For most farmers their main objective is to intensify crop yields to ensure that they meet their financial obligations and remain somewhat profitable despite erratic weather conditions by using pesticides and synthetic agrochemicals even though science warns that this approach will lead to their demise tomorrow.

Southern African farming challenges

Southern Africa has small, medium and large commercial farmers. Notably smallholder farms form an estimated 80% of all farms in the region and as result small and medium farmers produce the majority of the crops. The SME yields are purchased by large commercial farms and millers as farmgate in local markets.

Low rainfall and unrelenting heat in the region have resulted in reduced crop yields. In 2019 Zambia’s maize harvest fell to 2million metric tonnes compared to 3.6 million in 2017. The decrease in supply increased prices and widened the food security gap.

Farmers are losing money regardless of their size, defaulting on existing facilities, and as such financiers are exiting structured commodity finance due to credit and compliance risks. Farmers desperately trying to increase their yields have resorted to using more agrochemicals to maintain productivity however this increases their input costs resulting in more debt.

Southern African farmers will continue seeing the inconsistencies in their yield for years to come as long as the extreme weather patterns continue, and agricultural risks increase unless they review and change the current model.

Commodity Finance Structures and Challenges

WEF stated that 80 – 90% of global trade relies on trade finance but it is estimated that $1.5 trillion of trade finance applications are rejected. The trade finance rejection rate for requests in Africa exceeds 50% and this mainly consists of small and medium farmers.

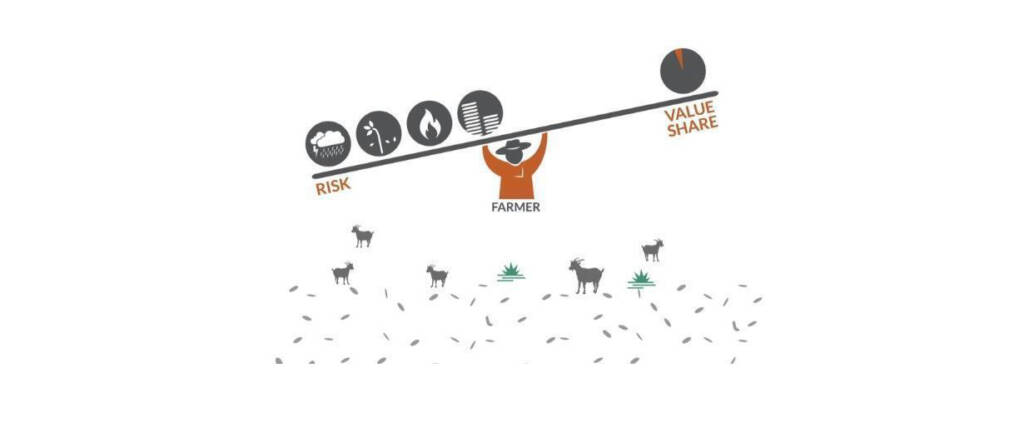

SMEs produce more crops than commercial farmers but cannot access financing due to the risks they face which include irregular cash flows, systemic risks to floods, droughts and plant disease and lack of collateral. Finance is critical for SME farmers to invest in productivity and to enable better access to markets to sell their crops.

Starved for funding and struggling with a fragmented value chain, small and most medium farmers sell their crops at local markets with an exception of a few that have off-taker contracts with processors and retailers.

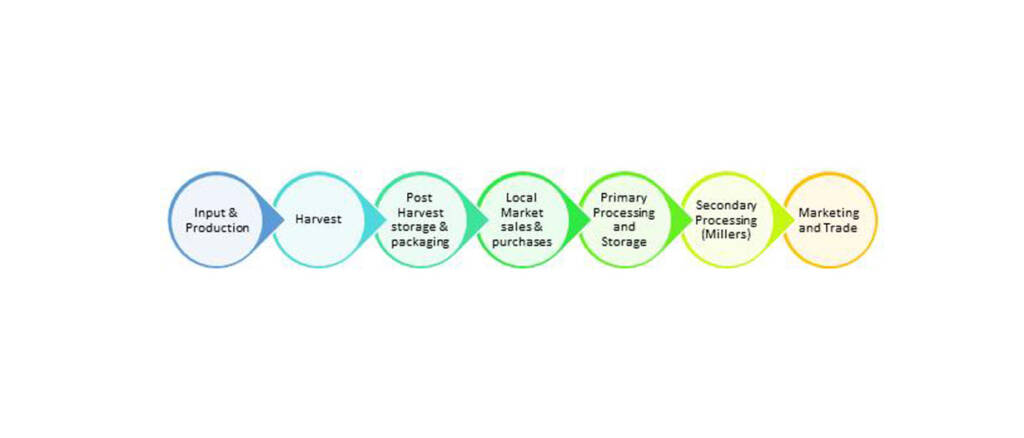

For the value chain above, SME Commodity Finance Facility would be structured as following dependent on affordability and working capital funding gap:

- Input Invoice Financing for 180 Days: facilitates the purchase of agrochemicals, seeds pesticides and synthetic fertilisers during sowing and production. The advance rate can vary from 100% to 75% of the invoice amount. To avoid misappropriation of funds, disbursements are directly to suppliers.

- Warehouse Receipt Finance for 90 Days: The purpose of the facility is financing crops in storage after harvest, farmgate crop purchases. The crops are pledged to the lender as security in case of default. Lenders require a collateral manager to monitor the crops received into lender approved storage by issuance of warehouse receipt and quality certificate with weekly reporting noting any changes. Advance rates vary, during the tenor commodity price movements are monitored. Any shortfalls in the finance price vs the current must be settled by the borrower. The loan proceeds are either paid directly into the borrowers account or settle the input finance exposure.

- Export Invoice Financing for 60 Days: The purpose is to fund export invoice receivables once the product has been sold to off-takers be it millers or retailers. Advance rates are usually a portion of the invoice value. Loan proceeds settle Warehouse Receipt Finance exposure.

In a perfect world, the above structure would work seamlessly however this is not the case. Extreme drought and heat result in either crop failure or reduced yield. This unfortunately leads to farmers defaulting on their facilities and further sinking into debt. In the past some farmers resorted to selling their properties to inject capital into their business and improve their liquidity.

Whilst there is a global call for financial institutions to include climate science reasoning in lending decisions. Banks in developing countries are facing challenges when it comes to integrating climate risk into their trade finance portfolios due to inadequate regional climate science information and portfolio-level climate data.

The Solution is Regenerative Farming

Regenerative farming is the solution to both the soil degradation caused by agrochemicals, withstanding droughts as well as increasing crop yields in the long run and saving on input costs. It is noted that it can take up to three years for the soil to recover with little to no production halting revenue streams.

It has been proven that regenerative practices work by farmers who have tried it. WEF mentioned that Malawi and some parts of Zambia where farmers have mixed crops, their maize yields grew up to 400% of the national average.

Regenerative Farming

Regenerative farming and/or agroforestry is basically allowing agriculture to sustain itself as it once did with its crops, trees, plants and livestock. This model balances and restores natural soil nutrients and resiliency and will stop farmers’ dependency on synthetic agrochemicals.

“The agricultural risks are managed as farmers have access to wider regenerative practices and can choose which approach works best for their land.” – Grounded

While some farmers are still very hesitant and nervous about low production years while the soil recovers which can be two to three years. Others have acknowledged the limits within the conventional agricultural model noting soil nutrients are depleted. They have jumped ship and adopted the regenerative model, granted they could afford to, and their decisions have paid off.

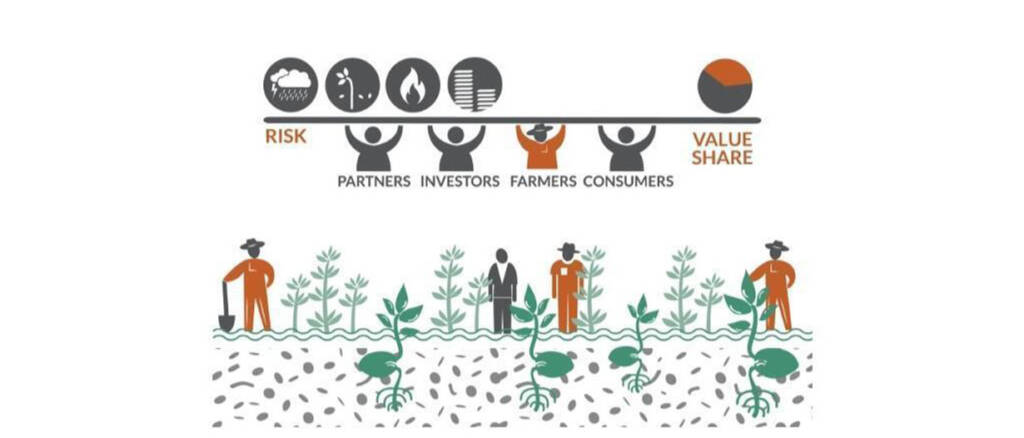

In the banking sector, Rabobank has teamed up with UNEP, Dutch Development Bank and IDH, The Sustainable Trade Initiative to develop the Agri3 Fund to help finance the transition period or soil recovery period to the first yield. The fund was created to mobilize $1billion towards sustainable agriculture, prevention of deforestation and improving rural livelihoods.

Hans Loth stated that:

“Farming is perceived by many as risky, not many commercial banks lend to farmers. They do not like the cyclical nature. We, however, understand the risks as we’ve been in the business a long time – but even we have risk appetite challenges around demand for loans at longer tenor to allow for the transition periods.”

Agri3 Fund’s first disbursement was scheduled for the first quarter of 2020, unfortunately due to COVID19 we are unable to track progress thereof.

As you might have guessed the Agri3 Fund will most likely help a handful, leaving small scale farmers stranded once again as their balance sheets are not as strong anymore.

Due to the financial pressures, some farmers have opted for private investment firms particularly in the US to fund their transition phase. This is mainly due to stringent lending terms and conditions from financial institutions which are not flexible for farmers or nature and secondly farmers have no collateral to pledge anymore.

While the private finance firms’ approach and due diligence might be like those from banks, they tailor facility conditions to each farmer. The terms and conditions are not cast in stone, they are reviewed and adjusted regularly with each soil survey conducted by scientists checking the progress of soil recovery during the facility tenor.

Private transition finance is still a new concept globally and with more investors looking for green opportunities, it will become a strong contender for the traditional banking sector.

This article was written by a member of TFG’s 2020 International Trade Professionals Programme. Find out more here.

Disclaimer: The views that have been expressed on this page are that of the author, which may or may not be in line with their company, Trade Finance Global or London Institute of Banking and Finance’s view.

Type a message