Listen to this podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Podbean, Podtail, ListenNotes, TuneIn, PodChaser

Season 1, Episode 11

Host: Deepesh Patel, Editor, Trade Finance Global

Featuring: Dave Sutter, Chief Strategy Officer, TradeIX

What do we need to do to make blockchain in trade finance? Dave Sutter, Chief Strategy Officer, TradeIX

Deepesh Patel: I’m Deepesh Patel, Editor at Trade Finance Global.

Not everyone is yet convinced of the use of blockchain and DLT, and recent attempts to digitize trade and trade finance have been pretty unsuccessful.

Consortia and networks have become a common method for businesses to collaborate on the use of blockchain and DLT, but there are many challenges ahead.

Internal processes have become increasingly digital but transactions involving multiple parties are still costly, complex, and largely paper based. This lack of success to date has been mainly due to limitations of legacy technology systems, platforms, and networks that supported these digitization efforts.

Trade Finance Global and TradeIX today have published a whitepaper: the global state of the market for blockchain and DLT within trade finance and shipping. We’re hearing from Dave Sutter, Chief Strategy Officer at TradeIX.

Deepesh Patel: So without further ado, here’s Dave, joining us live from London. Hi Dave, thank you so much for joining us on today’s podcast.

Dave Sutter: Hi Deepesh. Dave Sutter here, Chief Strategy Officer of TradeIX. I’ve spent almost seven years at the intersection of distributed ledger technology, also known as blockchain, and global trade, transaction banking, supply chains and trade finance. I’m here to talk to you today about the evolution I’ve seen in the market, the technology that is underpinning those markets and the participants there.

DP: We see how even in 2019, trade is so paper based and reliant on such legacy software. Can global trade really become digital and connected?

Can global trade really become digital and connected?

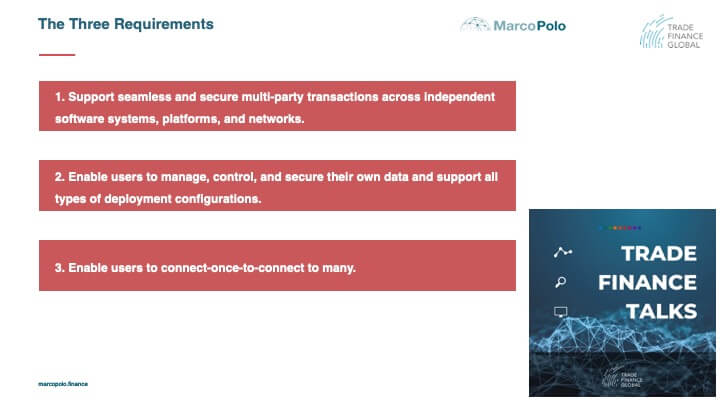

DS: This is the opening question of the article. The reason we ask it is because there have been decades and decades of effort, with significant time and money invested in making global trade a much more digital and connected activity. By any stretch of the imagination, we’ve been successful. So trade, finance, and global trade is one of the most important and socio economically and macro economically important sectors of financial services. However, despite that, we still have a very manual, inefficient, disconnected ecosystem that’s still dependent almost entirely on paper. So the question is, after so much time and effort, is it possible to make global trade connected and digital? The answer, fortunately, is yes. But as we’ll discuss over the remainder of this presentation, there are three key requirements for any technology platform or network that supports digitisation and connectivity.

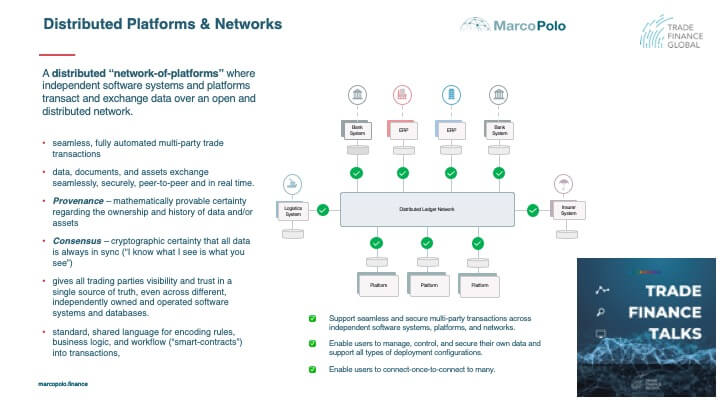

The first requirement is to support seamless and secure multi-party trade transactions across independent software systems, platforms and networks. So, allowing the seamless and peer to peer, as well as real-time exchange of trade data and assets between all the various systems that we depend on to facilitate the flow of goods flow, money flow, credit and supportive trade.

The second requirement is that we provide solutions that give users the right, but not the obligation, to manage control and secure their own data in any way they see fit. Moreover, to deploy these technology systems, under any configuration, so that they can satisfy a regulatory requirement and/or an organisational requirement.

The last key requirement for technology that can and will digitise and connect global trade is a technology that enables users to connect. A technology infrastructure should require only a single integration, a single interface that, once performed and connected, gives you seamless access to everyone else on the network. Something analogous to this would be email; once you have an email address, and a single email client, you can communicate with anyone else in the world that has an email domain name without requiring an integration.

We need to apply that same concept to global trading technology and trade networks. While legacy paradigms, which we’ll discuss here, have been able to meet one, maybe even two of these requirements, they’ve never been able to meet all three requirements simultaneously. So we’ll discuss how new technologies specifically distributed trade networks and platforms are able to meet all three requirements simultaneously. And as such, can actually digitise and connect with global trading ecosystem in a way that we’ve been working towards for several decades now.

Trade Finance Platforms, Consortia and Networks Explained

DP: What do you consider a trade platform and/or network?

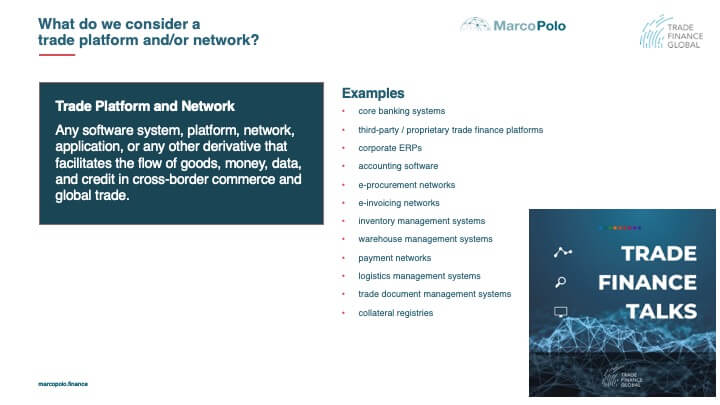

DS: Yeah, this is a really good question. The term ‘trade platform’, or ‘trade network’ is pretty generic. In this case, what we mean by trade platform or indoor network is any software system, platform, network, or application, or – really – any other derivative that uses software and technology to facilitate the flow of goods, money, data and credit in support of cross border commerce and global trade.

So some examples that we can think of that we consider for purposes of this discussion, as a trade platform or network, our core banking systems, third party trade finance platforms, corporate earpiece and accounting software, procurement and invoicing networks, inventory management and warehouse management systems, logistics management systems, and cloud registries. In short, any and all the digital systems that trading parties, banks, fire sellers, logistics companies, insurers, and others use to conduct global trade is what we would consider, for purposes of this discussion, the ‘trade platform’ or ‘trade network’.

The Definition of Truly Digital Trade or Connected Ecosystems

DP: What do you qualify as a truly digital trade or connected ecosystem?

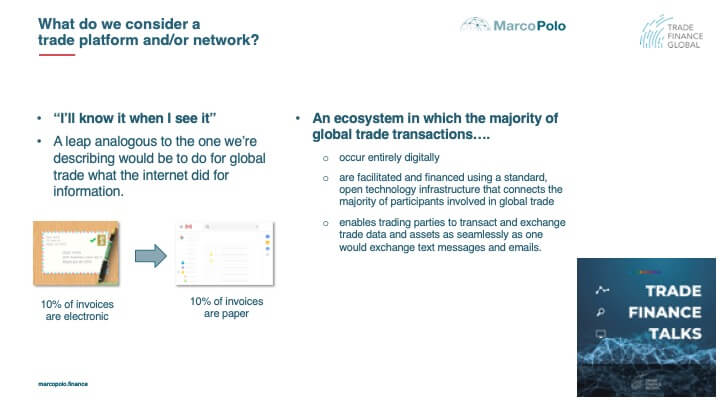

DS: So when we say, a truly digital and connected global trade ecosystem, this is really an ‘I’ll know it when I see it’ moment, which is that when global trade really is digital and connected, there won’t be a question whether or not it is digital or connected. It appears that we are still so far away from it, when it’s obvious that we’re not. But if we want to provide more specificity to this definition and then qualify it, it would be an ecosystem in which the majority of global trade transactions occur entirely digitally, and are facilitated and financed using a standard and open technology infrastructure that connects the majority of participants involved in the conduct and financing global trade.

So when we say, a truly digital and connected global trade ecosystem, this is really an I’ll know it when I see it moment

Finally, it is an ecosystem that enables all trading partners to transact an extra change trade data and exchange traded assets as seamlessly as they would exchange text messages or emails. What we want to achieve for global trade is similar to what the internet did for information.

Where before, a vast majority of male communication was entirely paper-based using the post office, the majority of business to business communication is by email now. We can look at the sort of examples where the dynamic would be the same in global trade where today, only 10% of invoices sent each year are electronic. So, of 170 billion invoices sent globally each year, only 10% are electronic. In a digital and connected trade ecosystem, we would see that number flip on its head, with only 10% of invoices paper-based. The other 90% would be sent electronically and by a standard infrastructure in the same way that paper mail is now sent electronically by a standard infrastructure that we call email or electronic mail. This is the type of leap that we’re looking for when we define a truly global and connected trade ecosystem.

Mass Adoption and Scale for Networks and Consortia

DP: Why is global scale and mass adoption such a hard requirement in the global ecosystem that we see in the world of trade?

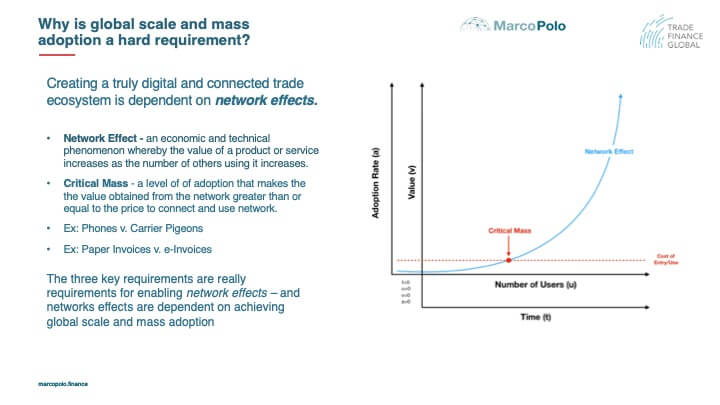

DS: Right. So when you read the article, you’ll see that all three requirements enable global scale and mass adoption. The failure to meet one, two, or all three requirements and meet them simultaneously, prevents global scale and mass adoption. Any technology solution that wants to become pervasive and must digitise and connect, depends on network effects.

For those of you who are unfamiliar with the concept of network effects, this describes an economic and technical phenomenon whereby the value of a product or service increases as the number of other users using it increases.

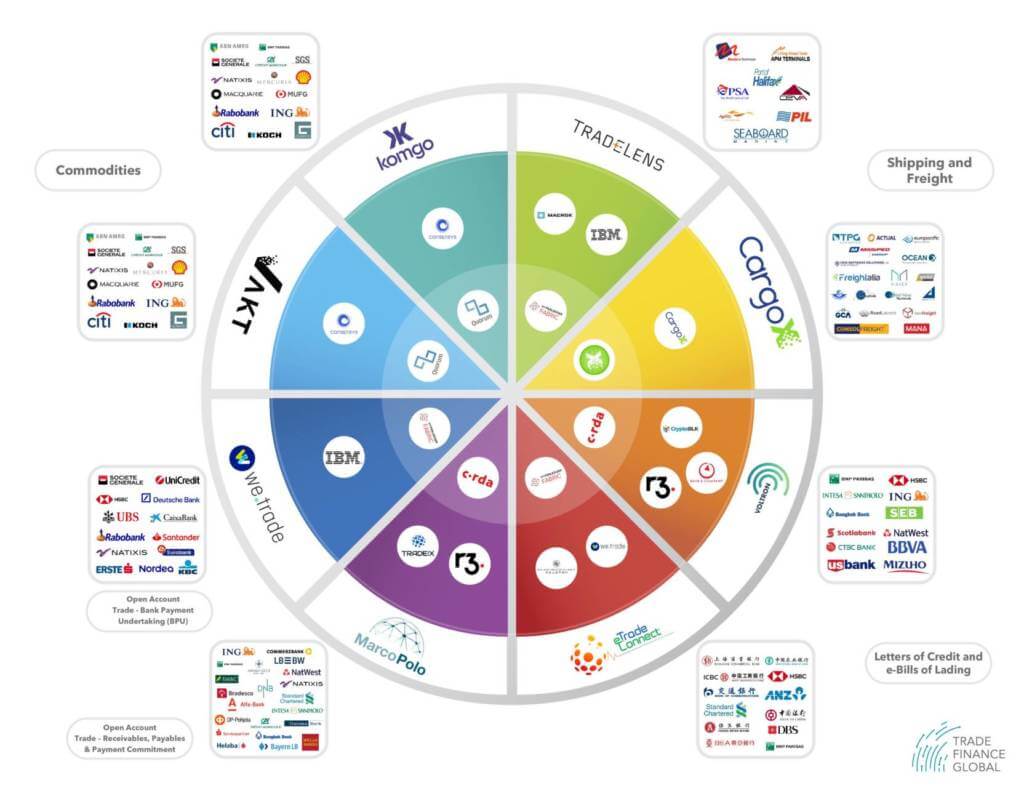

See our article: Map of the Networks and Consortia in 2019

The Network Effect

DS: A good example of this in action is the telephone. If I’m the only person in the world with a telephone, and everyone else is using carrier pigeons to communicate, even though my telephone is definitely going to be more secure, and more cost efficient, and much faster than carrier pigeons, my phone at that point is useless to me. Why? Because there’s no one else on the planet that has a telephone! But as more and more people start buying telephones, and more and more businesses start buying telephones, the value of my phone goes up, because I can actually now use it to communicate with a certain percentage of the people in businesses I need to communicate with when I do and I use the phone – it’s much more secure, more efficient, and much faster. At a certain point, what will happen is that the telephone network will reach a critical mass, which is a certain percentage or level of adoption, which makes the value obtained from that network greater than or equal to the price of connecting and using that network.

DS: So going back to our phone example, if 10% of my businesses and people that I need to communicate now use a phone, it’s going to be worth it for me to buy that phone, because I’ll spend a certain amount of the phone with a certain amount of the network. But I’ll save much more by reducing my use of your carrier pigeons by 10%. This dynamic of network effects and the exponentially increasing level of value, leading to an exponentially increasing rate of adoption, and turn driving an even greater level of value, and so on and so forth, creates a positive feedback loop. And any type of digital solution, especially in global trade, needs to embrace and enable network effects.

As I said earlier, the three key requirements for enabling network effects and network effects are dependent on global scale and mass adoption. So this is something that you’ll see us come back to quite a bit. Right now, the majority of the people on the planet still use paper invoices. And if you’re the only person in the world with an invoicing network, despite invoicing being much faster, much more secure, and much more efficient than paper invoices, their value is quite limited because the adoption is so low, so you still need to rely on paper. And because your invoicing network can only communicate with a small number of counter parties that you trade with, its value is very limited. But if 95% of the people on the planet still use that same in wasting network, then that NYC network would be the new paper invoice – there would be no question about whether or not you use that invoicing network.

These same dynamics are really important for any technology solution hoping to digitise and connect trade to play off of and the requirements those technologies must meet in order to drive network effects are all dependent on global scale and mass adoption.

The Evolution of Networks and Platforms

DP: How do you see the evolution of different networks, consortia and platforms?

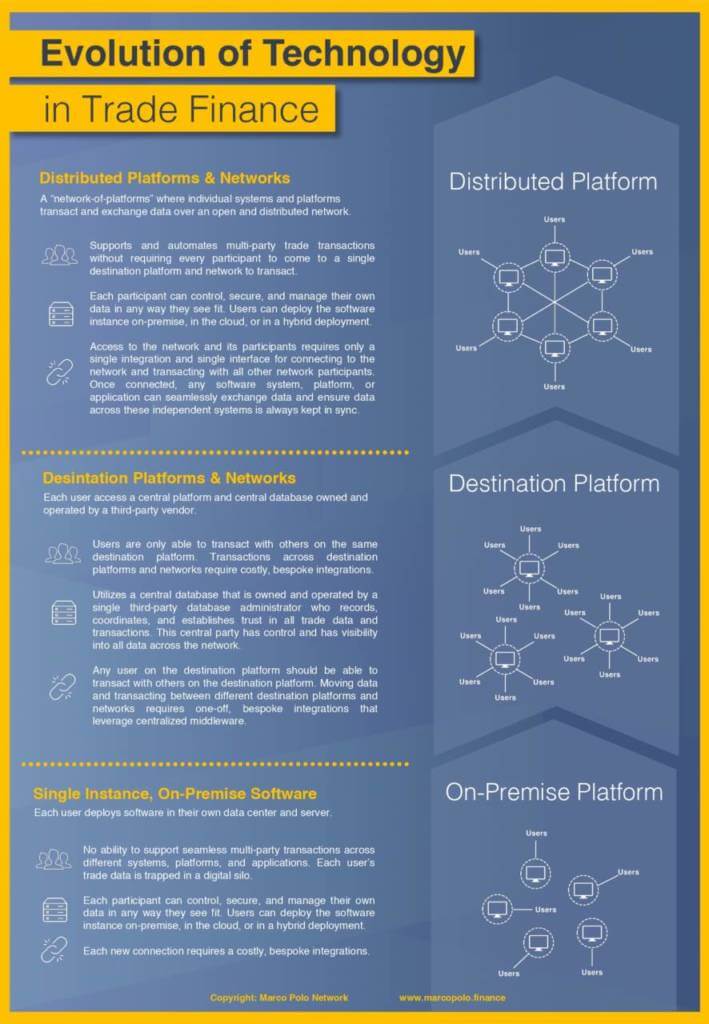

DS: Until now, we’ve experienced three big paradigms of technology that we’ve used to support our efforts to digitise and connect global trade. The first paradigm, which was really the only paradigm up until the early 2000s, was on-premise software and on-premise software instances. The second paradigm, which came about in the early 2000s, and really is still a dominant paradigm today, was our destination networks and platforms. The third paradigm, which we’re discussing here today, is the only paradigm that can be all three of these requirements simultaneously, namely, distributed platforms and networks.

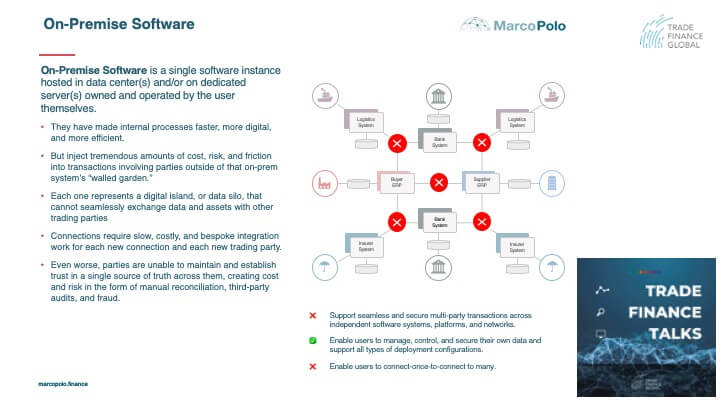

So the first paradigm on premise software, on premise software is a single software instance that’s hosted in the data centre or centres of the user itself. The user is given software that’s either deployed, or developed by a third party or in house. That user is responsible for managing that instance of the software system in its own data centre on its own dedicated servers. These on-premise software systems have made internal processes faster, more digital and more efficient. The issue is, when it is time to move data and support transaction, they inject a tremendous amount of costs, and a tremendous amount of risk and friction into transactions. That’s because each on-premise software instance is really a total digital island or, in other words, a ‘data silo’. That means that each individual instance has no easy way of seamlessly exchanging data and assets with other software systems and the other trading parties that are using those software systems.

If you want to connect these independent digital islands or ‘data silos’, you’re going to need to undertake very slow, very costly and entirely bespoke integration efforts for each new connection, and for each new trading party that you want to exchange data and transact with. This means that for a number of participants you need to transact with, you need to undergo a number of these very slow, costly and bespoke integrations. Which is a huge barrier and a huge undertaking that cannot be underestimated.

The parties that are connected are unable to maintain and establish trust in a single source of truth across that. The messaging systems that these on-premise software systems utilise are really just sending messages that are a reflection of the past. And there’s no guarantee that the software systems involved in that connection or in that network, are looking at the same source of truth and have the same view of the world. As such, there’s no way to ensure that all data across these systems is in sync; the inability to do this creates a ton of cost and a ton of risk in the form of mail reconciliation and third-party audits.

In many instances, the lack of this capability is what makes fraud possible. So when we look at the three requirements, as applied to on-premise software, we see the first requirement is the ability to support seamless and secure multi party trade transactions across different systems and different platforms and networks. For the second requirement, it does mean that on-premise software systems provide users the ability to manage, control and secure their own data. They do that inherently because each user there is managing and hosting this application on their own servers and in data centres behind their firewall. So they physically control that data, and they physically control the hardware on that data. The importance of the second requirement, is really the primary reason why on-premise software is still used today, despite how inefficient and costly it is, because it does still meet that second requirement.

When we look at the next paradigm, we see that it makes the first requirement easier, but eliminates the second. So the last requirement for on-premise software, the ability to connect, is definitely not met by on-premise software. Every new connection, every new trading party, every new technology system that you want to move data from your system to theirs is completely bespoke, completely new integration that must be undertaken every time.

Destination Platforms versus Centralised Software Systems

DP: So what about on-premise software, what’s a destination platform and why can’t trade just use one centralised software system?

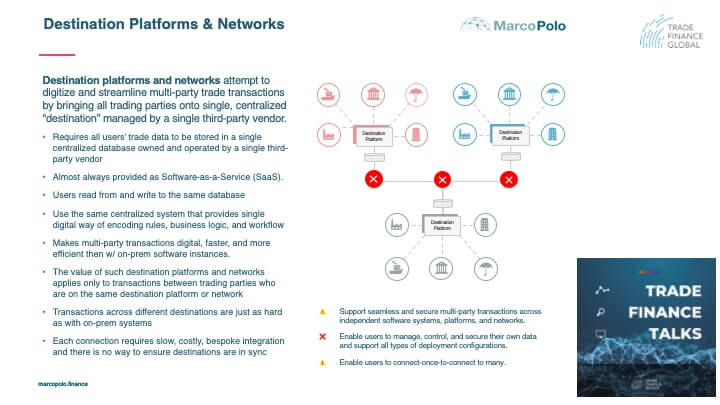

DS: Yeah, so when we talk about an on-premise software, and a lot of the issues that on-premise software has when it comes to multi-party trade transactions, moving data between multiple systems and how hard that is with on-premise software, in the early 2000s, a new paradigm emerges that was designed to address the shortcomings of the first paradigm. And that new paradigm is called a destination platform, or a destination network.

And they attempted to digitize and streamline multi party trade transactions by bringing all parties onto a single centralized destination. That’s managed by a single third party vendor. And these destinations require all users trade data to be stored in a single centralized database and use a single software system that’s owned and operated by a single third party vendor. And because of this, they’re almost always provided software as a service. And because users read and write from the same database, and they use a single software system that provides a standard digital way of encoding rules and business logic and workflow and to trade transactions, this theoretically makes multi party transactions much more digital much faster and more efficient than they were with on premise software systems. And moreover, because everyone uses the same database, we do have an assurance that at least within that destination platform, that everyone’s looking at the same source of truth, and that the errors and and consistencies and fraud that that’s possible and disconnected databases, as is the case and on prem software is mitigated to an extent the issue is one the logical conclusion of a destination platform.

And the basis for its value applies only to transactions between trading parties who are on the same destination platform. So the value that’s derived from reading and writing from the same database, and using the same software system to process transactions is completely done away with when you start to try to move data between different destination platforms.

So when you have trading parties who are using different destination platforms, moving data between them, and and supporting secure multi party trade transactions, is just as hard as it would be with on premise software. And that’s because each new connection between each new destination platform requires the same slow, costly and bespoke integration, and has no way of ensuring that the databases across different destination platforms are in sync. And this is a fatal flaw, because the logical outcome of a destination platform and its ability to actually digitize and connect trade would require all trading parties across the world to store all their trade data in a single database that’s owned by a single third party. And there are thousands of different destination platforms on the market today. And so we see that this is just not possible. And the reason it’s not possible. And the reason there’s been no one platform to rule them all, if you will, is because destination platforms and networks can’t meet all three of these key requirements. The first requirement supporting seamless and secure multi party trade transactions across independent systems. It does not mean it needs for trading parties are using the same destination platform. But it does not meet that requirement for moving data across different destination platforms. Meaning unless as we said, Everyone comes to the same destination and uses a single database, a single software system, this requirement, Canton won’t be met by destination platforms.

The second requirement is one of the reasons and destination platforms failure to meet the second argument as one of the primary reasons why the logical outcome of a destination platform can ever be met. And that’s because it fails to provide users the right not the obligation to manage and control and secure their own data. And that’s because the value of a destination platform is that everyone uses the same database. And that database is maintained and controlled by a third party. So there’s no possible way for a destination platform to need all the data custody data residency and data privacy requirements that you’d see in a global supply chain, and which could have hundreds of thousands of participants. And that’s just one global supply chain. So in order to meet the requirements of millions of different participants in global trade, each participant needs to have the ability to manage and secure the data in any way they see fit so that they can meet both regulatory data costs, the residency and privacy requirements as well as organizational requirements.

And destination platforms. Just can’t do this because of the way they’re built. And it’s unfortunate, but the way that they’re built is how they derive their value. So these destination platforms you see run into really hard moments when they go to scale, because they can’t meet these first two requirements. The third requirement, again, is the ability to connect wants to connect to many destination platforms can meet that or trading parties on the same destination trading platform or network. If I connect to one destination, once I’m theoretically connected to all other trading parties on that same platform, again, the issue is there are thousands of these destination platforms. And we already know and an established that there can never be one to rule them all. And so really, you don’t have Connect wants to connect too many because there’s no way to connect to one destination platform, but then also be seamlessly connected to everyone else on every other destination platform. So in reality, you run into the same exact issues you do with on-premise software. Almost every new connection that you need to make requires a very bespoke, and costly and time-consuming integration effort.

Distributed Platforms and Networks

DP: So, tell us about distributed platforms and networks – what are they, and what can they do?

DS: When we talk about an on-premise software, and a lot of the issues that on-premise software has when it comes to multi-party trade transactions, moving data between multiple systems and how hard that is with on premise software, in the early 2000s, a new paradigm emerged that was designed to address the shortcomings of the first paradigm. And that new paradigm is called a destination platform, or a destination network.

They attempted to digitise and streamline multi-party trade transactions by bringing all parties onto a single centralised destination that’s managed by a single third-party vendor. And these destinations require all users that trade data to be stored in a single centralised database and use a single software system that’s owned and operated by a single third-party vendor. And because of this, they’re almost always providing software as a service. Because users read and write from the same database, and they use a single software system that provides a standard digital way of encoding rules and business logic and workflow and to trade transactions, this theoretically makes multi-party transactions much more digital, much faster, and more efficient than they were with on-premise software systems. Moreover, because everyone uses the same database, we do have an assurance that, at least within that destination platform, that everyone’s looking at the same source of truth, so the errors and consistencies and fraud that’s possible within disconnected databases, is mitigated to an extent.

The basis for its value applies only to transactions between trading parties who are on the same destination platform. So the value that’s derived from reading and writing from the same database, and using the same software system to process transactions is completely done away with when you start to try to move data between different destination platforms.

When you have trading parties who are using different destination platforms and moving data between them, as well as supporting secure multi-party trade transactions, it is just as hard as it would be with on-premise software. That’s because each new connection between each new destination platform requires the same slow, costly and bespoke integration, and has no way of ensuring that the databases across different destination platforms are in sync. And this is a fatal flaw, because the logical outcome of a destination platform and its ability to actually digitise and connect trade would require all trading parties across the world to store all their trade data in a single database that’s owned by a single third party. There are thousands of different destination platforms on the market today, so we can see that this is just not possible. The reason there’s been no one platform to rule them all, if you will, is because destination platforms and networks can’t meet all three of the aforementioned key requirements. Unless everyone comes to the same destination and uses a single database, a single software system, this requirement won’t be met by destination platforms.

The second requirement is one of the reasons destination platforms fail to meet the second argument. It fails to provide users the right, but not the obligation, to manage and control and secure their own data. Because the value of a destination platform is that everyone uses the same database and that database is maintained and controlled by a third party, means there is no possible way for a destination platform to meet all the data custody data residency and data privacy requirements that you’d see in a global supply chain, which could have hundreds of thousands of participants. So, in order to meet the requirements of millions of different participants in global trade, each participant needs to have the ability to manage and secure the data in any way they see fit so that they can meet both regulatory data costs, the residency and privacy requirements, as well as organisational requirements.

Destination platforms just can’t do this because of the way they’re built. It’s unfortunate, but the way they’re built is how they derive their value. So these destination platforms you see run into really hard moments when they go to scale, because they can’t meet these first two requirements. The third requirement, again, is the ability to connect to many destination platforms on the same destination trading platform or network. If I connect to one destination once, I’m theoretically connected to all other trading parties on that same platform, but again, the issue is there are thousands of these destination platforms – we have already established that there can never be one to rule them all. So really, you don’t want to connect too many because there’s no way to connect to one destination platform, but then also be seamlessly connected to everyone else on every other destination platform. In reality, you run into the same exact issues you do with on-premise software. Almost each new connection that you need to make requires a very bespoke, and costly and time-consuming integration effort.

The Future of Networks and Trade

DP: Very interesting Dave, thank you. So now, final question for today, which trade paradigm or network in your thoughts will prevail in the future?

DS: One of the primary purposes of this article was really to answer that question and, more importantly, which platform or network could also possibly achieve our goal of a truly digital and truly connected global trade ecosystem. It’s too early to say with complete certainty that distributed trade networks and platforms will in fact lead to a ubiquitously digital and ubiquitously connected global trade ecosystem. Strong network effects are required, and superior technology does not guarantee them.

There are also other factors at play which are not related to technology, including, but not limited to, legal and regulatory considerations. Factors such as job preservation bias; the difficulty of aligning incentives between all the key stakeholders and all the different industries around the world; and entrenched cultural and institutional habits and comforts that have been built up over hundreds of years. These factors cannot be ignored and need to be addressed with any and all digitisation and connectivity efforts. What we can say with complete certainty, backed by decades of empirical evidence, is that the first two paradigms cannot digitise and connect global trade. They do not – and cannot – meet all three key aims simultaneously. On the other hand, distributed trade networks and platforms can meet all three requirements simultaneously. So if we really do believe that a global trade ecosystem that is digital and connected in a ubiquitous manner, one that has all the scale and all the mass adoption that we need to drive network effects, then we need to understand those first two paradigms and try to use technology to do that. Creating distributed trade platforms and networks by meeting all three requirements simultaneously, provides us with the basis for a real effort that has a shot of being successful to digitise and connect global trade.

DP: Thank you very much for joining us on Trade Finance Talks, and we really look forward to hearing you at Consortia 2019 later on today! For our listeners, make sure you check out our map of the consortia, who’s who in the network, and you can download our guides, infographics and much more on test.tfg.pixelfield.dev/blockchain.