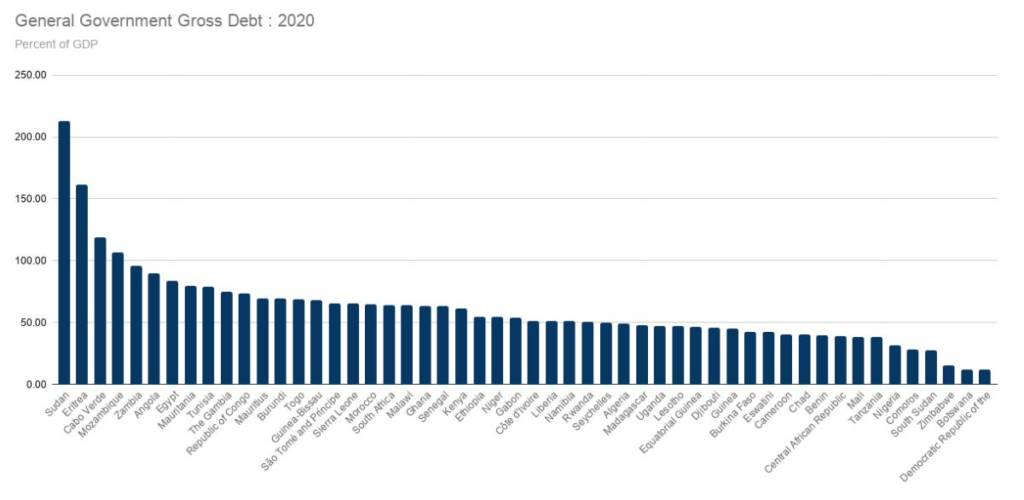

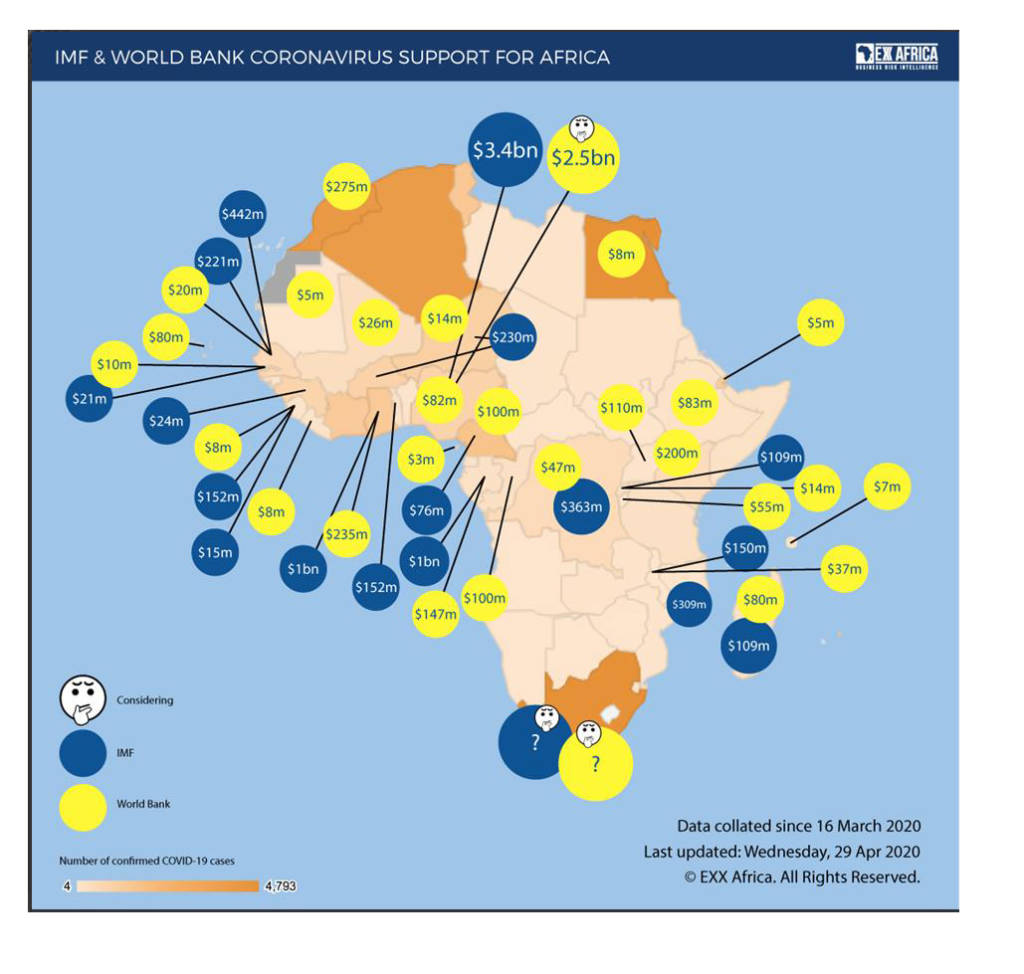

Africa represents one of the finals waves of the spread of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). The continent – which has a population of 1.2 billion people – has logged just 50,000 cases and less than 2,000 deaths to date. While the largest number of cases have been reported in northern and South Africa, the situation is changing quickly, as new hotspots are emerging in West Africa and even in the continent’s conflict zones (see figure 1). As COVID-19 gains momentum, we are already witnessing its impact on country risk as it threatens the economic, political and security health of the continent.

The economic impact

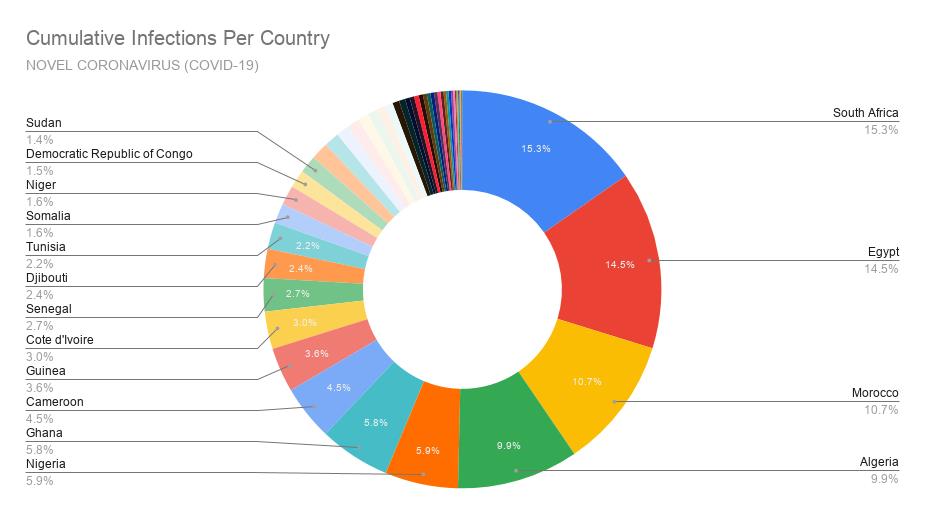

Beginning with the economic impact of the virus, it’s useful to recall the state of African economies before COVID-19 arrived. On the one hand, many economies were set to achieve high levels of growth this year with the continent as a whole expected to grow by 2.9 percent. On the other hand, there was an underlying concern of rising debt as a percentage of GDP across the continent (see figure 2).

Indeed, at the start of the year, several sovereigns remained at high risk of a major financing shock. Moody’s Investor Services noted in February, for example, that countries like the Republic of Congo, Mozambique and Zambia were the most exposed to credit risks. Other countries like Ghana, Angola and Kenya were deemed to be highly vulnerable.

As the first quarter passed, the continent was all of a sudden facing COVID-19 and a dramatic drop in the global oil price. The latter is important as some of Africa’s biggest economies are oil producers with high levels of debt.

Taken together, these two effects are now expected to wreak havoc on Africa’s outlook for the year.

In the World Bank’s latest biannual report that was released in April, it is now forecasted that Africa will tip into recession for the first time in 25 years this year. It forecasts that real GDP growth will reduce to around -2.1 percent with the potential for it to drop to -5.1 percent. This is a dramatic turnaround to the outlook provided just a few months ago.

With high levels of public debt and an historic recession on the cards, the main question is: How Africa is going to finance its response to COVID-19? Indicative of the mammoth financial layout ahead, the UN has estimated that Africa needs more than USD 200 billion to respond to the pandemic. To date, this gap has largely been filled by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (see figure 3).

Yet, while these institutions have helped to plug this gap, concerns around the continent’s debt remain, as bilateral lenders, such as the US, India and China have been slow to reach an agreement on debt relief or even debt restructuring.

As such, the continent’s financial ability to respond to the virus is in serious doubt. This, in turn, will contribute to higher economic risks this year, such as the risk of a sovereign default, but also higher political and security risks as well.

The political impact

2020 was always going to be a big election in year in Africa with at least 22 countries scheduled to hold elections. Whether these elections take place will depend on how long individual states take to contain COVID-19. While this is uncertain, what is clear is that in response to COVID-19, at least 40 governments in Africa have implemented movement restrictions and 26 have declared states of emergency or states of disaster. All of these measures are expected to impact elections.

In some instances, elections have proceeded, such as in Mali which held its first parliamentary elections since 2013 in March. Unsurprisingly, voter turnout was at a record low with a turnout of just 12.9 percent in the capital. Another country that pushed through elections is Guinea, which went to the polls in late March to elect members of parliament and vote on a proposed constitutional reform. These elections were held against a backdrop of street protests and despite the threat of COVID-19. A similar unwarranted pushing through of elections is expected in Burundi in May.

Other states have sought to delay elections amidst the virus. Ethiopia, for example, has postponed its much-anticipated vote scheduled for August. While this has been welcomed by the opposition, in other locations, heads of state may choose to delay votes to their advantage. This is expected in Malawi, which is scheduled to hold a rerun of its elections in July. Yet, because the incumbent is expected to be unseated, he is likely to postpone the vote. Somalia’s elections are also likely to be postponed this year, much to the ire of local leaders.

In each of these cases, the holding or delaying of elections during COVID-19 ultimately undermines the credibility of many African governments, contributing to another set of country risks, including the risk of civil unrest and political violence.

PODCAST: All Change in Africa: EXX Africa’s Dr Robert Besseling on the Business Sentiment in Africa (S1E9)

The security impact

Beyond the economic and political impact of COVID-19, the novel coronavirus has the potential to exacerbate conflict in Africa. Non-state actors, such as Islamist militant groups and insurgent groups, have already demonstrated the intent and capability to exploit the pandemic to their advantage.

Unprecedented attacks have been reported in Mozambique and the Sahel since late March, for example, as Al Qaeda and Islamic State-affiliated groups have sought to expand their operational footprint and boost their supplies whilst attention is turned elsewhere. In Libya, Khalifa Haftar’s offensive against Tripoli has raged on. Despite calls for a ceasefire to allow healthcare workers to respond to the pandemic, heavy shelling in Tripoli has been reported, as Haftar has sought to gain more ground to use as leverage during impending negotiations.

At the same time, COVID-19 has hindered the ability of those stakeholders mandated to oversee peace agreements and combat these non-state actors.

The AU’s Peace and Security Council decided to suspend its work until at least mid-April, for example, yet key issues on its agenda included major mediation initiatives, such as the peace agreement in South Sudan. The deployment of security forces to conflict zones has also been affected, as all rotations and new deployments to the AU Mission in Somalia were temporarily suspended. A similar halt on rotations occurred in the Sahel.

Without forward movement on these agreements and the maintenance of forces on the ground, COVID-19 therefore also runs the risk of creating a major security vacuum in Africa which non-state actors are sure to exploit, raising the risks of war and terrorism this year.

The most vulnerable countries

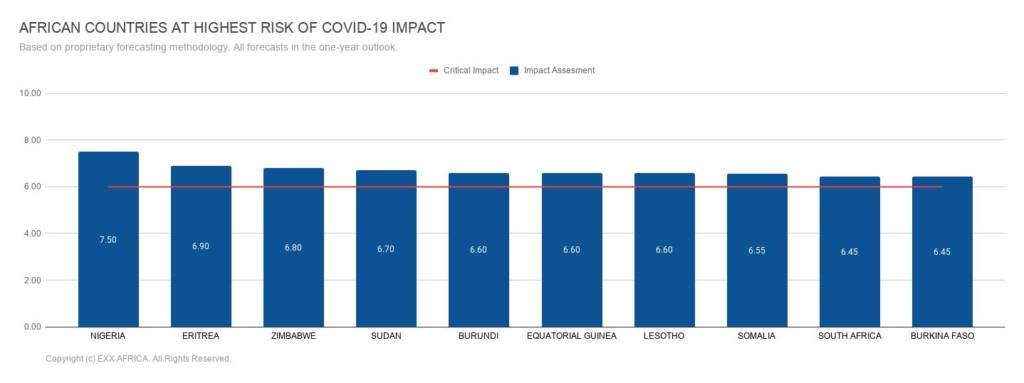

Taking all of these economic, political and security factors into account, we at EXX Africa believe that the following countries are the most vulnerable to a country risk drop as a result of COVID-19 this year.

The above ten countries clearly demonstrate the key risks discussed. For example, many of these countries have high levels of debt (Sudan, Eritrea, Burundi, South Africa), are oil economies (Nigeria, Equatorial Guinea, and Sudan), are in an election year/are facing political pressures at home (Burundi, Lesotho, Somalia, Burkina Faso), and/or are facing a local insurgency or a militant threat (Nigeria, Sudan, Somalia, and Burkina Faso).

EXX Africa provides open access reporting on COVID-19 in Africa. Please visit our website for further information.