The financial belt is tightening around China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Many headlines in recent weeks highlight the mounting debt and declining activity that the “project of the century” is now facing.

The total value of debt issued by Chinese financial institutions in BRI countries since 2020 that has needed to be renegotiated has now reached $52 billion.

In addition to this BRI project spending in several critical countries, like Russia and Sri Lanka, has dropped to zero.

This is a far cry from the $890 billion of investment and construction contracts that made it into the project between 2013 and 2021.

This stutter step in the BRI comes around the same time that the G7 unveiled its $600 billion Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) plan.

The PGII is a similar program to the BRI designed to help drive infrastructure investment in low-and-middle-income countries over the next five years,

Amid this shakeup, it pays to look back at some of the key benefits for China that comprised the original strategic rationale behind the new silk road.

Three strategic drivers of the Belt and Road Initiative

Three strategic drivers of the BRI for China are the creation of alternative shipping routes, the ability to shift manufacturing to the interior, and an increase in foreign demand for domestically produced goods.

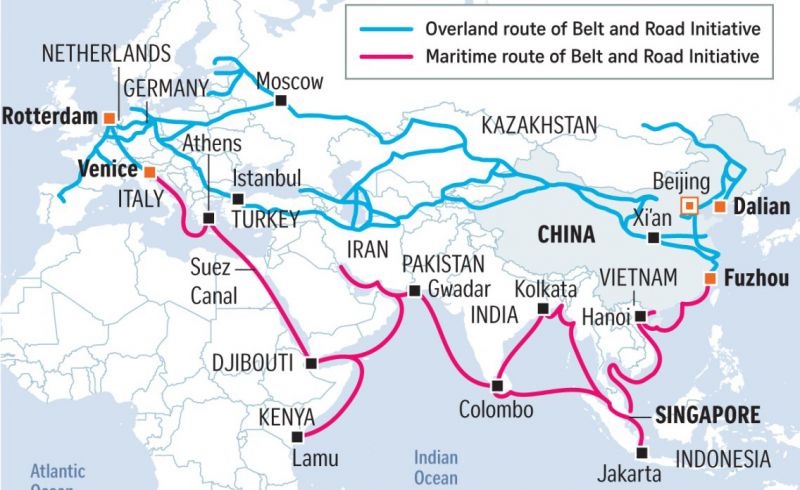

Create alternative shipping routes

Over 60% of China’s trade travels over water, with $874 billion passing through the South China Sea each year.

By sea, the fastest route from China to Europe and the Middle East is through the Malacca Straights – a narrow water passage between Malaysia and the Indonesian Island of Sumatra.

Almost 80% of China’s oil and natural gas pass through the Malacca Straight, making this stretch of water critical for the Chinese economy.

Furthermore, ocean shipments from China to Europe must also pass through the Suez Canal.

As the world learned from the Evergiven debacle of March 2021, an overreliance on a single, narrow shipping lane can lead to substantial delays if something goes wrong.

One significant strategic benefit of the BRI – particularly the overland route – for China is that it opens up alternative land-based shipping corridors to the South China Sea, Malacca Strait, and the Suez Canal.

Shifting manufacturing to the interior

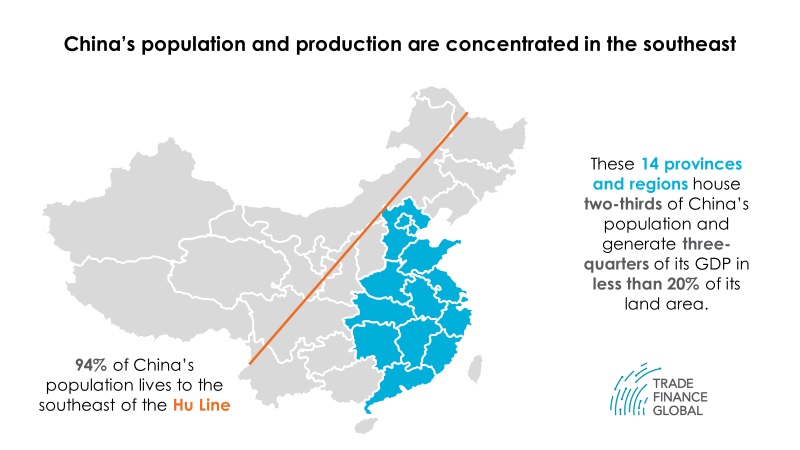

While China is still the largest country in the world by population and the world’s largest manufacturing centre, its population and production are not evenly distributed throughout the country.

Most of the country’s manufacturing is completed in three dominating coastal regions: the Dongbei Area in the northeast, the Yangzte River Delta Region around Shanghai, and the Pearl River Delta Region in Guangdong.

Furthermore, upwards of 94% of the total population live in 33% of China’s landmass to the southwest of the so-called “Hu Line” – which runs from the city of Heihe in the north to Tengchong in the south.

Much of this present-day population distribution stems from decades of migration to find work in China’s manufacturing regions.

Since most of the goods currently exported from China are sent by sea, factories are increasingly set up close to major coastal ports to reduce transportation costs to the ports.

Unfortunately for China, when you have the world’s largest population crammed into a third of your available land, things start to get a little crowded.

However, as the overland BRI routes begin to facilitate the flow of goods from China to Europe and everywhere in between, factories will be able to set up shop in other regions of the country without having to incur debilitatingly high shipping costs.

This will incentivise factories to move further inland, bringing economic activity to more remote regions and potentially helping to ease China’s population overcrowding issues.

Increase international demand for Chinese infrastructure supplies

As China rose to economic prominence in the last few decades, its manufacturing capabilities have naturally risen as well.

While this boost in economic output was great for a time, eventually it led to a situation where several key industries – such as steel, construction materials, electrical power infrastructure, and rail manufacturing – suffered from overproduction.

As it stood, demand in the global market simply was not able to keep up with rising Chinese supply, leading to price declines for these goods.

To maintain its thriving manufacturing sector, China needed a way to get people to buy its products.

By launching the belt and road initiative and investing heavily in foreign markets, the manufacturing giant was able to foment the very international demand that its domestic producers needed to continue turning a profit.

This is because Chinese lenders would offer funding to nations on the BRI route to invest into their own infrastructure.

In effect, this meant that Chinese financiers gained interest income, Chinese construction supply manufacturers could benefit from the higher prices that come with increased demand, and the host countries could enjoy enhanced infrastructure in their country and the prospect of future trade flows.

As the world continues to reel from the COVID-19 pandemic, the future state of the BRI may need to continue pivoting but the decision makers behind it should bear these founding principles in mind when forming decisions about its route forward.