Blockchain is not just the latest gimmick in trade finance, it’s a necessity for speeding up and expanding future credit to those trading businesses who will need it more than ever, post-Covid. However, if regulators and established financial institutions are to place their faith – and their capital – in its continued development, it must have a financial crime control framework to match the dynamism and efficiency of the solutions it offers.

What is blockchain in a trade finance context?

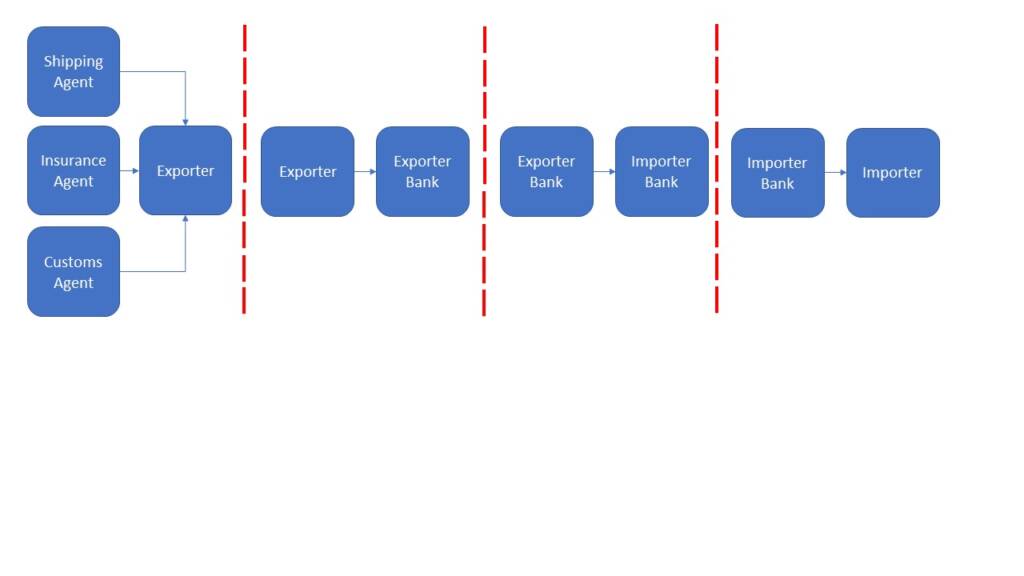

More accurately termed as distributed ledger technology, blockchain allows all permitted participants in a trade finance deal to maintain a live copy of, or access to, the transaction ledger for full and up-to-date visibility. At its most basic level, think of the importer, exporter, and their respective bankers logging in to check what stage it’s at and trigger their financing. Once you add to that the insurers, shipping agents, and perhaps even customs authorities, and you can start to imagine the scale and speed of information availability that this technology could bring. It supports faster, cheaper transactions, and may represent a huge leap forward in automated or even straight-through processing in a world more used to waiting around for a SWIFT message or a couriered paper packet to arrive at a bank’s counters.

What are the building blocks in the blockchain?

To keep their in-house ledgers up-to-date, trade finance providers graduated over the years from communicating with one another via paper mail, fax, tested telex messages, to today’s more ubiquitous SWIFT network. In their own ways, all of these methods rely on reference numbers and pre-agreed codes and passwords to allow the participants to have faith in each other’s messages – a gradual move to the public key cryptography standards we rely upon today. Arguably, all these methods continue to rely upon a one-to-one communication exchange, creating information siloes, blockers and transaction delays.

Blockchain platforms upend this, by distributing the ledger into numerous, simultaneous copies – for live visibility by all enabled participants. Instead of an exporter’s document presentation to their banker being known only to those two parties (and reflected in their private ledgers), now all other participants can also see their live ledger copy, and can start their new deal stage administration or financing without undue delay.

What do financial crime controls have to do with it?

The trade in goods and services, financed or not, has long been used as a facilitator for organised crime to clean and even grow their cash reserves. In a 2016 report, the OECD quoted UN estimates of well over $400bn in criminal profits being laundered through the global financial system, or 0.75% of global GDP (OECD, 2016). Rightly so then that the payment and financing networks that support global trade are tightly regulated.

A typical trade finance bank has a plethora of financial crime controls in operation:

- Manual Anti-Money Laundering (AML) transaction monitoring by trade finance staff

- Looking for the less binary risk indicators or ‘red flags’ that a trained eye, common sense and gut feel can uncover

- Seeking document inconsistencies (6 crates on a Bill of Lading, but 6 kilos on an invoice?), trade flows that make no sense (shipment of coffee from the UK to Brazil?), and other more complex typologies

- Automated AML transaction monitoring, often applied to trade finance and open account payments alike

- Comparing transactional activity to Customer Due Diligence records

- Performing pattern recognition, seeking anomalies compared to transaction history, in volumes, value, counterparty jurisdictions and more

- Searching for known typology parameters and risk indicator combinations

- Over time, the manual monitoring efforts of trade staff (above) are absorbed into automation, as optical character recognition (OCR) and robotic process automation (RPA) are used to scan and transpose paper documents digitally, and complex typologies are better coded into automated monitoring algorithms, and machine learning added to improve their parametrization

- Fraud risk monitoring

- Overlaid or in parallel with AML monitoring, with automated fraud risk scenarios, plus manually sought risk indicators

- Real-time sanctions screening

- Self-explanatory, and often extending in scope in trade finance to sanctioned transit risk, where shipping documents coupled with geographic knowledge may simply suggest that goods risk passing physically through sanctioned territories to reach their ultimate destination, and so require further investigation

Distribute the FinCrime controls alongside the ledger?

Back to blockchain, and if this technology offers more efficient processing, surely distribution of the financial crime controls listed above among all participants is equally efficient – in a ‘divide and conquer’ approach? Unfortunately, reality is never so simple. No regulated institution can absolve itself of its high-risk control responsibilities by laissez-faire outsourcing, in this case via uncontracted reliance upon its deal counterparties or blockchain platform provider.

Outsourcing is of course achievable under existing controlled mechanisms: Through formal third-party contractual and service level agreements, and ongoing vendor management and assurance oversight. This, however, is unlikely to be a desired option specifically for AML, fraud or sanctions controls between trade deal counterparties.

The blockchain platform provider is a more interesting option. At its core, the provider is a technology company, providing cryptography upon which its users can rely for their secure communications. It designs an architecture of nodes (blockchain user computers which will each maintain copies of the ledger), probably also a user-friendly interface (a website for manual login), and perhaps even a design for automated data transfer feeds to and from the node and the trade counterparties’ internal ERP or accounting platforms (via API or any other nimble, cost-effective connectivity solution). Its expertise begins to stretch when it is also sets the legal framework in which trade counterparties must operate. Some of the more challenging questions it may have to answer already include:

- Within its ecosystem, does it mandate adherence to established industry norms, such as the ICC’s UCP rules? Contour is an example provider to have chosen this route. Or does it set its own rules through contractual agreement?

- Does it establish new product or service definitions? We.Trade is one example, with its introduction of ‘Bank Payment Undertakings’ (BPU) described as a new ‘digital letter of credit’ (We.Trade Innovation DAC, 2020)

- Does the platform warranty the accuracy and completeness of the data, or merely the transmission of what it is provided through the node? What reliance can counterparties therefore place upon it?

- What avenues exist to seek restitution in the case of contractual dispute, particularly with no existing case law? Does the provider attempt to establish a governing board?

- What jurisdiction and competent legal authority apply, when the blockchain platform provider, and its multiple counterparty nodes all reside in scattered countries?

If this list were to be added to further, where the blockchain provider seeks to enter the ground of ‘RegTech’ and offer bolt-on services of AML transaction monitoring and sanctions screening (whether directly or by sub-contract to another third-party in turn), a multitude of regulatory requirements must be added to its skillset, and the prospect again appears unlikely to bear fruit.

Illicit activity blocked by the blockchain

In light of the challenges above, the potential for operational improvements in financial crime controls within a distributed ledger environment likely revolves around increasing their effectiveness, rather than efficiency. In place of outsourcing, think instead of a ‘many-eyed check’ and of intelligence sharing between subsets of counterparties.

This is by no means easy. Challenges to be addressed include:

- Cross-jurisdiction information sharing rules

- Managing the risk of Tipping Off under money laundering laws and regulations

- The supremacy of local sanctions laws over contractual payment obligations arising through the blockchain – albeit a common challenge with more traditional trade finance mechanisms

- The potential for commercial damages claims, where information sharing of an unsubstantiated suspicion prevents a counterparty from transacting its day-to-day business with the other counterparties. Case law provides a level of comfort in relation to Suspicious Activity Reporting (SAR) cases such as in HSBC vs. Shah (Coyle, 2012), but less clearly so under commercial contract alone

Where a blockchain platform provider is able to address some or all of these challenges up-front, the rewards are obvious. Blocking the spread of illicit activity is an ethical imperative and benefits society as a whole. Meanwhile self-interest is always self-evident, in this case preventing one or more counterparties from illicit activity protects all the others involved in the transaction – from unwitting facilitation of a crime such as money laundering or sanctions evasion, or by becoming victims of fraud themselves.

PODCAST: Wolfsberg Group: Fighting financial crime when the going gets tough (S1 E37)

Final link in the chain

Upon receipt of such intelligence from a fellow counterparty, normal operating rules apply:

- To review intelligence promptly on its merits

- To raise a SAR where appropriate, even if the other counterparty may have done so already

- To enact appropriate controls such as high-risk CDD renewal, sanctions exposure reviews, and transaction monitoring watchlist additions

If such instances of information sharing via distributed ledger ecosystems are a parallel to the universal benefit of strong bonds with our trading partners, then the direction is clear. Let’s keep building those blocks and strengthening those chains, and we’ll see trade finance growing alongside.