Listen to this podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Podbean, Podtail, ListenNotes, TuneIn, PodChaser

Season 1, Episode 33

Host: Deepesh Patel, Editor, Trade Finance Global

Featuring: Sukand Ramachandran, Managing Director & Senior Partner, BCG

Trade underpins the evolution of mankind, and with trade comes trust, and with trust comes third parties. Moving forward from IOUs and promises written on clay tablets thousands of years ago, to today’s interconnected world of trade, I want to question how far the industry has really gotten to, in terms of innovation and true digitalisation. Buzz words aside, TFG was joined by a world-renowned expert in trade and trade finance; BCG’s Sukand Ramachandran. Sukand is a leading expert in technological trends, as well as the complexities and nuances of cross border trade, trade finance and payments.

DP: I’m Deepesh Patel, editor at Trade Finance Global. Now trade finance is one of the oldest forms of finance in history and trade really underpins the evolution of mankind. With trade comes trust, and with trust comes third parties. Moving forward from IOUs and promises written on clay tablets thousands of years ago to today’s interconnected world of trade; I want to question how far the industry has really gotten to in terms of innovation, and true digitalization. So buzzwords aside, I’m joined by a world-renowned expert in trade and trade finance, BCG’s Sukand Ramachandran. Sukand is a leading expert in technological trends, as well as the complexities and nuances of cross border trade, trade finance and also payments. Sukand, thank you very much for joining us on Trade Finance Talks. So quickfire elevator pitch, who are you? Where are you from? What do you do?

SR: I’m Sukand. I am originally from India, senior partner in the London office of the Boston Consulting Group. And I do a lot of stuff as you said around trade.

Full end-to-end Automation and Digitalization in Trade: A Myth or Reality

DP: So I’m going to start with a challenging statement. According to research trade finance originates from Babylonian clay tablets dated around 3000 BC. These were the first examples of promissory notes and letters of credit. Since then we’ve moved over to paper document possibly to Excel documents. But we haven’t seen any real examples of full end-to-end automation and digitalization, I don’t think we’ve progressed much in trade finance since clay tablets. Do you agree?

SR: I will agree and disagree. In the same sentence, I would say. I think there are enough examples of transactions on a global end-to-end basis which are on newer technology. Even if you look at the FT headlines, there are many banks which have quoted that they’ve done blockchain transaction. So, there are a handful of transactions on the blockchain. Now, is that fully digital? Debatable, because basically, the internal processing systems are not fully plugged into this blockchain ecosystem. So, I’m sure there are a lot of people who would do post-trade activities manually. On the other side, I agree that trade finance, it is still a very face-to-face activity. It’s still manual. It’s still very judgmental based on humans. As you said, right at the beginning the genesis of trade was very much around trust and face-to-face interactions between merchants and money lenders to an extent. I think some of that still exists today. Globalization’s ensured, the face-to-face doesn’t necessarily need to be proximate, could be on trust-based networks, and using videos and other digital communication forms. But the level of trust is dependent on levels of interaction. So that hasn’t changed.

The Future of Paperless Trade

DP: According to the recent article on the Economist, trade credit requires the exchange of some 36 original documents, and 240 copies on average per transaction and each of the 27 parties approximately involved spent hours, if not days fact-finding and form-filling. How come is this possible?

SR: I think it’s partly a function of globalisation. I guess if you go back to the Babylonian mall, it was all about being on the Silk Road or part of whatever trade networks. Now, if you think about the fact that we have 200 different countries, legal jurisdictions, each with different levels of exports and imports, and a lot of it happening also domestically in large geographies, where there is no trust between the buyer and seller.

What I mean by that is, I believe that I can give you the money or give you an order and you will deliver what you promised at some point time in the future to the right quality to the right quantity, that level of trust where there is no risk involved, there’s a role in some form or shape of trade finance providers being in the middle. The more global it is the more participants are there- they might be common customs regulators, they might be insurance companies, they might be shippers, they might be multiple shippers for freight forwarders. So globalisation meant that the number of parties has exponentially expanded. That’s why you see the complexity. It’s a simple domestic transaction between Lamont and some of the part of Southern Nile, which may have been where the original collections happened, that may not have involved that many parties; there must be a merchant who transports goods. There’s somebody who buys, somebody who sells now it can go from a Chilean background to deep interior China and it passes through three or four middlemen to make sure the trust equation works and then you have different parties who are playing the trust conditions between the buyer and the seller.

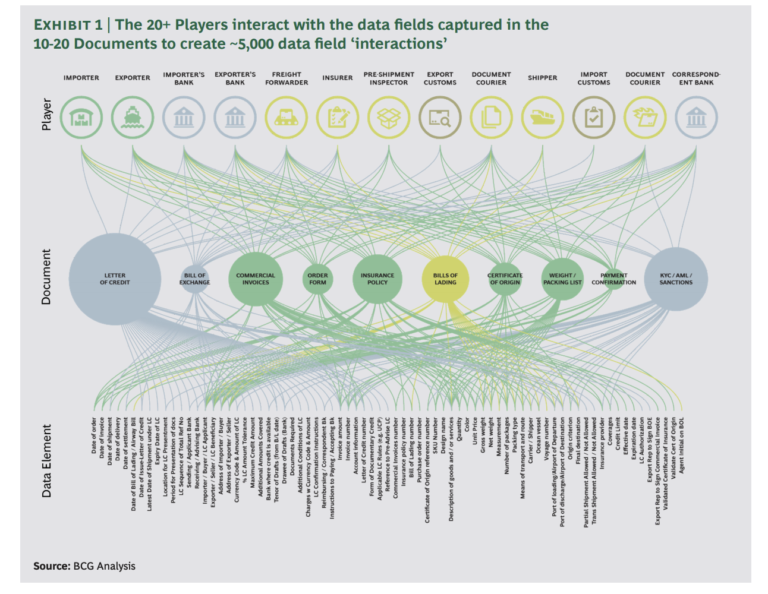

DP: So guess a mixture of both trust and the nature of the complexity of global supply chains today, and I was at the WTO Public Forum in Geneva a couple of months ago and our UK delegation, presented one of your diagrams and showed the complex web of different documents, silos and products involved with trading a product or service from one place to another. So there’s two questions here. How does our industry untangle this mess? And also how individuals incentivize digitalized trade finance, as an industry to make it simpler?

SR: Well, I’m glad at least they used that graph because when we did that a year or two ago, it was really about step one of what you’re asking for; how do you untangle this is to first acknowledge the complexity that we live in? I think we did that exercise working with SWIFT and some of our clients to make sure that there is something like a common currency of understanding of the levels of complexity in a way that is unbiased. It’s just saying these are the facts on the table. Step one of untangling anything is just awareness. Step two of that is to say then who are the parties that contribute to the complexity? And then how can they reduce the complexity? And how do they make the interactions easier? Now, part of that is making sure that we have better standards, a better understanding of the key critical data elements required to engender trust. And then how do we make sure that the parties who need the relevant data elements get that and not the unnecessary extra, which will always happen?

A lot of that superflow stats exists because there are physical documents in totality flowing through the system. Each party needs only a small subset of the whole information in those documents, but they copy it just in case somebody refers to it again. So that’s why you get the cascading effect of lots of information flowing through, of which only a very small proportion is relevant and useful. And so first is an acknowledgement of the problem. The second is to make sure that everybody knows which party needs which critical pieces of information, and then find a mechanism by which you can actually access that simply. In that paper, we refer to the fact that it wouldn’t it be nice to have an information fabric where all the data elements are available on subscription for anybody who’s interested and on a permission basis, who owns the data makes it available. And if you think about a feature like that, where the data is accessible on a controlled basis for anybody who needs it, and they add any additional data elements onto the information fabric, you flip the problem from data moving in big chunks of paper, electronic fine or not through the system to data stays in one place. But ways do it to you it might be having some central parties which provide the data standard. And I’m glad to see that the ICC is starting to move on that basis, especially from their intention coming out of Singapore next year, defining the data centres. And once you have the latest handles, I’m sure there will be multiple providers willing to provide the information fabric.

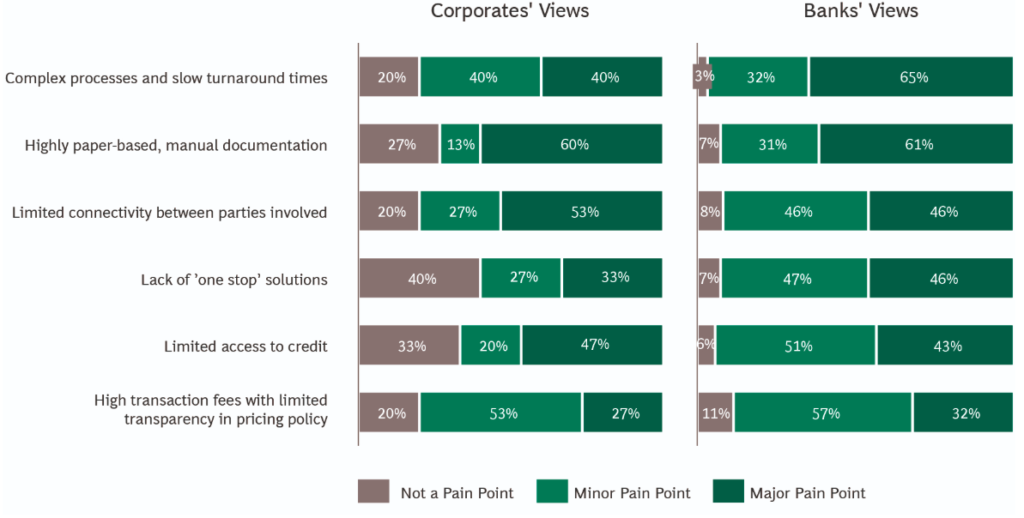

What are the biggest ‘pain points’ for corporates and bank?

DP: And potentially the ICC DSI projects could provide that Data Fabric layer, which could be very interesting. What are the biggest breakthroughs from both a bank and a corporate perspective, in terms of removing some of those barriers and pain points for trade finance?

SR: The simplest thing is again, if you go back to what we know and what exists, right, the SWIFT network is a good one to think about. The SWIFT network made it easy for banks to interact with each other on a trusted basis and send messages to each other which people could act on with absolute faith and trust and add mechanisms for reparations or reconciliations if required if something breaks in the process. I think what banks and corporations are moving towards is finding mechanisms for cooperation through other means. Whether that’s blockchain or not. That’s just like a specific technology, the technology of today might be blocked in the technology of tomorrow might be something else. For me, the critical thing is making sure that large institutions which are critical nodes in the global trade ecosystem are very clear about how they want to exchange data, make their data standards and capabilities available on an open basis. The more open the standards are, the more cooperative the sector is, hence there is less friction for everybody involved. The counterforce here, interestingly, is if you are the largest player and you make the environment open, there’s a fear that you will suddenly become disintermediated. I think that’s the trade-off that everyone is going through. Do I want disintermediation, where smaller bank operating in very small geography can interact directly with another small bank or another corporate at another end of the world without the need for some of these large players to be the intermediaries? My view on that one is you will still be relevant as long as you’re adding value.

DP: It’s interesting you talk about that disintermediation from the small place. I was at the World Trade Symposium, a couple of weeks goes out in New York and I guess, that big piece around the two big global powerhouses US and China and now potentially in talks about splitting up the internet and actually controlling a larger proportion of their own data. So yes, I question that sharing model, what about whether it be the biggest banks in the world or the biggest countries in the world, not wanting to share that data, which is ultimately that power to control perhaps over the trade flows, etc.

SR: By the way, it’s not just China and the US, right. So data protection has been there. And data localization laws have been there in many countries for a long period of time. It reduces one element of friction. But digitalization of data changes the dynamic that little bit right all that happens is now I’ll have two electronic copies of the same data one in China, one in the US, one in Indonesia, one in India, one in somewhere else, right. If you are part two, you will just keep a local copy of it and then transfer a copy of that, which may be stored locally somewhere else as well. So you may need to refine the idea on common singular information fabric into an alternative model which says there’s no Permission fabric which may have localised copies of local information but connected through same common standards on to some global network. It’s just ways to make it work.

What is the digital island effect?

DP: Actually, what I would say this is happening right now. And I think you refer to it in your papers, the digital island effect. So what is the digital island effect? And what’s happening within this industry right now?

SR: I think, well, there was no standard definition of in digital island effect. But in the winter, it’s a metaphor in a way to think about everybody doing elements of digitization, but doing it to their own standards and capabilities. And therefore you basically create electronic repositories of information which often look different depending on who’s doing it and when it’s been done. If you’ve done contrast that to that futuristic vision, we hand off an information fabric where it is one common data standard, one data repository, control lacks, because trust matters, the digital islands are a different model in a way and we need to find how do you get from those digital islands to a more interconnected set of their foundations? My sense is there are two different views of the world. Different people will subscribe to different solutions.

2020 Predictions for the Trade Sector

DP: Very interested in 14 minutes we’ve gone from the history of trade finance from the IOUs on the clay tablets to the digital islands and potentially this futuristic view of that digital fabric that layer. So we’re coming to the end of 2019. And what a year it’s been. I’d like to ask for your crystal ball now. And as take 2020 starts off with and you’re not allowed to use the B-word Brexit, blockchain or trade was to make this a little bit more exciting. What are your predictions for trade and trade finance in 2020?

SR: It’s a difficult one I guess. I wish I had the crystal ball but I would say we will see more positive momentum. I’m cautiously optimistic about some of the ICC initiatives and some of the work that the SWIFT is doing in terms of driving commonality and standards across the participants in the trading network. I would expect some of the work being done by the ADB towards making trade-related financing accessible to SMEs starting to bear fruit in multiple geographies that’ll help. Africa will get on the map even more. I think there is a lot more activity happening in Africa. If you think about global trade, with the exception of a handful of players, Africa is the sort of forgotten continent. I think it’s becoming more and more mainstream. So notwithstanding the words, I’m not allowed to speak it that I think there is more globalisation, more interconnectedness and yes, we will have to work our way through the frictions.

DP: And do you think we’ll see any either consolidation or failures within some of the technologies initiatives that are going on right now.

SR: There are quite a lot of initiatives going on and everybody doing their own thing. So yes, there is the natural state of evolution of digital activities, right that some of them will not succeed. Some standards will become the de facto standard for the whole industry. That’s the natural state of evolution of anything digital. Yes, there will be consolidations. Yes, they will be successes, yes, there will be some which will die.

DP: Sukand it has been a pleasure having you today on Trade Finance Talks, and thank you very much for sharing your views on that digitalization aspect in the digital fabric and also for your predictions to 2020 Thank you for coming.

SR: Thanks, Deepesh.