Listen to this podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Podbean, Podtail, ListenNotes, TuneIn, PodChaser

Season 1, Episode 13

Host: Deepesh Patel, Editor, Trade Finance Global

Featuring: Michael Vatikiotis, Author, Journalist and Conflict Moderator

Easternisation: Blood and Silk, Power and Conflict: The Role of Modern Southeast Asia in the Global Economy

Deepesh Patel: I’m Deepesh Patel, Editor at Trade Finance Global.

Now we’re here live today, in Ho Chi Minh City, formerly Saigon, Vietnam’s financial center, here at FCIs 51st Annual Meeting. FCI is the world’s largest open account receivables finance network, dedicated to the growth of cross-border trade, and here at Trade Finance Global we are delighted to partner with FCI at this wonderful event!

Modern Southeast Asia is one of the fastest growing regions in the world, and is one of the most diverse. We have deepening divisions in religion across Indonesia and Malaysia, we have violent insurgencies still in Thailand, Myanmar and the Philippines, and the continued influence of China affects the region.

I’m delighted to be joined by Michael Vatikiotis, who was the keynote speaker earlier today in the conference, an experienced author, journalist and conflict moderator specialising in Southeast Asia.

Deepesh Patel: So tell us a bit about yourself, your story, and experience in Southeast Asia, perhaps starting from when you first moved to Thailand as a student?

Michael Vatikiotis: Thank you. I arrived in Thailand actually, having already learned the Thai language, as a student in London, which is a strange experience, learning about a language and culture so distant from where I was, in the United Kingdom, and never having been there. When I got to Thailand in the late 1970s, it was 5 years after the Vietnam war, there was still very much the evidence of the Cold War in Asia; a virulent fear of communism, the beginnings of an economic boom and the first signs of the explosion of growth and development that characterised the next 30 years. I went back to London and became a journalist at the BBC, who eventually sent me back to Indonesia, where I was a correspondent, before I joined a magazine based in Hong Kong, called the Forest and Economic Review, as its Jakarta correspondent. Then I moved to Malaysia, Thailand and eventually to Hong Kong as an editor.

ASEAN as a strategic highway connecting East and West

DP: Thank you, Southeast Asia is a strategic highway connecting east and west, which has some two million square miles of land and 613 million people. Can you give us a backdrop on the region having worked in for Southeast Asia as major cities crossing all 10 countries in ASEAN?

MV: The most popular narrative for the story of Southeast Asia is its remarkable growth and development since the mid-1970s. There is simply no way you can exaggerate the impact and extent of high levels of economic growth, averaging in some cases, 8% to 10%, for a year, over a decade, such as we’ve seen here in Vietnam. Then there is the role of private and foreign investment, and the amazing capacity by both governments and the private sector to look after the capital and banking regulations with remarkable efficiency, very little profligacy and low levels of debt. These have been remarkable conditions by any standard for a region to grow and prosper.

Of course, the dark side or underside, is very high levels of inequality. Also, I think, very patchy governance, especially when it comes to effective governance for issues like corruption and pollution of the environment. With the decentralisation of government, there is a patchy record across Southeast Asia. I think it’s very important to point out that one of the key aspects of growth and development in Southeast Asia has been the role of the Overseas Chinese community, which forms the core of the business community in most countries, and is very cautious, very careful, but at the same time, highly entrepreneurial, and very successful.

Easternisation

DP: Thanks, Michael. Eastern centralisation is a common theme, which has been discussed regularly. Asia is the world’s economic trading hub, containing 60% of the world’s population and almost half of global gross domestic product. Asia has proven resilient to boom and bust cycles and continued growth. So, what are the opportunities here?

MV: I think that given the growing sensuality of Asia, in global trade and finance and commerce, one of the main opportunities is basically to now reconfigure some of the institutions that govern trade and banking, and start to encourage not just the larger countries, but the smaller and medium sized countries as well, to play a bigger role in the retooling and reshaping of the financial commercial landscape. This is not easy, because we’re looking at a decline in the role and importance of the countries and the institutions that shape the post-war global order, mainly in Europe and North America. And there is a reluctance to allow this transition to happen, because it means for many Europeans and North Americans a loss of centrality. I think if everything is now going to be more or less centred on Asia, it’s important for Asians to play a bigger role in not just exploiting the opportunities, but in shaping the standards of governance and institutional development.

The Return of Geopolitics

DP: Over the next few decades, Asia faces a big challenge of wearing the mantle of economic growth and sensuality. What are the biggest challenges here?

MV: I think there are two main challenges that affect stability, which is the key to enduring economic growth and prosperity. I think the first main challenge is that Southeast Asia and Asia in general is an extremely diverse part of the world, full of ethnic groups with different religions, all living side by side, managing to live peacefully together. But this has started to change with a greater move towards communal, ethnic and religious tensions, not just in Asia, but also in the world. In Southeast Asia this is particularly sensitive and difficult, because there is just so much diversity, and it’s absolutely vital that all the communities are able to live together peacefully. When that sort of pluralism is disrupted, it actually leads to a loss of confidence which can then lead to violence and instability. I think it’s very important that the challenge of managing diversity is met, not just by governments, but by other societies as well.

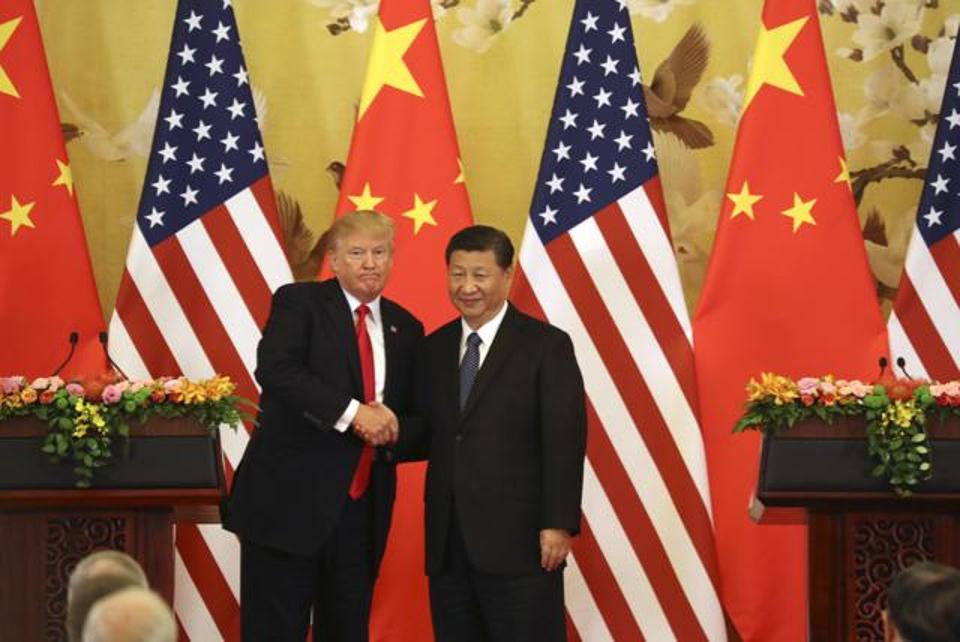

The second major challenge, which is less controllable in the region, is the return of geopolitics. China’s rise over the last 40 years has, of course, affected Southeast Asia. There have been growing levels of Chinese investment, and China’s strategic aims have been expressed in the region through the Belt and Road initiative. The worry is that if there is opposition to China’s interests, then she may exert herself more firmly in the region. In recent times, the United States has woken up to the fact that China’s rise is significant and it may begin to affect US interests. This has introduced a polarity into the geopolitics of the region, which is forcing countries in Southeast Asia to choose between support for the United States or for China, which none of the countries in the region want to do. There’s traditionally an equilibrium, a balance between the big powers, in this very fluid part of the world, which has always had close connections, east and west. So I think those are the two main challenges.

Overcoming the diversity issue is really down to good governance, effective law enforcement, and a balance between popular sovereignty and effective leadership. On the geopolitical front, I think it’s very important that the small and medium sized countries in this region really come together and play a bigger role in cooperating to sort of push back on these geopolitical pressures.

Blood and Silk: Power and Conflict in Modern Southeast Asia

DP: Thanks, Michael. I wanted to go into a little bit more detail on your first point. In your book, Blood and Silk: Power and Conflict in Modern Southeast Asia, you talk about some of the huge challenges in terms of religious conflict, such as secularism in India, Muslim and non-Muslim conflicts in Indonesia, and generally religious orthodoxy in many south-eastern countries. What’s the impact of these rising tensions on geopolitics and into regional trade?

MV: Well, in terms of the fractal pluralism, I think the biggest impact is on investor confidence. And the fears that one stable unit, with relatively unified populations and societies, will start to fly apart. I think the biggest fear has been in Indonesia, which is the largest country in Southeast Asia, with almost 270 million people, more than almost 90% of whom are Muslim, Sunni Muslims. Therefore, you know, the increasing trajectory towards orthodoxy, not just among Muslims, but around Christians as well, has actually created tensions in society. I think that it’s sometimes difficult for this risk to be highlighted because it’s a very sensitive issue in many of these countries. But what I see is that the success of democratic transition in some of these countries, like Myanmar, Indonesia and Malaysia, has exacerbated the divisions between the societies; as politicians seek votes, identity politics has come to the fore. And this has increased tensions which often leads to violence. I think that this is one of the biggest threats to stability, which therefore is a factor in terms of economic and commercial confidence.

Divergence of Technological Spheres – US and China

DP: Yes, and geopolitics is back – we’re seeing the divergence of two technological spheres, the east and the west. With the US recently banning Chinese technology and convincing friends and allies to steer clear of Huawei, as well as stories of China building a new operating system for new technologies, really ruffling the feathers on the other side of the world. What does this mean for the global interconnected economy and, in particular, for American values?

MV: Yes, this is a major problem for all of us. What if the United States becomes intent on reasserting itself commercially, technologically, in military terms, and geopolitically? What if they take it to extreme lengths and start to create a new sphere of influence that excludes Chinese capital, Chinese technology and Chinese influence? This puts all of us in a very awkward position because none of us really want to choose; we’ve grown used to the narrative of globalisation and of shared responsibility. Both the United States and China are big powers intent on pursuing their interests and they want their interests to prevail. But they haven’t yet been able to come up with a way of sharing the space and engaging in the concept of shared responsibility. I think the tech industry is quite concerned, because it will be a huge waste of money and opportunity if, say, Google is then cut off from half the world’s consumers. And don’t forget, it’s not just the Chinese market, but also maybe the Russian market and parts of Asia, that are not going to want to choose between the US and Chinese operating system. So I think these are real concerns. I don’t yet see a willingness on the part of the United States to back down and look at ways of creating a shared platform or shared responsibility in China. On the other hand, I think there’s a feeling that ‘well, we want to be part of the global rules-based order, and we want to start making the rules’. But there are fears in the West that if China starts to make rules, for instance, in artificial intelligence, they’re so far ahead in technological terms, they may start limiting access to technology from the west. So it’s a real geopolitical tussle that, unlike the Cold War of the 20th century, is starting to affect our lives. Because it affects access to technology and affects issues such as standards and governance. And this is a very serious polarisation, that we haven’t yet come up with a recipe for dealing with.

Deepesh Patel spoke at FCI’s 51st Annual Meeting in Ho Chi Minh City this week, discussing the Technological Makeover the Factoring Ecosystem is undergoing in South and Southeast Asia. Read more here.

Southeast Asia’s role in the Global System

DP: Thank you, Michael. Very interesting. Moving back to Southeast Asia and its interconnectedness with China and the rest of the world, what does the future look like for Southeast Asia? What’s its future role within the global system?

MV: I think the answer to that question is also that it depends on which country we’re talking about. The larger countries like Indonesia, clearly has had a thriving multiparty democracy for the last 20 years, with a great sense of its own identity and role in the world. It can increasingly play a role with other medium sized countries, like Turkey, Mexico, and Korea. Indonesia can also potentially play a bigger role in the international system; it is, I believe, the only country in the world that has built into its constitution a resolution to do good in the world. That is primarily because Indonesia earned its independence with the help of the outside world. For those reasons, Indonesia can be set apart. Other mainland countries of Southeast Asia are increasingly going to be on the frontiers of a growing China space, and therefore are going to be countries through which people will interface with China – Thailand has traditionally been a country that manages very carefully and successfully to survive on the doorstep of China.

I think potentially for the future, this means that these countries will be seen as intermediaries with China. Vietnam is a remarkably successful country to emerge from the ashes of a very costly war in 1975, to now be a major economy in its own right. It is growing very, very fast, with tremendous potential in all areas of the modern economy. The same goes for the Philippines – a huge country with remarkable human resources. So, we’re going to see many of these Southeast Asian countries emerging from long periods of transition and difficulty and playing a bigger role in different ways in global commerce, trade and diplomacy. As we move forward, they will contribute to the whole idea of reshaping the global world order.

The Role of the Business Community & Multilateral Bodies

DP: Thank you. So, it is incredibly important for businesses to understand the geopolitical and historic context here, particularly when dealing with China, and perhaps when dealing with markets in Southeast Asia. What role can the business community play in speaking out keeping markets open and staving off market polarisation?

MV: It’s an excellent question. I think one that’s not really being asked enough. I think that, the shock of the US-China trade war has sent the business community into different corners which they haven’t yet come out from. There’s been a little bit of commentary on how this is not good for business but, by and large, the business communities have divided themselves along the geopolitical divide. This is a shame because I think it’s important for business to advocate pushing back on polarisation and advocate reshaping of global rules to better suit the modern world. It’s just that there aren’t really the forums to do this. I mean, no one really talks about APEC anymore – the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation body that was set up in the 80s. No one really has much faith in the World Trade Organization, with the bigger powers essentially making it less effective.

So I think the business communities, along with medium and smaller countries, can create and shape a new coalition in favour of a more objective reframing of the rules. It is hard for businesses to rely on a US or a Chinese market, but I think it’s eventually going to fall to the private sector to put pressure on their governments to make sure that the rules are adapted to this new global situation, wherein China and Asia plays a bigger role.

DP: Thank you very much, Michael. It’s great to have you here today. I think for any trading businesses, it’s so important to consider the role of geopolitics, the role of South Asia’s interconnectedness with the rest of the world, and also as a gateway into China. We all need to be mindful of the fact that businesses who operate in different regions around the world need to speak to each other, both within markets and across markets, as well as to their own government and regulators, to ensure that we continue to thrive in a world where global commerce is good, and it’s good for trade. Thank you very much for joining us on today’s podcast, Michael.

MV: Thank you very much for having me Deepesh.