Listen to this podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Podbean, Podtail, ListenNotes, TuneIn

- According to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), “Trade-based money laundering (TBML) is a form of ‘white collar crime’ that involves tragic human costs and consequences, which is massively underestimated and underreported.”

- It’s extremely hard to detect and comes at significant cost.

- This initiative demonstrates how improving reporting mechanisms can help combat TBML.

TBML is conducted by criminals to conceal illegal income by moving it through legitimate trade transactions by undervaluing or overvaluing goods and services, thus laundering large sums of money.

Determining the global scale of TBML is challenging as the data is dispersed across agencies. Financial intelligence units (FIUs) see the financial information related to trade, while customs organisations inspect the physical goods themselves, as well as trade documents. TBML data is also dispersed across borders given that the movement of value involves two or more countries.

Therefore, the exact global scale of TBML is uncertain. However, estimates based on the import-export value gap from the think tank Global Financial Integrity suggest that the figure reached $8.7 trillion between 2008 and 2017.

Despite its severity, TBML all around the world often flies under authorities’ radar.

However, international organisations and financial institutions are beginning to confront this threat head-on. Through data-driven initiatives, capacity building, and collaboration, they are developing solutions to detect and prevent TBML.

To learn more about TBML and the fight against it, Mahika Ravi Shankar, Assistant Editor at Trade Finance Global (TFG), spoke with Catherine Estrada from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and Sumera Baloch from Pakistan’s Financial Monitoring Unit (FMU).

The global impact of TBML

What makes TBML particularly dangerous is its subtlety; laundered money is often hidden within legitimate trade flows, making it difficult for authorities to distinguish between lawful commerce and illegal activity.

Criminals may undervalue or overvalue goods, falsify documents, or create phantom shipments, making an illegitimate transaction seem ordinary. By definition, global trade means financial flows cross multiple jurisdictions, making the problem more complex and difficult to trace.

Despite the risks, TBML is underreported, largely due to a lack of awareness and insufficient reporting mechanisms in place. The economic damage of such crimes can be significant, eroding trust in global trade systems and financing illegal activities such as terrorism, human trafficking, and drug smuggling. Addressing this requires international cooperation, as no country can combat TBML alone.

Estrada said, “If we want to be comfortable in continuing to support trade in our member countries, we need to make people more aware of TBML risks.”

Detecting TBML is challenging without a unified effort to report suspicious trade transactions. International organisations and financial institutions have a crucial role to play in recognising TBML and developing tools and methodologies to prevent it from undermining the integrity of global trade.

ADB’s Trade and Supply Chain Finance Program (TSCFP) pilot initiative

The ADB’s TSCFP has taken a proactive approach to tackling TBML challenges.

Estrada said, “The main goal of the TSCFP is to help close financing gaps, but one barrier to financing is the stringent anti-money laundering (AML) and combating the financing of terrorism (CFT) requirements, which often results in the rejection of proposals.”

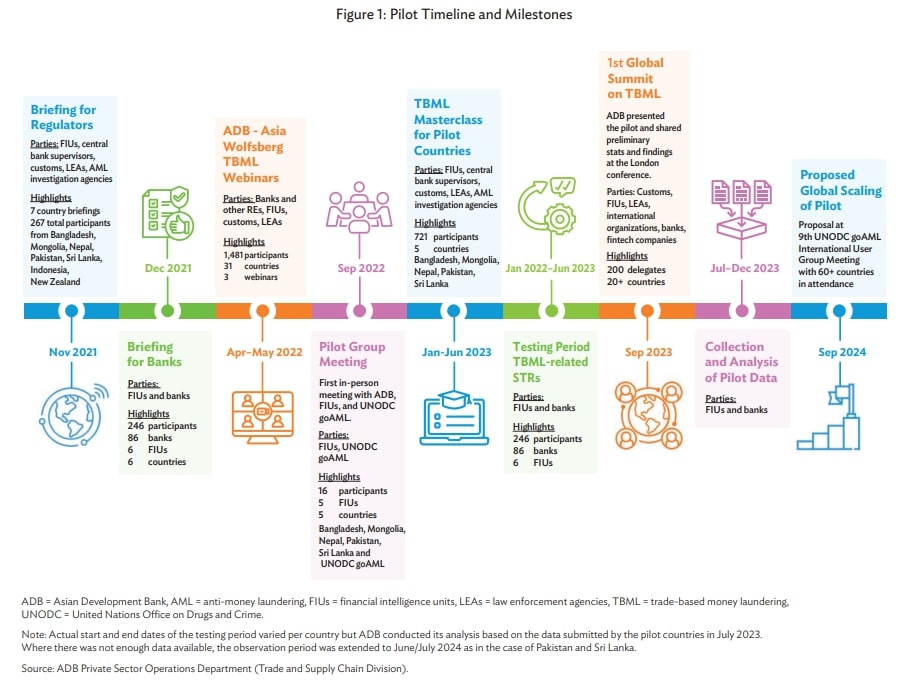

Recognising that financial institutions hold vast amounts of data that could be useful in identifying TBML activities, ADB launched a pilot initiative, partnering with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and financial intelligence units (FIUs) from five Asian countries. The goal was to enhance the existing reporting structure for suspicious transaction reports (STRs) by integrating new trade-related data elements.

STRs are critical tools in countering TBML, but they are not designed to capture the intelligence-rich data available in trade transactions, such as information about the trading parties, the goods, and the cargo route.

Recognising this, ADB designed and implemented a pilot to enhance TBML detection by adding data elements that can be extracted from trade financing transactions, thereby creating STRs more tailored to trade.

Baloch said, “With the pilot run, banks started appreciating the importance of reporting detailed information in TBML-related STRs, and the number of these reports increased due to the new goAML STR-T format introduced. The pilot project was an opportunity for us to sensitise banks to the importance of capturing detailed TBML data in the STRs.”

This pilot, which ran from January 2022 to June 2023, introduced a more detailed approach to STRs, which had previously lacked the specific data needed to identify TBML activities. By adding relevant trade data, such as information about the goods and services being traded, ADB and its partners aimed to make these reports more effective in detecting illicit activity.

The initiative relied on goAML, an integrated software developed by the UNODC, used by FIUs to collect and analyse financial intelligence.

The pilot’s results were promising. There was an increase in the quality and quantity of STRs reported without adding significant burdens to financial institutions, as the required data was already collected during regular trade transactions.

The enhancement lay in organising and labelling the data in a way that made it easier for FIUs to identify and analyse TBML-specific reports.

Capacity building and cross-sector collaboration

From the outset of the ADB pilot, it was clear that banks alone could not combat TBML. What was needed was an ecosystem approach, bringing together the public and private sectors, including banks, FIUs, customs officials, and law enforcement.

Each of these entities holds a piece of the puzzle; by working together, they can uncover TBML activities that might otherwise go unnoticed.

A critical element of this collaboration is capacity building.

Estrade said, “We know that criminals are constantly innovating in how they exploit trade to launder money, so we need to continuously train stakeholders. We organised roundtables where the public and private sectors discussed challenges and potential solutions specific to AML/CFT issues in trade.”

These conferences, organised in key locations like Pakistan, provided a platform for financial institutions and law enforcement to exchange ideas and learn from one another, helping to enhance the understanding of TBML and improve reporting mechanisms.

Baloch said, “After the pilot launch and conferences, we saw banks start to conduct their own in-house training sessions to improve their knowledge on TBML and reporting practices.”

This collaborative nature ensured that no single sector was left to tackle TBML alone. The partnership between the public and private sectors brought the kind of multi-sector cooperation needed for any meaningful progress in the fight against TBML.

Global rollout and potential for replication

The results of the pilot were promising.

In Bangladesh, which holds a notable position globally in the use of letters of credit (LCs) given its import-heavy economy, the FIU reported a 148% increase in the number of TBML-related STRs reported by banks during the pilot.

In Nepal, there was no TBML-related STRs identified pre-pilot because because the concept of specific reporting for TBML did not exist. Post-pilot in Nepal, the FIU recorded 14 TBML-related STRs in a short period. The FIU values the pilot for enabling the integration of TBML risks into the country’s Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) national risk assessment.

According to the ADB report, “The pilot introduced new trade-related data elements into STRs, resulting in countries reporting a significant increase in the number of suspicious trade transactions and higher-quality information that could translate into increased investigations of potential TBML cases.”

Estrada said, “We are working toward encouraging a global rollout because the results of the pilot have shown that this approach can be replicated across countries.”

Since the initiative builds on existing reporting structures and widely adopted software like GoAML, which more than 70 countries already use, the program can be rolled out easily in these jurisdictions.

The data enhancements made to STRs in the pilot programme are relevant to any country that engages in international trade, making it an adaptable solution for TBML detection.

Estrada added, “We presented the pilot results at the UNODC goAML International User Group meeting, and we encouraged over 50 countries to adopt the enhanced STR framework.”

With strong partnerships developed during the pilot, ADB hopes to expand the initiative to more regions, sharing the knowledge and results from the pilot programme with other FIUs and financial institutions worldwide.

Baloch said, “International collaboration is crucial because these crimes are transnational, and the flow of illicit funds across borders is becoming easier.”

TBML thrives in the complexity of international trade, making it difficult for authorities to track illicit activities. However, initiatives like ADB’s TSCFP pilot, in collaboration with the UNODC and FIUs, demonstrate that progress can be made in detecting and preventing TBML through enhanced data reporting, capacity building, and collaboration.

By creating a more practical and efficient reporting structure, leveraging existing data, and encouraging cross-sector collaboration, international organisations and financial institutions are taking meaningful steps toward combating TBML.

The success of the pilot programme in five countries highlights the potential for a global rollout, which could revolutionise the fight against trade-based money laundering.

As more countries adopt these enhanced measures, the global financial system will be better equipped to disrupt illicit trade activities and secure the flow of legitimate commerce.