The $1.2 Trillion initiative is promoting regionalism by means of investments in infrastructural development, an opportunity which China can exercise to influence beyond countries’ foreign policy choices. Why is there a necessity of macroeconomic policy coordination and how China perceives them as a bridgehead to the EU market and a crucial transit corridor to its supply chains?

What is OBOR?

One Belt One Road (OBOR), the brainchild of Chinese President Xi Jinping, is an ambitious economic development and commercial project that focuses on improving connectivity and cooperation among multiple countries spread across the continents of Asia, Africa, and Europe. Dubbed as the “Project of the Century” by the Chinese authorities, OBOR spans about 78 countries.

Where is it at so far?

In the beginning, the initiative started with the 16+1 sub-regional cooperation format brought together China and most of the former communist countries of the region, including 11 EU member states (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Slovenia, Croatia) and 5 Balkan countries (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia). In 2018, Greece became a full member of this grouping, turning it into 17+1 cooperation mechanism. It is worth noting that so far Belarus and Ukraine have not been invited to cooperate under the 17+1 initiative. Perhaps the reason is that China recognises these countries as an area of Russian influence. In turn, in the case of the Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, China perceives them as a bridgehead to the EU market and a crucial transit corridor within the OBOR towards Western Europe supply chains.

Opportunities within Balkan

One of the most important part of the OBOR in Europe is its Balkan part. New Silk Road on the Balkans starts in Greece and goes through Macedonia and Serbia to Hungary. China is now combining its vast economic resources with a muscular presence on the global stage.[1] It is, to a large extend, the outcome of Chinas’ ‘open door’ policy expression of a foreign policy agenda aiming at increasing commercial ties, through improvement of infrastructural connections, specifically in relation to overland the maritime transport infrastructure corridors.

Key trade information from key markets

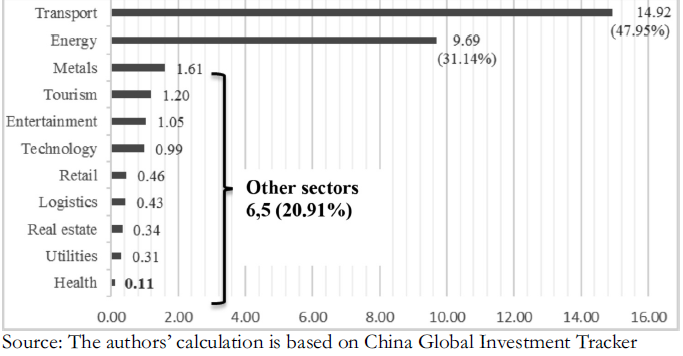

As globalization and regional economic integration progress, oceans have become a foundation and bridge for market and technological cooperation and for information sharing. China supports the Silk Road Spirit – “peace and cooperation, openness and inclusiveness, mutual learning and mutual benefit”, and exerts efforts to implement the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in the field of coasts and oceans. China is willing to work closely with countries along the Road, engage in all dimensional and broad scoped maritime cooperation with cooperation platforms and establish a constructive and pragmatic Blue Partnership to create a “blue engine” for sustainability.[2] The below chart demonstrates the investment sectors which the project will focus and as concluded China will be investing in heavy infrastructural projects.

Why policy is needed?

The geographic expanse covered by the initiative includes many nations with levels of corruption. Traditionally Chinese companies being less transparent that their international competitors and Beijing’s intensity to curb bribery and corporate malfeasance limited to its domestic economy, a massive inflow of Chinese funds into countries with weak governance is likely to boost ongoing corruption. Given that some projects are linked to geopolitical objectives, like gaining control over assets with military uses, Beijing may well manipulate political elites to look favorably on its offers. From the above we determine the necessity of macroeconomic policy coordination.[3]

Five Pillar Policies

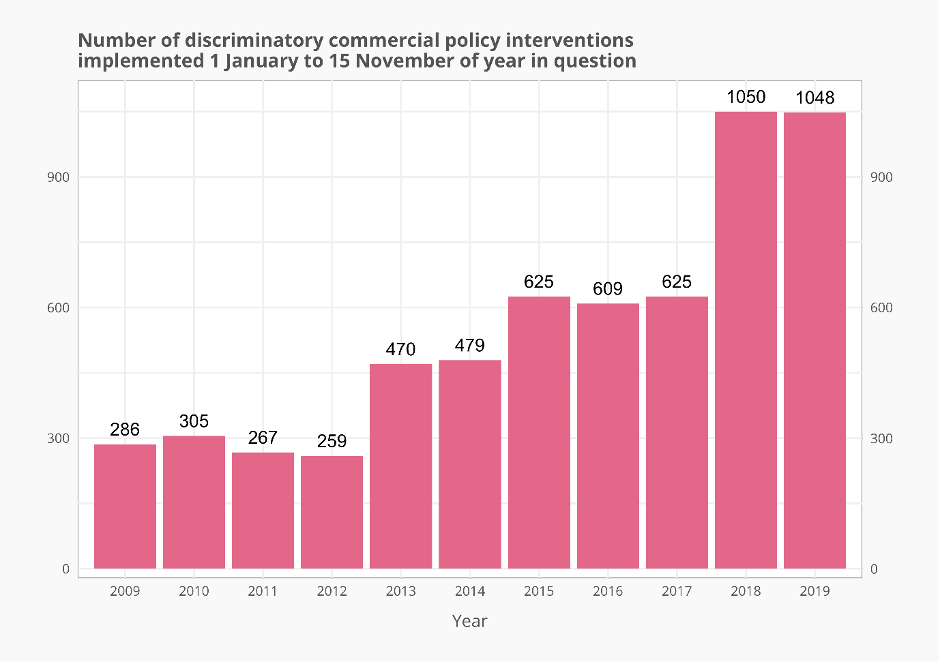

The magnitude and complexity of the OBOR project creates numerous policy challenges for countries in the region seeking to benefit from its implementation. These challenges are significant, ranging from a critical assessment of the project’s objectives, the process of stakeholder inclusion, regulatory capacity-building and trade co-financing requirements. Such policy challenges require advisory services and institutional guidance from international organizations such as EBRD which is familiar with the host country and capable of interpreting the challenges and opportunities of the Chinese initiatives. Counting the EU as one, a total of 15 governments enacted policies that distorted more than $10 billion of trade on 73 occasions during the Populist era. President Trump’s trade wars and foreign reaction to them were responsible for ‘only’ 14 instances of such jumbo protectionism.

1. Policy Coordination

Ministries, regulatory agencies and municipalities subject to investment initiatives within the framework of the OBOR project are frequently overstretched regarding the licensing requirements, financial implications, zoning regulations and European Union legal obligations that encompass cooperation with Chinese counterparties. In cooperation with institutions such as the EU Delegations, there will be easier compliance to projects which require compliance with environmental standards in that extend.

2. Financial Integration

An area of strategic trade policy dialogue concerns the lending practices of Chinese banks. Trade Structured loans offered to EU counterparties reduce or even abolish the need for co-financing. This business practice affects banks’ lending policies, including the subsequent tendering process with local authorities, pricing levels and transparency requirements. It is crucial and required capital markets to be supported in all structural changes in the real development levels including technological developments aiming a common purpose.

3. Trade Facilitation

As the OBOR project is more about trade expansion, the Trade Facilitation programme should make full use of its opportunities in the countries of operation. This could include guarantees to commercial banks concerning payment risk of trade transactions. The banking sector involved is crucial to offer guarantees in line with the memorandum of understanding signed between those countries. The existing 17+1 format focuses on investments and the willingness of countries in central, eastern and south-eastern Europe to expand trade cooperation with China.

4. People to People Exchanges

The existing business model of Chinese companies active in the region is hardly supportive of the local economy. Providing lending and foreign workers bypasses domestic banks as well as local expertise on the ground. In this respect, even concessional lending by Chinese banks, frequently praised for its lower costs, may in fact not be as cheap without spill over effects materializing on the local economy. The more infrastructure projects along the OBOR take root, the more people and businesses have opportunities to be connected.

5. Investment Dependency

The final field of engagement in policy dialogue concerns a critical assessment of the project in terms of establishing Investment Dependency for countries in the region. Medium to long term growth perspectives in individual countries subject to the OBOR are at risk of excessive dependence on Chinese state investment. Chinese authorities should balance the investment plans for business within their country and their subsidiaries in EU Trade Region as well.

ARTICLE: Global overview on US-China tensions, the BRI effect, and Europe’s digitisation projects

Securing investments in a region of extreme geopolitical volatility will be a tough test for China’s foreign policy in the coming years. China does not have an overall strategy regarding the Mediterranean Trade region’s affairs. Instead, Beijing prefers to deal with each country bilaterally. The policy towards the EU region is still dominated by economic factors, particularly trade and investment. Beijing will have to forgo strict compliance with its principle of noninterference if it wants to earn the appropriate benefits. For the time being, however, this process is hardly visible, since China’s behavior in the EU region is cautious, aimed at keeping a low profile, and does not seek to significantly alter existing dynamics. China prefers to act wisely and to avoid being involved in confrontations in the region. Whether this approach fulfills Beijing’s One Belt, One Road dream, however, remains to be seen. The question is in the pace and the scope of this process. The distance between geographical, economic, social and cultural will continue to be relevant only in the short term.

Now launched! Summer Edition 2020

Trade Finance Global’s latest edition of Trade Finance Talks is now out!

This summer 2020 edition, entitled ‘Coronavirus & The Fourth Industrial Revolution’, is available for free online, covering the latest in trade, export credit insurance, receivables and supply chain, with special features on fintech and digitisation.