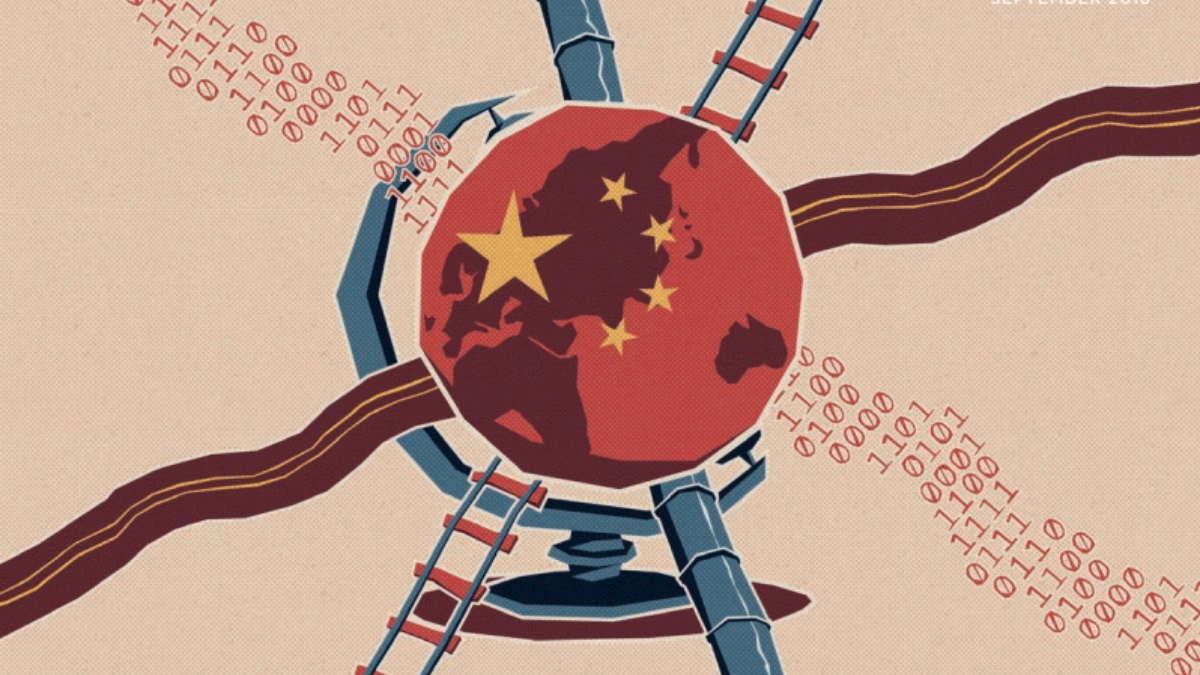

History’s most ambitious and extensive infrastructure project is currently underway. If successful, China will become the world’s undisputed Centrepoint of trade. However, such a triumph will not come easily.

All Roads Lead to Beijing

Elagabalus, a Roman emperor who ruled from AD 218 to 222, is well remembered for his impossibly extravagant wardrobe – he wore clothes made entirely of silk. Nowadays, considering silk a rarity is a puzzling suggestion, but in Roman times the fabric was the height of luxury. Rome enjoyed the benefits of the ancient world’s greatest trade network. Nowhere else was a material from such a distant land available in large enough quantities to fashion an entire wardrobe, and the eponymous silk road was no doubt responsible.

China is seeking to rebuild the silk road. Bringing the concept into the 21st century, president Xi Jinping envisions an overland ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’, and, throughout the South China Sea, Indian Ocean, and stretching northwards into the Mediterranean, a ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road’.

The scale of this project is immense – it will cost multiple trillions of dollars, take years to complete, and require the participation of dozens of countries and international organizations. The ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ or BRI, is China’s way of exporting its economic model to the world, and a key step on its path to becoming a superpower. As time passes, and the project continues to progress, a fundamental understanding of the BRI becomes more and more essential.

How Does the BRI Work?

The BRI is designed to make it easier for other countries to trade with China. Elagabalus got his opulent outfits courtesy of a network of roads from east to west – roads are the fundamental arteries of trade. If China is the heart, then the roads, railways, and seaways of the BRI constitute the country’s circulatory system. The overland, ‘Belt’ part of the Belt and Road Initiative consists of six economic corridors:

- The China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor (CMREC)

- The New Eurasian Land Bridge, a rail link between Asia and Europe

- The China-Central and Western Asia Economic Corridor

- The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)

- The Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor (BCIMEC)

- The China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor

Corridors include highways, railways, and pipelines, and are also dotted with installations such as industrial parks, oil refineries, mines, and power plants. All of these individual infrastructure projects come together to serve one simple purpose: to make it easier to move a higher volume of goods in and out of China more quickly, cheaply, and efficiently. Many of these corridors also meet with the Maritime Silk Road, most notably throughout Southeast Asia, and on the Pakistani coast.

The BRI also gives China an opportunity to further entrench its position in the South China Sea. Always a point of uncertain geopolitical tension, the South China Sea is a key component of the Maritime Silk Road (connecting coastal Chinese cities to ports in the Indian Ocean, Africa, and the Mediterranean), which is itself half the BRI. Natural gas, oil, and fish are some of the commodities that the South China Sea holds, which China will no doubt continue to vie for. Furthermore, a full 30% of global shipping trade runs through those waters.

As of April 2019, 126 countries and 29 international organizations have signed documents affirming BRI-related cooperation with China. The project, though far from complete, is already well underway.

In 2017, the first-ever Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation (BRF) was held, giving an institutional face to the shadowy, multi-trillion-dollar undertaking. The second BRF took place this past April, where the US-China trade war “hijacked” the summit, demonstrating that, despite its long-term and carefully planned nature, the BRI is not immune to the short-term political tumult.

The BRI – Alternate Perspectives

China has gathered so much support for the BRI due to the fact that it promotes participation in the initiative as beneficial to all parties. Indeed, in theory, it sounds fantastic. A network such as the BRI has potential to bring much-needed foreign investment to many developing nations, lift numerous people out of poverty, and the increased volume of trade would boost global GDP – the economic theory bears the project out.

The reality, of course, is muddier. Many critics of the BRI call it a thinly-veiled attempt to advance China’s geopolitical interests. When layered with the US-China trade war, Journalist Michael Vatikiotis points out that the BRI introduces a “polarity” into an otherwise diverse trade ecosystem, forcing countries to align themselves with either Chinese or American interests, which may potentially disrupt supply chains – the very opposite of what the BRI sets out to do.

The BRI is also often demonised for creating a “debt trap”. China has been loaning money for BRI projects to notoriously corrupt and unreliable states, and the worry is that China is well aware of the high likelihood of default – that it’s looking to build a coalition of poor (often authoritarian) states, which can be shackled into Chinese subservience. Though extreme, a move in this direction would not necessarily be off-brand for China.

Finally, the BRI cannot be considered a success unless the extra trade it produces can be financed properly. Access to high-quality resources, infrastructure, and transport does not necessarily translate to access to trade financing services, especially for SMEs. Though DLT and blockchain technology is currently thought to be the key to closing the 1.5 trillion dollar trade finance gap, the technology is not yet mature, and China shouldn’t be banking on it to catch up to the BRI – if China intends to stimulate a vast amount of trade and economic integration, it should be prepared to have a discussion about how to finance that activity.

All this is to say that banks and other providers of trade finance must be included in the construction of the BRI. The long-term nature of the project indicates that thought should be given to current trends – as the graph below shows, Mainland Chinese domestic banks are losing popularity while international and offshore banks are gaining ground. These are the players that should be included in talks at Belt and Road Forums in the future.

Conclusion

A successful Belt and Road Initiative will mean that global trade’s centre of gravity will have shifted away from the US and Europe for the first time in decades. The BRI would be the capstone to the meteoric rise that has characterized China’s economic performance since the end of the second world war. However, it’s much too early to call the battle won. The BRI will take many more years to come to fruition, and will only do so gradually, at great expense. The international community’s reaction will no doubt influence the development of the project, and anything can happen along the way.

China should take care to avoid straining existing relationships as work on the BRI continues; particularly its trade relationship with the west, which may continue to see the BRI as a challenge to its hegemony. Attention should also be paid to the trade financing side of the BRI.

A project of this magnitude could be greatly beneficial to the global economy if key players work together. China needs to learn how to continue with the project in the spirit of fair play. The west, and particularly America, needs to realize that its moment in the sun may be over.