Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

Global trade has shown remarkable robustness in the past few years, even under progressively difficult operational circumstances. While there’s a gradual downturn underway, there are still promising factors.

These involve trade between Global South countries, along with digital services commerce, which might act as robust foundational motivators in the future.

However, geopolitical uncertainties are obstructing trade activities and might pose a growing challenge to the endurance exhibited so far. Central to this issue will be the 2024 in the US, and EU, which are expected to bring about more divided governments, possibly affecting the consistency of trade policies negatively.

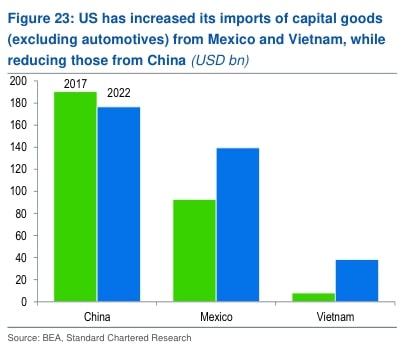

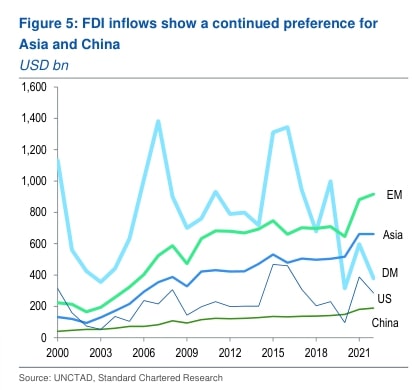

The US’ China “decoupling” policy, while putting a strain on worldwide trade ties, has opened doors for nations like Mexico and Vietnam. Nonetheless, as the strain between Washington and Beijing intensifies, hazards like prohibitions on specific types of Foreign Direct Investment into China keep the outlook unclear. Provocative language might also increase as the US election campaign gears up.

Meanwhile, the EU has adopted its own China policy of “de-risking” by seeking to reduce dependence on, for example, critical raw material imports. However, an increasingly assertive China, as well as the heightening costs of escalating trade tensions, is likely to limit the scope of further EU action.

These headwinds could see current resilience giving way to rising vulnerabilities.

Standard Chartered’s report, “Global trade – Surprisingly resilient, increasingly fragmented” provides an overview of global trade in recent years and its outlook for the foreseeable future.

All data in this article comes from Standard Chartered and their research.

Limited evidence of “deglobalisation” to this point

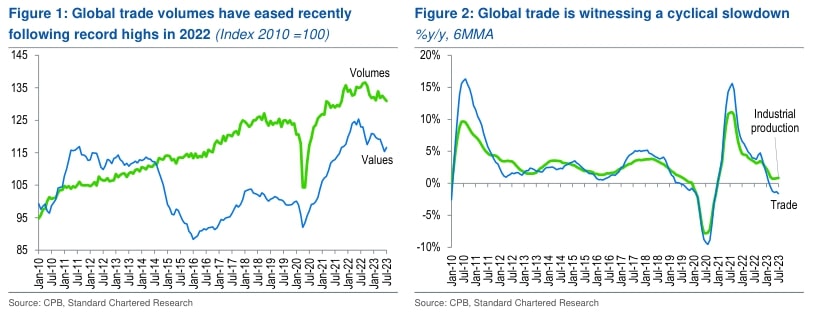

Despite the growing rhetoric and sentiment regarding the prevalence of deglobalisation and anti-trade positioning, global trade has shown resilience, reaching record levels of $32 trillion in 2022.

The report notes subsequent weakening on a cyclical basis but prioritised structural drivers that support a positive outlook for trade in its analysis. These positive elements include growing South-South, i.e., intra-EM, as well as digital services trade, which will drive global trade activity going forward. These trends are nevertheless likely to face counteracting forces from increasing geopolitical tensions.

South-South and digital services trade drive global activity

Global trade has remained resilient in the face of widespread deglobalisation coverage, as well as the stresses experienced by supply chains as a result of trade wars, geopolitical obstruction, as well as the pandemic.

Following former president Trump’s imposition of tariffs targeting China in 2017, global trade activity persisted, reaching new highs in terms of value and volume traded. Global value chain participation data has reflected mostly stable rates between 2007 and 2022, supporting the case that supply chain fragmentation is not as acute as originally posed by the “unwinding” narrative.

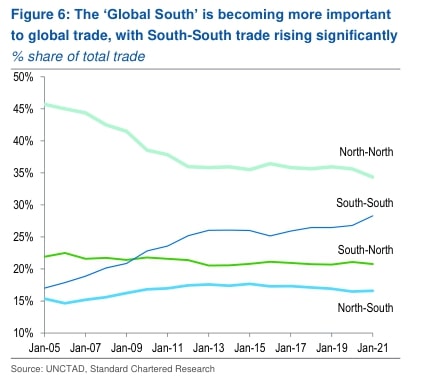

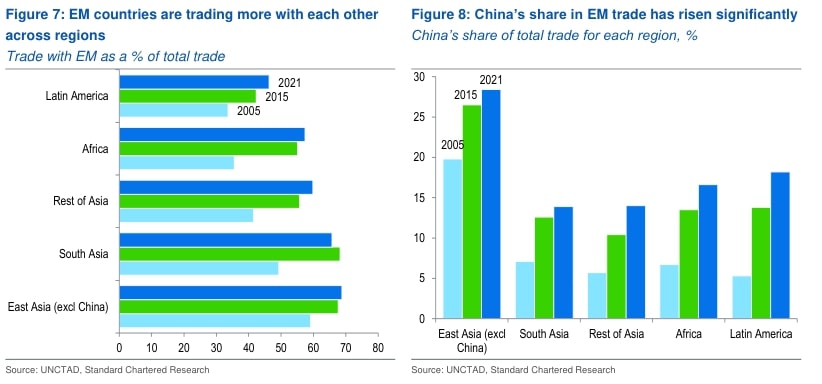

Driving this positive direction of global trade is increasing South-South trade activity, which has risen to approximately 28% of total trade in 2021, up from 17% in 2005.

This has had a divergent effect on North-North, as well as North-South trade. South-South trade activity now also serves as the most substantial portion of EM economies’ trade, particularly in Asia.

This is mostly China-driven trade, as other major economies in the region integrate with the Chinese economy, accounting for 20% of trade flows across all regions.

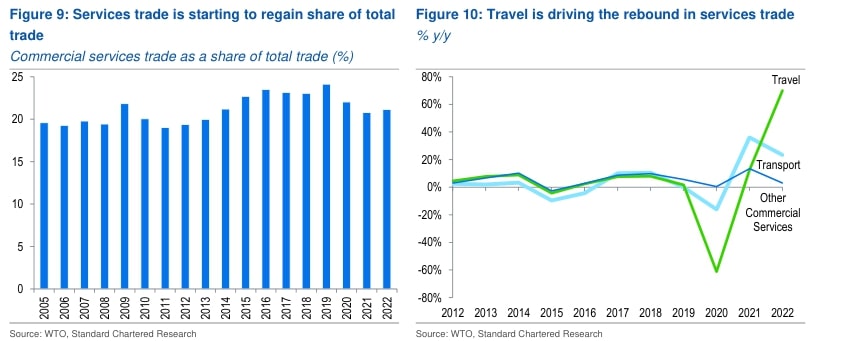

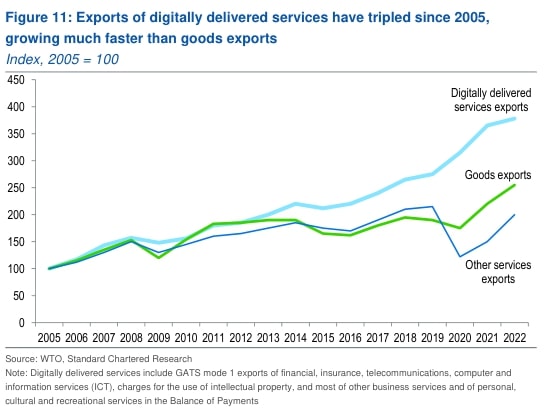

Trade in services is also in the process of rebounding, driven chiefly by a strong post-pandemic increase in travel activity. In addition to this, the increasing trend of digitalisation of economies has seen digital services exports increase to 12% of total trade in 2021, up from 4% in 2010.

This is a result of decreasing digital costs, as well as rapid digitalisation uptake, which will likely provide further support for growth in the sector over the coming quarters.

Geopolitics presents a significant risk to trade

However, geopolitical tensions are becoming increasingly restrictive for trade activity. The report notes that the resilience shown by global trade is likely to be weakened by ongoing geopolitical risks moving forward.

The key factor in this regard is the increasingly hawkish positioning of both the US and EU towards China. Whilst their approaches differ somewhat, the net effect is likely to be trade diverting, if not necessarily trade restricting.

Additionally, the US has continued to block the appointment of new judges to the WTO Appellate Body.

This has diminished the impact of the organisation, as trade is increasingly coordinated through bilateral or regional alternatives, thereby reinforcing the trend towards fragmented trade activity into regional corridors and agreements with limited global consensus.

Outside of the WTO, the US has sought to combat what it perceives as a strategic threat from China by deploying a range of tariffs, quotas, and export bans on strategic equipment such as high-end microchips and associated upstream industries.

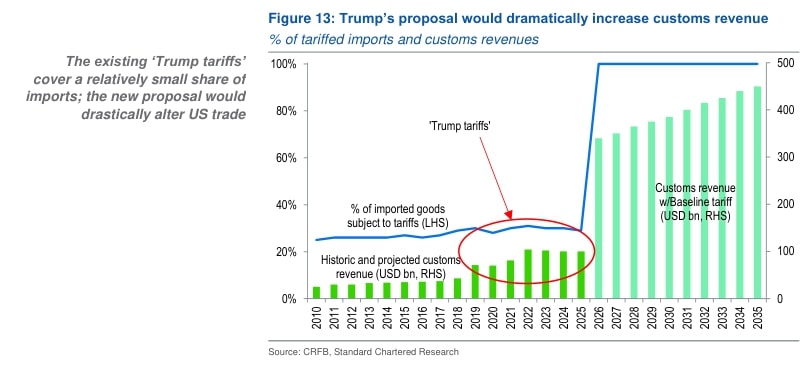

Whilst the Biden administration has shown no desire to return to trade liberalisation negotiations, it has not significantly escalated the Trump era actions. A Trump victory in 2024 could therefore present even further trade disruptions, with Trump already signalling the intention to increase import tariffs across the board.

Furthermore, both Republicans and Democrats agree on the threat posed by China and the need to contain it, particularly in the trade and national security spheres which could signal increasing trade tensions in the buildup to the election.

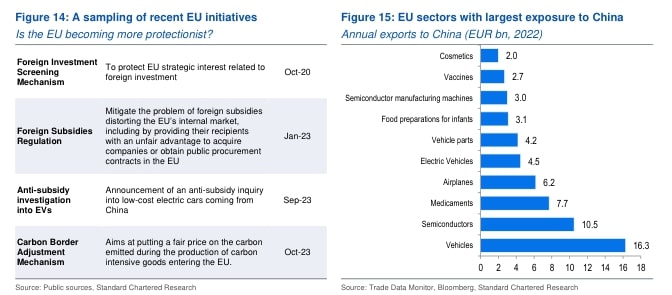

The EU shares concerns about China but is less able to act as decisively as the US. Nevertheless, it is headed broadly down the same pathway, albeit in a more gradual fashion. This raises the risk of tit-for-tat measures between the two.

US-China trade contracts, to the benefit of Mexico and Vietnam

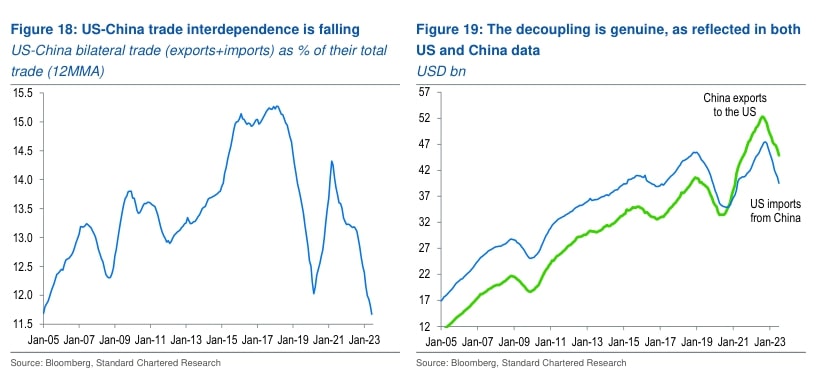

Despite the clear decoupling of US-China trade, global trade has shown resilience in the face of this trend. Trade interdependence between the two economies has fallen from a high of 15% of total trade pre-pandemic to approximately 12%.

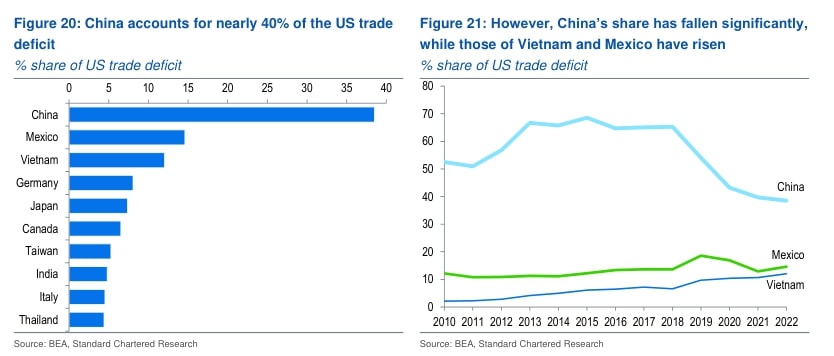

Further, whilst China remains the biggest element of the US trade deficit, its share has fallen from around 68.5% in 2015 to 38.5% in 2022. Canada, Mexico, and Vietnam have filled this gap.

The Vietnamese share of the US trade deficit has seen the largest increase, rising from 2% in 2010 to 12% in 2022. Nevertheless, the China factor still remains in this relationship, as this could in part be a reflection of Chinese exports to the US via factories and supply chains in Mexico and Vietnam.

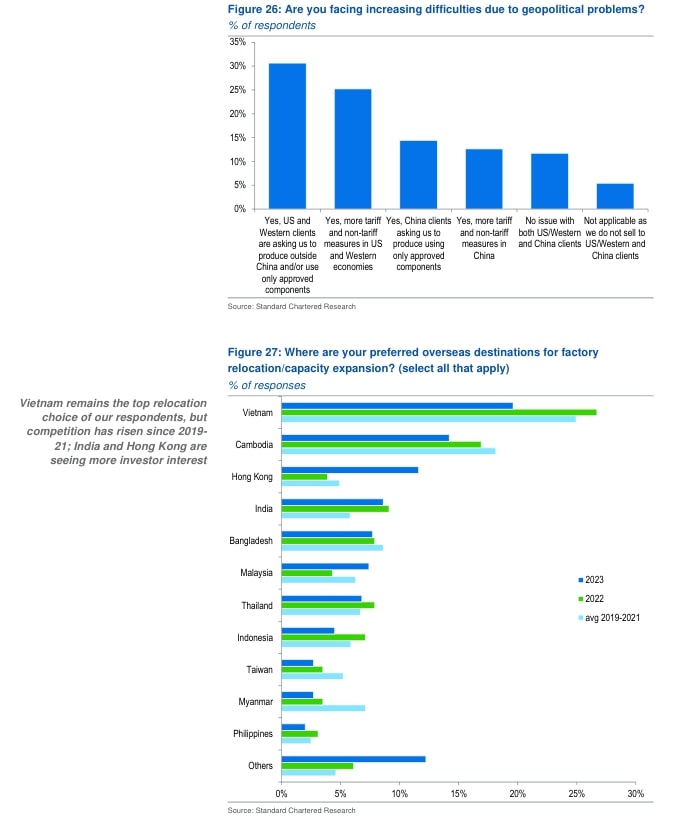

Geopolitical tensions are also stretching established supply chains. Whilst manufacturers continue to prefer China for their operations, geopolitical considerations are reportedly driving them to diversify locations.

Over time, this will continue to benefit countries like India, Mexico, and Vietnam, with ASEAN and South Asia more broadly best placed to take advantage of the opportunity presented by the bifurcation of supply chains.

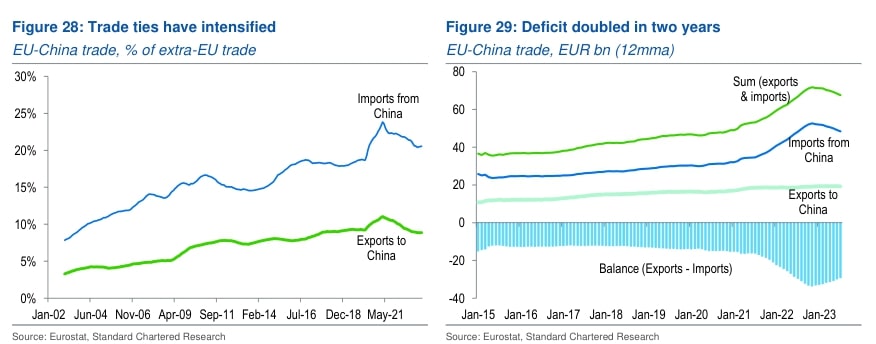

The EU’s de-risking efforts

China’s share of EU imports and exports has increased dramatically over the past two decades as economic ties have solidified in tandem with China’s rise.

However, this trend is now slowing, and may in time reverse, as the EU seeks to reduce dependence on imports of critical raw materials from China.

Another potentially more damaging dimension here is the dependence of EU companies on China as an export market, which the EU is increasingly attempting to limit. These two trends will likely reduce EU-China trade volumes in a slow but steady fashion.

The initiation of an anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese electric vehicles, which is likely to become the largest in EU history, presents a new threat to EU-China relations and reflects the EU’s increasingly firm stance on trade.

The EU has signalled intentions to conduct additional investigations in other industries but may be dissuaded by the high economic and political costs of escalated trade tensions and diverted activity from China.

Outlook: Green shoots in the face of systemic challenges

Global trade dynamics are experiencing a structural shift. Up to this point, the sector has weathered these challenges, but it is difficult to be sure how long this trend can continue.

A key consideration is US-China relations which are unlikely to cool and could in fact escalate depending on the outcome of critical US elections next year. The EU has, more cautiously, followed a similar approach to China as the US, which could further disrupt current trade patterns.

Growing South-South trade activity, as well as the expanding digital economy, may somewhat counterbalance negative trade trends moving forward.