Covid-19 has certainly exposed the fragility of far-flung supply chains. What then will the future of global supply chains look like post-Covid? TFG heard from BofA on the possibility of SCF’s structural shift to localisation.

Featuring: Vikram Sahu (VS), Head of Asia Pacific Research, BofA Global Research

Peter Jameson (PJ), head of Asia Pacific Trade and Supply Chain Finance, Global Transaction Services, Bank of America

Host: Deepesh Patel (DP), Editor, Trade Finance Global

Vikram Sahu is head of Asia Pacific Research at BofA Global Research and has been with the firm since 2014.

Peter Jameson is head of Trade & Supply Chain Finance, Global Transaction Services (GTS), for Asia Pacific at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, based in Hong Kong.

The firm’s award-winning Global Research provides insightful, objective and in-depth research to individual investors and a wide variety of institutional money managers including hedge funds, mutual funds, pension funds and sovereign management funds to support them in making informed investment decisions.

China and its role in global supply chains

Deepesh Patel (DP): How important is China in terms of global supply chains, and what are the key trends over the last couple of decades? Why is China so important when it comes to manufacturing and global supply chains?

Vikram Sahu (VS): China is currently the largest exporter globally by a margin. In the past 40 years, it has risen rapidly from a largely agrarian society into the largest export hub globally, as it successfully reaped the benefits of globalization as well as demographic dividends in a Ricardian model of economic development to become the second-largest economy in the world. Especially, its accession into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2002 helped it amass a current account surplus with as many as 173 countries last year.

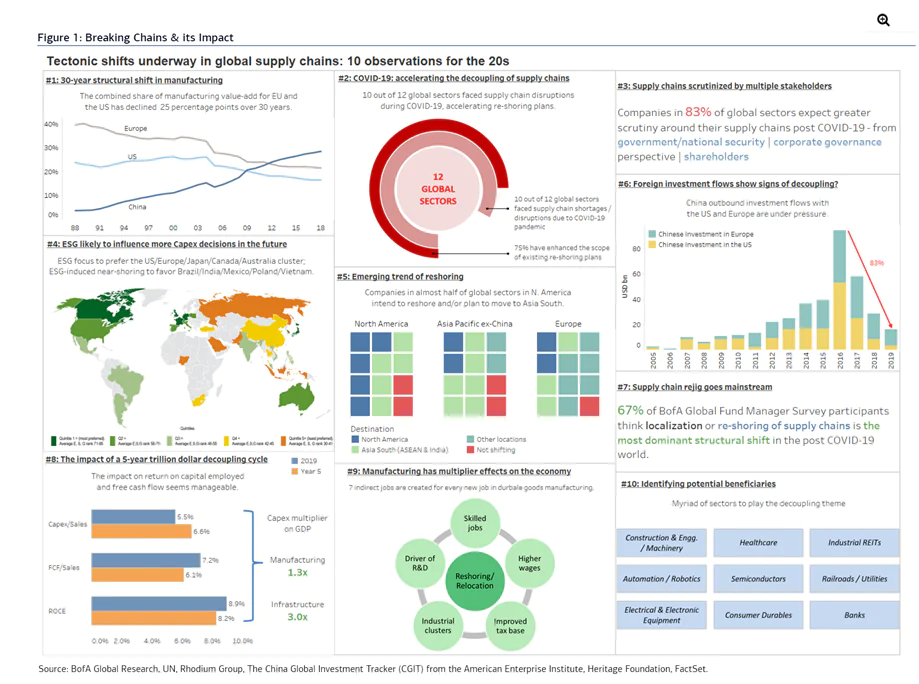

Global supply chains were established to maximize returns by optimizing labor cost arbitrage and lowering overheads. This led to a decline in the share of US and Europe in global manufacturing by about 25% points over the last 30 years in favor of low-cost countries, primarily China. What has made China the industrial heartland is that it offers the optimum mix of costs, quality, efficiency, human resources and infrastructure – precisely the qualities rewarded by globalization. The areas where it lacked somewhat, areas such as stricter environmental norms or regulatory frameworks, had taken a backseat in the past few decades. Unsurprisingly, it now accounts for a quarter of the world’s manufacturing value-added.

Re-shoring: An Overview

DP: What is re-shoring?

VS: To fully appreciate the meaning of this term, let’s take a step back.

In the old days, manufacturing took place in one of two places – either at the location of your primary raw materials, or in the vicinity of your distribution channels like rivers or ports. Ideally, both.

But, the advent of globalization post World War II turned it upside down. Globalization, as we know it in the modern economic sense, assumes, among other things, unfettered market access irrespective of the production location. As a result, global supply chains were established to maximize returns by optimizing labor cost arbitrage and lowering overheads, thereby allowing production to be location agnostic. Take a simple t-shirt that costs around USD10 for example. Its production takes at least two trans-Pacific trips plus three additional intra-Asia shipments for manufacturing and delivery. The full life cycle of the product could add another trans-Atlantic/Pacific shipment depending on how it is discarded.

Re-shoring, in essence, is a reversal of this process. It is a move back of production centers closer to the center of consumption, preferably within national borders and failing that, to countries that are deemed allies. There are myriad reasons for this, but the most important factor is an ongoing shift to ‘stakeholder capitalism’ whereby corporations focus on shareholders’ interests, as well as a broader community of consumers, employees and the state.

DP: Re-shoring is often a bit of a buzzword – we hear it often. Yet talking about re-shoring away from places like China, we are still confronted by the fact that China offers significant benefits (vs neighbouring other countries). What does your research suggest in terms of on the ground re-shoring – what is happening?

VS: It is not impossible, but not easy as well to move out of China. The industrial heartland of China has been touted as the “Goldilocks Zone” good reason because it has offered the optimum mix of costs, quality, efficiency, human resources and infrastructure for the past 30 years. No wonder, it accounts for a quarter of the world’s manufacturing value added. I read somewhere that the lead time to hit the shelves in US stores can take up to 40 days from Thailand, almost twice as long as from China.

Understandably, there are widespread concerns about the costs supply chain shifts away from China would incur. South East Asia and India are being touted as some of the alternatives, but there are concerns about capabilities. True, they have significant labor cost advantages, but capabilities are just as important. For example, it is estimated one Chinese worker can manufacture about the same value of goods as four workers from four ASEAN countries combined.

And yet, the relocations are coming through. There are a number of reasons behind this: rising wages, stricter environmental norms, a complex regulatory framework, the government focus to transform into a high-skill service-oriented economy, and, of course, the tariffs and the uncertainty around them.

To give you some recent concrete examples of on-shoring:

The newly announced TSMC fab facility in Arizona. TSMC intends to build and operate a fab in the US, with the support from the US federal and state government. The fab would utilize TSMC’s 5nm process technology with a capacity of 20,000 wafers per month. Construction is slated to start in 2021, with volume production targeted to begin in 2024. Our analysts estimate total capex would be around USD6bn. Assuming the company spreads out the capex spend over 2022-23, this project will account for more than 20% of the total capex expected during the two year period.

Another example is the upbeat response by corporates to India’s Make in India initiative: 22 firms including Samsung and Apple have applied to manufacture mobiles and another 40 firms have applied to manufacture electronic components within India. Based on the proposals submitted by these firms, they plan to manufacture USD153bn of mobiles cumulatively over the next five years, up 2.5x over the past five years. Over 60% of this manufacturing or an equivalent of USD93bn is aimed for exports over the next five years, a significant step up to USD4bn of exports achieved in FY20.

So, it is not just in the realm of rhetoric, it is happening for real.

Supply chains during Covid-19

DP: At the start of the year, BofA research suggested a reversal of supply chains moving from US/Europe to China – has COVID accelerated this?

VS: Absolutely, it has.

At the start of the year, we conducted a survey of our fundamental equity analysts who cover ~3,300 companies globally. As a reminder, this was eight months ago when most of us had never heard of COVID-19, unemployment was at historic lows and President Trump had just signed the Phase I deal with China. Against that backdrop, our survey findings were simple – global supply chains were on the move, although the depth of the shift was very limited. Interestingly enough, back in January only, we found that companies were planning to re-shore production. We argued that this was the first signs of reversal in a multi-decade trend during which manufacturing had shifted from the US and Europe to China.

Fast forward six months, and we find that COVID-19 has accelerated our calculus and exposed fault lines in global supply chains. A second survey of our fundamental equity analysts noted that, not just the healthcare sector, but companies in over 80% of global sectors experienced disruptions during the this pandemic. And, more importantly, as a consequence, over three quarters expect scrutiny of their existing chains and have widened the scope of their re-shoring plans.

It is worth mentioning here, that, this theme has now gone mainstream – 67% of the participants in our Global Fund Manager Survey, which covers about 200 investment managers running USD600bn, believe localization or re-shoring will be the most dominant structural shift in the post-pandemic world.

US/China trade war – A catalyst

DP: What’s the impact of the US/China trade war on re-shoring? Which industries will benefit from this decoupling?

VS: In a nutshell, it has acted as a catalyst.

Globalization first started pausing as early as 2008, and is now starting to reverse – both trade flows and capital flows have been on the decline for almost a decade now, Chinese investments into Europe and the US are down 83% since 2016. But President Trump’s policies have brought these into the spotlight.

Our first survey of our fundamental analysts back in January only found that global supply chains, worth roughly USD22tn market cap at the time, were on the move. Back then, national security concerns, and tariff walls – two key aspects of the US-China tensions – were cited as two of the key drivers.

Coming on the beneficiaries of this decoupling, technology is likely the biggest winner – robotics, cybersecurity, space research, AI, communications technology, vision devices, surveillance equipment, drones, semiconductor equipment, chip design, enhanced materials / alloys / rare earths etc. would benefit. Competition between the great powers will likely boost the defense industry as well.

As for the decoupling of supply chains, sectors that are involved in setting up new factories stand to gain a lot such as construction engineering, machinery, electrical and electronic equipment, factory automation and robotics, application software firms, etc. – basically all those who are essential for establishing new plants. Companies looking to relocate supply chains may choose to rent out industrial space for warehousing or storage purposes without building a new plant from scratch – industrial REITs stand to gain from such moves. Even auxiliary services such as utilities, railroads, banks etc. in the locations where supply chains finally end up are also potential beneficiaries.

Region or country-wise, the US is a clear winner. It has a massive edge in tacit knowledge and technology. As per our first survey in January, North America is also the preferred choice of destination for about half of all global sectors in North America that intend to move. The number, will most certainly, be higher only now. This is especially true for high-tech sectors and industries for which energy is a key input. Plus, it has under-appreciated ESG advantages – this is particularly important, as we believe that among the myriad reasons driving de-globalization, the most important is an ongoing shift to ‘stakeholder capitalism’ whereby corporations focus not just on shareholders’ interests, but also a broader community of consumers, employees and the state.

Many companies favor South East Asia and India also, especially for low end value chains, but emerging markets, in general, which have been the biggest beneficiaries of prior globalization – will likely be most challenged by its reversal. Emerging markets contiguous to the US or Europe like Mexico, Poland etc. may benefit, while the rest will need to rely more on domestic sectors.

The future of global supply chains

DP: What’s the future – are we likely to see a structural shift towards localisation?

VS: The short answer is yes. COVID-19 has exposed the fragility of far-flung supply chains that will move us from ‘just-in-time’ optimized inventory chains to ‘just-in-case’ excess inventory. Shifting the entire supply chain for a company is a structural shift with a long gestation period so it would be hard to put a timeline on it. But, I am reminded of famous German economist Rudi Dornbusch’s words in this context – “Things take longer to happen than you think they will, and then they happen faster than you thought they could” – it is likely that, now that the process has begun, it would get done faster than the consensus anticipates.

DP: From a financing and SCF perspective, what are the likely impacts this will have on (1) banks providing finance (2) corporates with SCF programmes?

Peter Jameson (PJ): It will be critical for corporates to brace themselves and their suppliers from the impact of these moves on their SCF programs, whether they are re-shoring or migrating supply chains to new markets.

Banks need to ensure they have a wide range of SCF capabilities so they can extend existing arrangements to the new markets where their corporate clients are moving to. They also play an important role in providing advisory and guiding their clients on any local market requirements or restrictions.

For corporates, it will be critical to partner with banks that have the flexibility to easily integrate new markets into existing SCF programs, as corporates expand into them. This will allow them to add new buyer/supplier entities and currencies as their needs evolve, in a way that minimizes incremental technology integration and avoids disruption to the available liquidity.