In light of Canada’s Prime Minister Trudeau resigning as his party’s leader in early January, and with Mexico’s President Sheinbaum only holding office since October, Donald Trump may be facing an entirely new set of neighbours upon taking office at the end of the Month.

As he prepares for a potential second term, the big question is: what’s next for Mexico? Could a new wave of tariffs or stricter rules under the USMCA push Mexico to the brink again, or has it learned enough from the past to weather whatever might come? Before diving into the future, let’s take a step back and explore how Mexican trade has evolved in the 21st century and what lessons it has learned from navigating its relationship with its powerful northern neighbour.

A brief look back at Mexican trade this century

When Trump entered the White House for the first time in 2017, the secure trading dependence Mexico had relied on for years felt fragile. Tariffs, trade wars, and a complete renegotiation of NAFTA threw Mexican industries into turmoil.

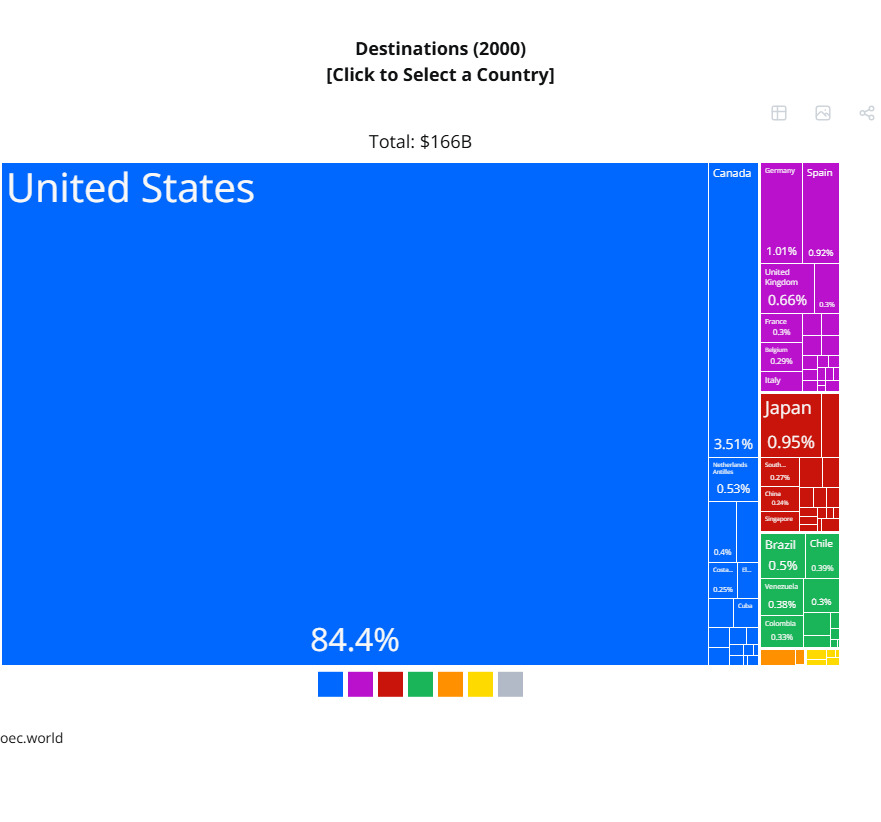

For decades, Mexico’s proximity to the United States shaped its trade policies, partnerships, and ambitions. Over 80% of its exports flowed north, creating a dependency that felt secure—until it wasn’t.

Mexico exports value by destination in 2000. Source: OEC

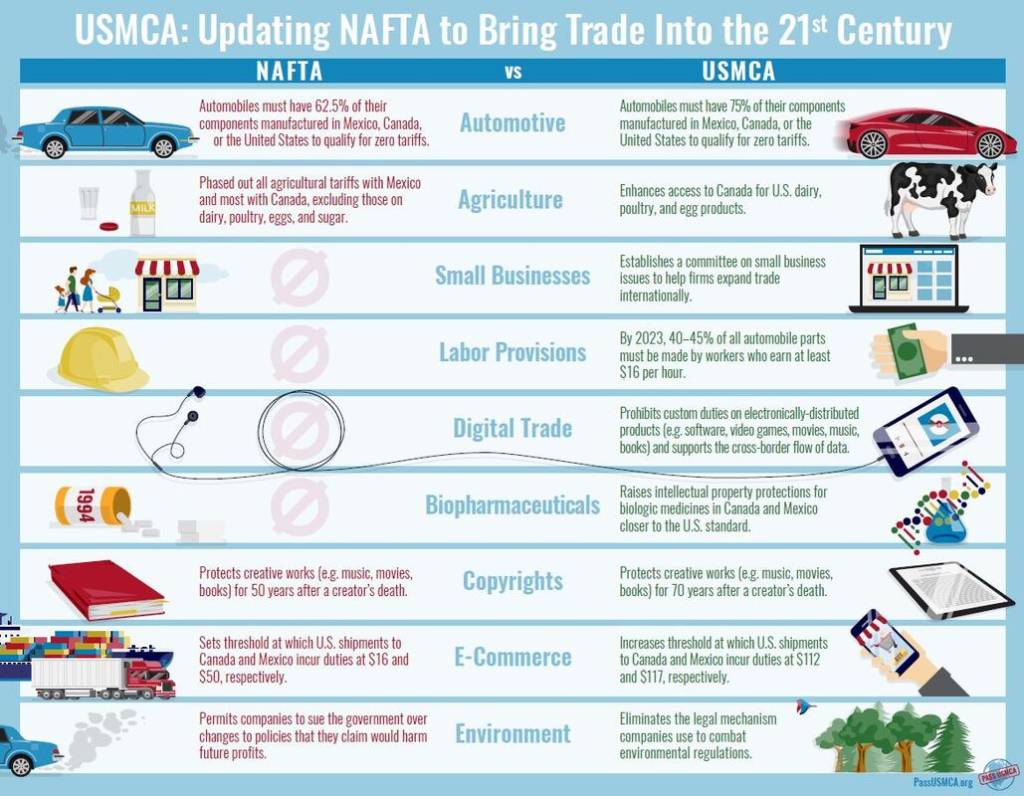

Trump’s first term in office brought a storm of change for Mexico. Renegotiations of NAFTA and the subsequent implementation of the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) shook the bedrock of Mexico’s economic reliance on its neighbour. Tariffs on steel, aluminium, and other key sectors further disrupted the balance. The uncertainty surrounding trade agreements and protectionist policies forced Mexico to confront its vulnerabilities.

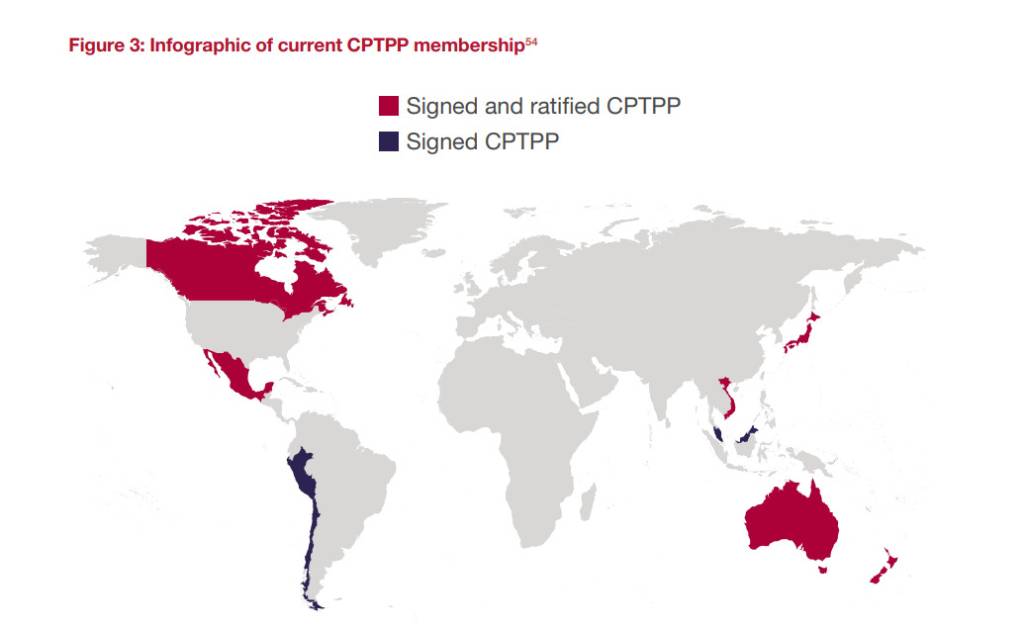

In response, Mexico turned outward, exploring partnerships beyond its long-standing dependency on the US. The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a trade agreement between 12 countries in the Indo-Pacific region, became a cornerstone of this strategy. Mexico’s inclusion in this multilateral pact opened doors to fast-growing markets across Asia-Pacific, including Japan, Vietnam, and Australia. These new opportunities allowed Mexico to expand its export portfolio, particularly in agriculture and manufacturing.

The country’s evolving relationship with China presented a more complex challenge. China’s influence grew as Mexico imported intermediate goods for its manufacturing sector. Simultaneously, Mexican exports like mining and agricultural goods found new homes in Chinese markets. Yet this relationship was not without its tensions. Competition between Chinese and Mexican goods in North America created friction, particularly as Mexico sought to maintain its foothold in the US.

Infographic of current CPTPP membership. Source: WEF

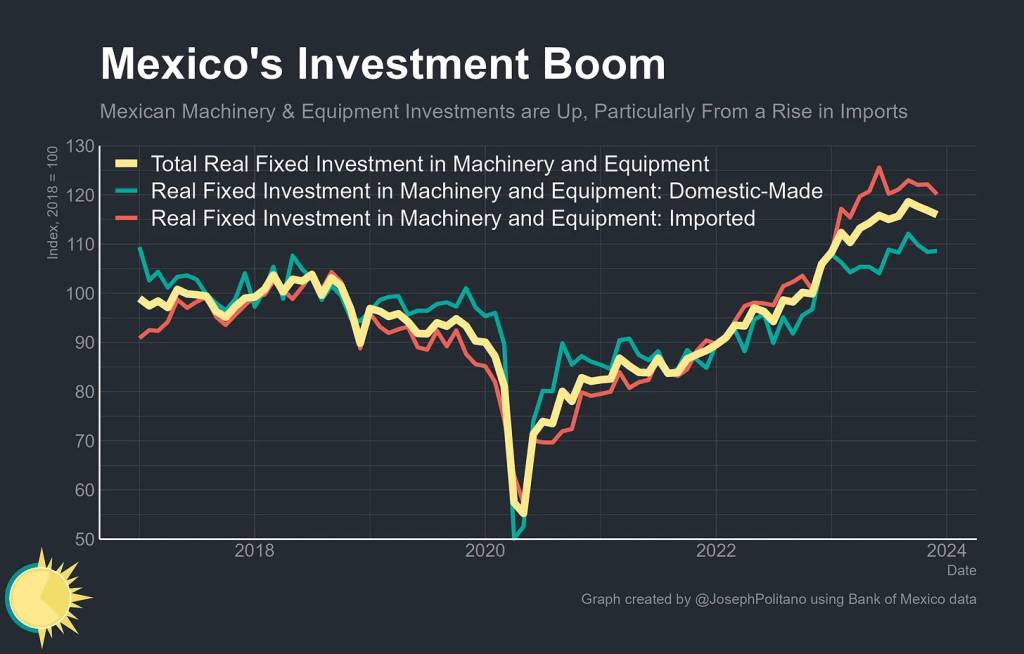

As global supply chains shifted in the aftermath of Trump’s trade policies and, later, the COVID-19 pandemic, Mexico found itself uniquely positioned to benefit from nearshoring trends. American companies, wary of overreliance on distant suppliers, looked to relocate production closer to home. Mexico’s geographic proximity, skilled labour force, and trade agreements made it an attractive alternative. Industries like automotive and electronics surged, with factories and assembly lines humming with renewed activity.

Mexico’s investment boom. Source: Apricitas Economics

The renewed activity, however, is once again being threatened, at least rhetorically, in the lead-up to Donald Trump’s second term as president of the United States.

A second Trump term

Trump’s protectionist rhetoric is not new. Before he took office in 2017, his threats to impose 35% tariffs on Mexico were routinely analysed. He has long advocated for an American-first approach to trade policy, regardless of what his many vocal critics say, and used this during the renegotiations of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) – which he dubbed ‘the worst trade deal ever signed’ – and in launching a trade war with China.

A second Trump presidency seems poised to amplify the trade war with China, creating ripple effects that would deeply impact Mexico. The imposition of 60% tariffs on Chinese goods, as the president-elect has touted – would likely affect Mexican manufacturing, given its reliance on Chinese imports for key components in industries such as automotive and electronics.

Goods manufactured in Mexico using materials imported from China could be considered of Chinese origin when exported to the USA if the imported materials constitute a significant portion of the product’s value or are insufficiently transformed during production in Mexico. Under rules of origin, such as those outlined in trade agreements like the USMCA, a product must meet specific criteria regarding local content and substantial transformation to qualify as originating from Mexico.

For example, if a car assembled in Mexico uses materials produced in China, and those components account for a substantial portion of the vehicle’s overall value, the automobile might not meet the regional value content (RVC) threshold of 75% North American content stipulated under USMCA.

USMCA: Updating NAFTA to bring trade into the 21st century. Source: Pacific Northwest Economic Region (PNWER)

Additionally, the agreement requires that certain core parts, such as engines, transmissions, and suspensions, originate within North America. If these core parts come from outside the region (e.g., China) and the vehicle fails to undergo a sufficient transformation in Mexico, the car could be disqualified from being treated as Mexican-origin for preferential tariff purposes when exported to the US.

This assumes that the USMCA, which is scheduled for review in 2026, survives Trump’s second term. The president-elect has already threatened to impose tariffs of 25% on all goods coming from Canada and Mexico if the countries do not secure their borders to the flow of irregular migrants and illegal drugs – a scenario that some predict would shrink Canadian and US GDP by 2.6% and 1.6%, respectively.

Many experts and commenters believe that the current round of tariff threats are more like political bargaining chips than an indication of the actual future trade policy, believing that Trump is only using these threats to gain concessions in other areas.

—

Trump in July 2015 described the Mexican government as “forcing their most unwanted people into the United States. They are, in many cases, criminals, drug dealers, rapists, etc.” Beyond a controversial social and cultural rhetoric, the impact of such strong statements against Mexican imports and economic collaboration will only be realised in time.

Whether Mexico will survive Trump is one thing. But a more pertinent question might be, ‘will the US survive another wave of Trump’s trade policies?’.