finance business became more difficult from a capital adequacy perspective, and also from a KYC, anti-money laundering and sanctions compliance perspective. So the cost of doing this business just got higher, and I think the consequences of that, or those changes, has been in the global corporate space, the major investment grade client segments, the banks can still deliver those services, but it’s quite difficult to make an acceptable return because of the capital treatments. So they tended to move towards originating and then selling, not keeping so many assets on their balance sheet. All the banks could have single name concentration limits or Prudential limits and then, because they’re more heavily regulated than they used to be, these are biting more aggressively than they used to. So that puts a constraint on how much business the banks can do even with the large corporates for whom they have a lot of credit appetite. So they’re constrained there. As you move into the

DP: Thanks, John. I know we’ve published quite a lot about the Trade Finance Distribution – Originate to Distribute initiative. Lionel, non-bank financing offerings are increasingly coming to the scene, as many institutional funds, technology providers and other new players consider the potential for the trade finance market. But there’s still a long way to go. And you mentioned the $1.5 trillion trade finance gap earlier – why isn’t there much institutional money and non-bank finance facilitating trade right now?

LT: We speak to many funds and institutions that have pockets of liquidity looking for yield. To be honest, they’re more attracted to the banks; whether they’re buying the assets off the bank’s balance sheet because it’s a bigger volume. So naturally, they’re drawn to support the banks. That’s certainly what we’ve noticed. The challenge, of course, with that type of distribution is if I’m buying directly from a bank, at least I know what I’m getting. If that parcel of asset is being sold by a bank to one party who sells it on to another party, etc. I personally have fears as to what that might lead to, and let’s think about the financial crash that happened, in the subprime market – are we going down the same route, depending on how far removed you are from actually the principal who was originating the asset, and that, if I’m honest, does worry me.

But in terms of the non-banks, they generally entered the market initially after the crash by slating the banks, and a lot of players came in with a promise: you use us when you need us, and we’re nicer, we’re friendlier, we’re now having technology to make it easy to onboard, you know, it’s automated credit, etc. So there were a lot of promises made, but it’s very hard to scale those businesses, because at the end of the day, most companies, no matter how much they would select, the banks rely on the banks. The banks already have all the assets of security, so they have a charge or pledge over every asset. So it’s a lot harder for the non-bank to carve out their bit. The other challenge that’s happened is that a lot of the non-banks were initially funded by some of these institutions. And they were promised the high yields. But the volumes are so small, that in the whole scheme of things, a lot of these funds are saying actually, is it worth it?

So there is a challenge for these non-banks, in terms of scalability, in terms of how they scale. We’re seeing a lot of the new technology coming in, to try and partner with the existing banks, because it’s the banks that have the client base. And there’s some initiatives in some countries, and we know in the UK, the initiative, that if the bank can’t provide the funding, then it should be passing the deal along to an approved non-bank. And there’s varying stories as to how successful or not that is. And actually, you speak to some of the non-banks, and they say it’s all marketing. And at the end of the day, they have a bank track to pass on all the problem clients to the non-bank.

So, it’s a bit of a mixed bag, currently. I mean, the truth is, for the markets to support that $1.5 trillion gap, you need the banks to play. When it comes down to it, there can be a lot of initiatives, and the banks are supporting some of those initiatives. But it’s the banks invariably that move the market. So the challenge in the developed markets is, as John mentioned, the retention of capital, the focus on the best return for the least effort and cost, a lot of the consortiums we’re seeing in trade are promising wonderful things. But it’s really starting with an efficiency play for the banks to make what they’re doing today more efficient, which doesn’t necessarily increase the level of funding to the customers.

No one is actually saying at the moment ‘we have more data available to us so therefore, we will now extend our funding earlier into the supply chain’, I think it will come but it’s not happening on a big scale today. When you move out of the developed world into the developing world, then you have a challenge of a skill base. So a lot of the banks in Southeast Asia can provide funding alone, they’re happy providing a loan against an asset, a lack of property. But they’re still not equipped and skilled enough as yet to provide finance, for working capital against what we will call a moveable asset, which is normally a receivable.

And there’s a lot of effort; we’ve got the ICC Academy, London Institute of Banking and Finance, a lot of sort of pushing of skills and training to help equip these banks to start providing those type of facilities to smaller companies. But of course, you need to change the regulation, it’s no good having a technology without the training. It’s no good having technology training, if you haven’t got legal regulations in place in the country that support the financing of receivables so that someone can actually say: I’m financing that receivable it’s registered. I don’t honestly believe it’s the non-banks that move the market. But it’s the non-banks that sort of throw the darts into the dartboard that start to provoke some discussion and some movement.

DP: I guess the idea that the non-banks and maybe even technology providers can almost catalyse that. But ultimately it will be banks that will be deploying that capital in the end. That’s very interesting, the idea of thinking of banks as partners, as opposed to competitors in our world. And finally, we talked about it quite a lot, the trade finance education gap, but it’s a big issue, particularly in developing markets, but even in well established markets.

LT: I was going to say, we talk about Ali Baba and Amazon – some of these big data capturers who are turning their hand towards providing finance. And there’s no doubt they will have an effect because they will often cover the tail of suppliers in the supply chain that are not being reached by major programs.

The interesting question is what happens when there’s a real downturn? Because so often we’ve seen in the past, non-banks, and often it was the logistics companies in the past, came into a market, which started to provide finance, which wasn’t really core to their main activities. And as soon as the market conditions have changed, they pulled away and who was left, it was the banks. So I know there’s a lot of talk at the moment about a lot of these non-banks getting involved. But there is a question, in an economic downturn, will they still be willing to play? Or will it again be the banks that are left?

DP: Very interesting and thought-provoking. To conclude today’s podcast, I’m going to ask both of you the same question. What is your short-to-medium-term outlook on trade and trade tensions, and where do these trade tensions leave the international trade finance market?

LT: Trade is not going to stop. We’ve already mentioned that as China and the US have that situation at the moment, some of those exporters and manufacturers move their production to other countries. And that doesn’t happen overnight. So one might say that Vietnam and other countries in Southeast Asia are benefiting from the trade war between China and the US. And I guess if you move operations into another country, you’re not going to pull them out very quickly. Trade finds a way around all these obstacles. And I think that’s what will happen. I think we see things with a very short-term effect, but I think in the longer term, trade will continue, although there’ll be bumps in the road. But I still believe that the opportunity, in terms of supporting and financing trade will still exist, they’ll still be demanded, and there will still be some good returns. If anything, the technology that’s coming along is going to aid those developments. not hinder. I see a very good picture for the future.

I still believe that the opportunity, in terms of supporting and financing trade will still exist, they’ll still be demanded, and there will still be some good returns. If anything, the technology that’s coming along is going to aid those developments. not hinder. I see a very good picture for the future.

Lionel Taylor – Trade Advisory Network

JB: Okay, let’s just focus on Brexit and the European Union for a second, just illustratively. A lot of scaremongering is centred on how if we don’t have a trade deal, trade is going to stop. We know that’s not true. Lots of trade happens without a trade deal. So, as Lionel said, trade has a habit of working itself out. So the trading companies, not the politicians, decide where they’re going to buy and where they’re going to sell. And if conditions become a little bit more difficult they’ll find a way around it over a longer period. It might be disruptive in the short term but not over the long haul. It’s not all about the politicians putting trade deals in place. What does impact trade is the uncertainty. Because it’s difficult to plan and change your sourcing and your selling model, if you don’t know what the scenario looks like, you don’t know what the circumstances are going to be. It’s the uncertainty that causes more trouble for trading companies than the actual imposition of tariffs, once the tariffs are there, they can make decisions. I mean, they may be damaging, everyone might get a little bit poorer as a result of the trade war, if the trade war becomes the new global model. But over time, things happen in cycles, there will be some protectionism, perhaps it will be a cure, perhaps we will get a little poorer. And then there’ll be a realisation that a more open approach to trading globally does help everyone, and hopefully, these barriers will reduce. It’s the uncertainty that causes a problem. So I’m not that worried in the sense that once the decision is made to impose tariffs, or agree free trade agreement, or leave the EU, people will get on with making it work.

The bigger challenge is education, which is needed irrespective of whether there are free trade agreements in place, or whether there are trade tariffs. There is a lack of education and education leads to policy within the lending institutions. And the policy change, coupled with education, leads to increased appetite to support companies to trade internationally. So it’s not technology –

There’s two old sayings: ‘you lend cash then you want cash back’, fairly self-evident. And the other associated saying is ‘tangible security on property does not make a good source of repayment for a trade transaction’. So why is it that even in the developed economies, most lending to SMEs is underpinned by guess what? Fixed asset security – tangible security over property! It doesn’t make sense. It doesn’t allow businesses to grow, that’s even more the case in emerging markets. So we need some education about understanding the trade cycle and how you can track and control exposure. One of the applications of technology which has been underplayed I think, is how can you use technology to track and control your exposure, to track the goods, to maintain security and the goods in order to ensure that you do get paid and you do get your cash back. Those are all applications technology, which have not yet fully developed. The technology exists, so it needs to be accompanied by education and policy in order to work and that’s a bigger risk or opportunity from debates about protectionism.

DP: Great. Well, thank you very much, John and Lionel. Now, I’m really looking forward to hearing from you here at the ICC Banking Commission Annual Meeting!

JB: Thank you.

LT: Thank you.