As Iain Martin of the Times said, “To deny the downsides of Brexit on trade with the EU is to deny reality.”

The decision to secede from the world’s largest single market area was bound to have some short-term economic consequences, but the UK may be experiencing more than a short-term decline.

Given the close timeframes between the UK’s official exit from the union and the outset of the pandemic, it has been difficult to determine which negative economic indicators are attributable to the secession and which more closely stem from the global lockdowns.

As the impacts of the pandemic on economic activity are drawing to a close now, however, the UK seems to still be lagging behind many other OECD countries – a phenomenon that experts are increasing attributing to the Brexit fallout.

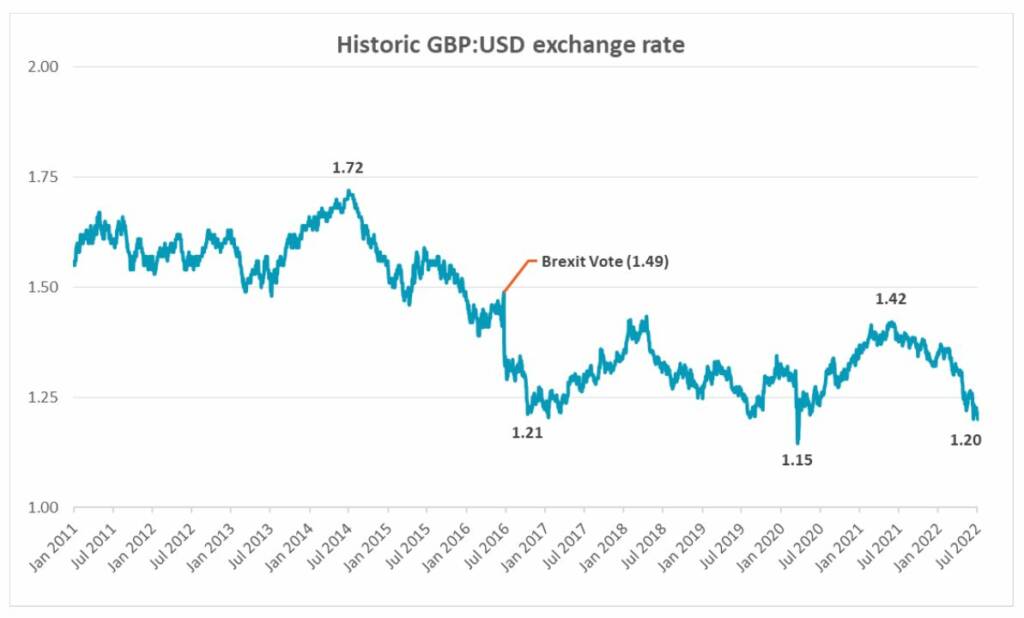

One such indicator that has been impacted is the value of Great Britain’s currency, the pound sterling.

UK currency devaluation

It took less than 18 months and one Brexit vote for the pound-dollar exchange rate to drop from its post-financial-crisis peak of 1.72 in July 2014 to 1.21, its lowest point since 1985.

The rate has never fully recovered and even managed to dip lower than this post-referendum trough following the double blow of the actual withdrawal from the union and the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020.

While currency values play a critical role in international trade, a nation’s imports and exports have a complicated relationship with its exchange rate because there is a continuous feedback loop between trade and currency values.

As a general rule, however, a weaker currency tends to boost exports while making imports more expensive.

According to the gross domestic product (GDP) formula, rising exports and shrinking imports lead to a larger net exports figure, which, ceteris paribus, directly raises GDP.

This vast simplification of macroeconomic reality, however, is not playing out for the UK in a post-Brexit world.

In March 2020, the Office for Budget Responsibility predicted that Brexit would reduce productivity and UK GDP by 4%.

The Office has not revised its projections over two years later, saying instead that it believes only slightly more than half of the damage has been realised to date.

To put the magnitude of this into context, a 4% decline in the UK’s $3.19 trillion GDP will result in $127 billion worth of lost output each year, which would cost the Treasury around $51 billion worth of lost revenues – this is equivalent to the UK’s total budgeted 2021/22 public sector expenditure on transportation.

This leads many to wonder what is actually happening with the UK’s international trade following Brexit.

Brexit impacts UK imports and exports

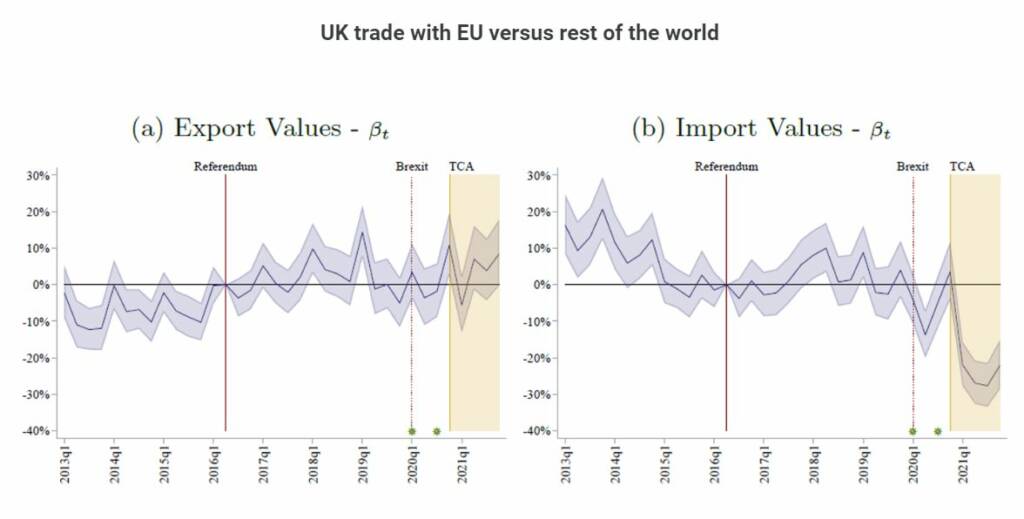

There have been many discussions surrounding the impact that the 31 January 2020 withdrawal would have on UK trading relations – especially those with the EU.

It was not until nearly a year later on 1 January 2021, when the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) – the free trade agreement governing trade between the two economies – came into force, that the UK’s trading relations with the EU were impacted by Brexit.

And impacted they were.

A study by the London School of Economics shows that while export values remained relatively stable, import values fell substantially after the implementation of the new agreement.

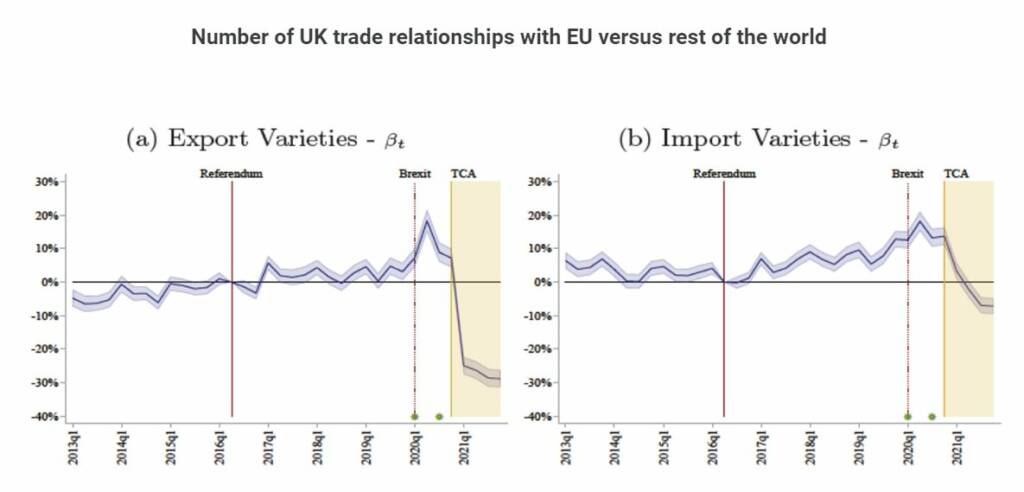

In addition to this, the study also shows that both import and export variety declined once the TCA come into force, suggesting a steep decline in the number of trading relationships in the UK.

The disparity between the value and variety figures also suggests that the increased costs of exporting caused by the TCA have forced many smaller firms out of foreign markets (decreasing variety), while larger firms have increased export volumes to help offset their fixed cost.

Increasing international trade costs are also impacting business investment in the UK and contributing to higher prices.

Declining business investment and rising domestic prices

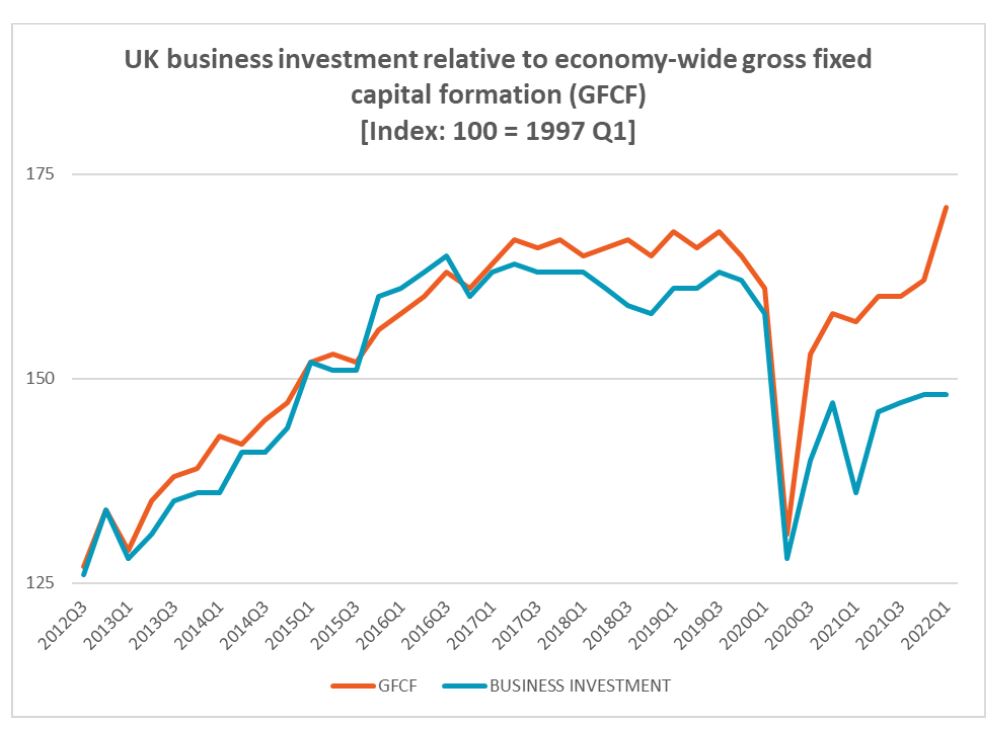

According to data from the Office of National Statistics (ONS), business investment fell 9.4% from 2016 to 2022.

While this decline can largely be attributed to the impact of the pandemic, there has been a clear flatlining of business investment since the June 2016 referendum.

Alongside other macroeconomic factors like the Russia-Ukraine conflict, this decline in investment coupled with increased barriers to trade is contributing to the record levels of inflation currently being experienced in the UK.

One example of this comes from the price of food.

In the report, The Economics of Brexit, the Centre for Economic Policy Research compared the price increase of imported food products that primarily came from the EU (like pork) with the price increase of imported food products that primarily came from other regions of the world (like pineapples).

The results show that food products coming from the EU have experienced a 6% increase in price relative to those coming from other regions.

For the average consumer, this can feel the same as a 6% “Brexit fee” added to their grocery bills.

This is especially troublesome given that the higher prices are not arriving with a corresponding wage bump for UK workers, decreasing purchasing power and increasing the costs associated with merely living.

In all, this data is causing many to question whether the decision to withdraw from the EU will ever be truly worth it.

Read the latest issue of Trade Finance Talks, July 2022