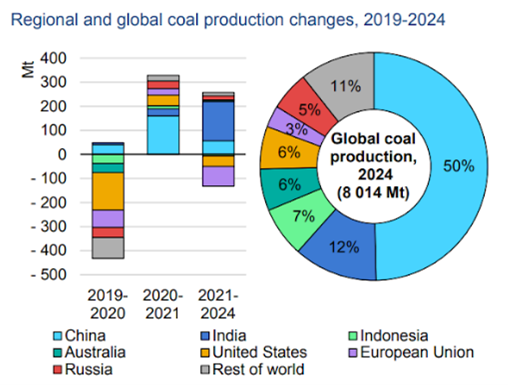

Global demand for coal, the least green of fossil fuels, is set to reach a record high in the next two years.

According to a report by the International Energy Agency (IEA), released at the end of 2021, global coal demand is forecast to reach 8 billion tonnes in 2022.

The decline in demand from high-income countries is expected to be offset by an increase in demand from emerging and developing economies.

Demand for coal in India, for example, is expected to grow 4% per year between 2022 and 2024 – an increase of 130 million tonnes.

Meanwhile, the growth of renewables in the US and the EU is likely to cut demand for coal in those markets even further.

Coal rebounded in 2021

According to the IEA report, a rise in fossil fuel demand following the reopening of the global economy has caused coal-powered electricity production to increase by 9%, while global demand for coal went up 6% in 2021. Thus reversing 2020’s decline in coal demand.

The global economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a 4% reduction in coal power for 2020.

A strong rebound in 2021 was driven by a combination of the global economy recovering faster than expected, adverse weather conditions boosting demand and reducing supplies, and all-time high gas prices.

The rebound in demand for electricity exceeded the growth in low-carbon supply. Consequently, many high-income countries relied heavily on fossil fuel power plants.

The IEA report estimated that India and China grew their coal-powered electricity generation by 12% and 9% respectively in 2021, reaching all-time highs in both countries.

In the US and the EU, coal power generation increased almost 20% in 2021, but was still short of 2019 levels.

China’s Influence

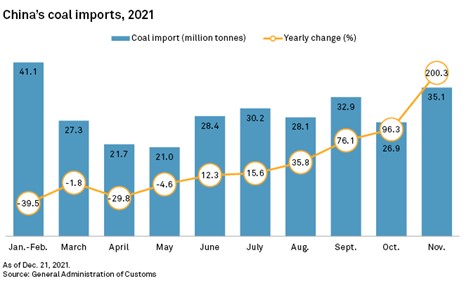

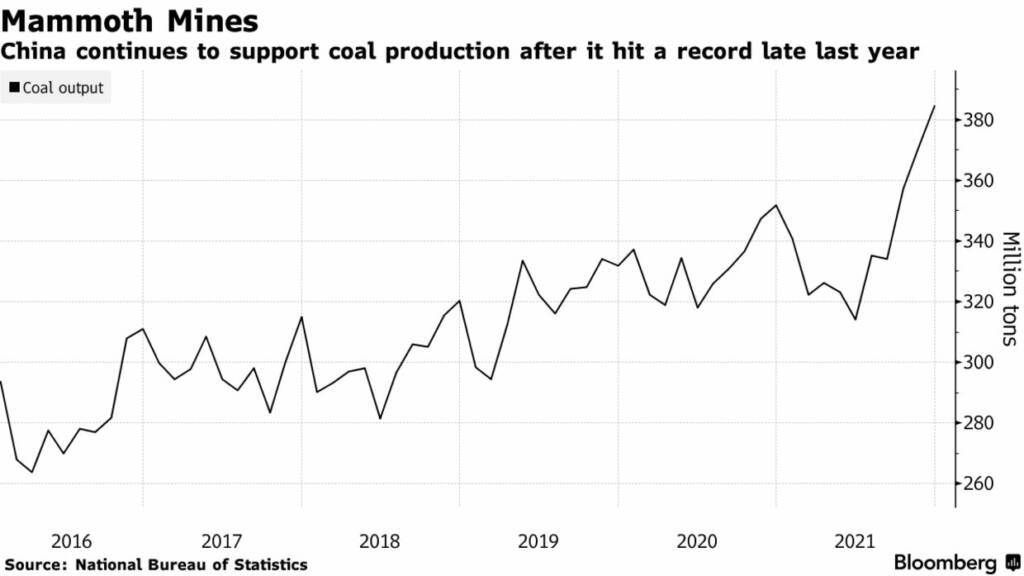

China’s power generation accounts for one third of global coal consumption. China is also the world’s largest producer and importer of coal, accounting for 23.4% of global coal imports in 2020.

This gives the country significant influence in global markets.

China’s national coal production reached an all-time high in 2021. At 4.07 billion tonnes, output had increased by 4.7% when compared to 2020.

China’s reliance on coal was stressed in the second half of 2021.

In September 2021, China imported 32.9m tonnes of coal, up 76% from the same period last year. This was the country’s fifth highest monthly reading for coal imports on record.

The surge in imports came as the government attempted to cope with the nationwide energy crisis brought on by fuel shortages.

Since mid-August, large scale power cuts affected more than 20 Chinese provinces, which gave the government no other option but to intervene to meet domestic electricity demand.

Industrial businesses were forced to ration power use, while mines were ordered to increase output significantly in order to safeguard supplies for an anticipated cold winter.

Record-high domestic coal prices, a rise in fossil fuel demand following the reopening of the economy after lockdown, and tougher environmental requirements all contributed to fuel shortages.

The increase in coal imports during September was an indication that authorities were looking for supplies elsewhere in a bid to lower domestic prices. Coal reached CN¥2,000 ($310) a tonne in the second half of the year.

After placing an embargo on Australian coal at the start of 2021, China has pivoted towards Russia and Indonesia to resolve its domestic shortages.

According to Chinese customs data, China imported 3.7 million tonnes of thermal coal from Russia in September 2021, more than 230% higher compared to the same period last year.

Meanwhile, China’s coal imports from Indonesia were up 89% from September 2020.

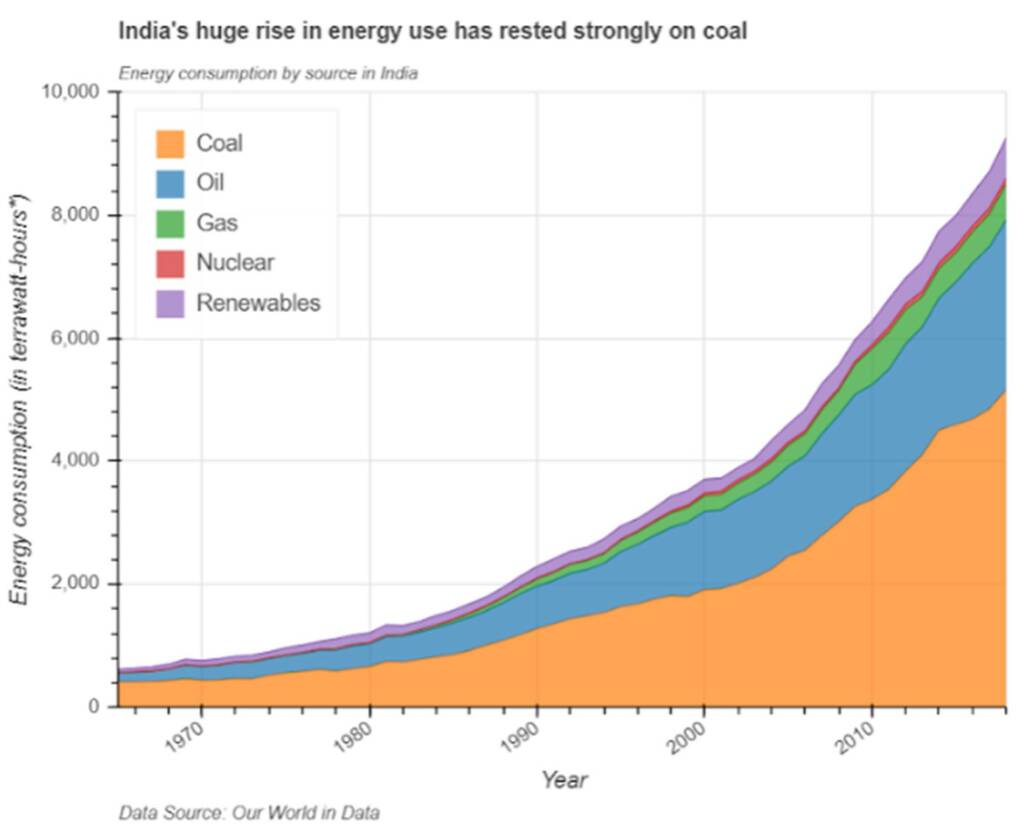

India unwilling to abandon coal

India is the second largest consumer of coal, but why?

Firstly, India has a population of 1.4 billion people, and therefore its demand for electricity is enormous.

About 70% of India’s electricity generation currently comes from coal, and coal producers in India are set to increase their production up until at least 2024, according to the IEA.

India’s domestic coal industry is one of the foundations of its economy, employing up to 4 million people directly and indirectly.

Coal also contributes massively to government revenues. In 2019, Coal India paid roughly 500 billion rupees ($6.7 billion) in taxes to federal, state, and local governments – which amounts to almost 3% of the federal government’s total annual revenue collection.

Following the energy crisis of 2021, India’s power producers are ramping up imports to rebuild their stockpiles.

NTPC, a state-run producer, imported 10 million tonnes of coal in October 2021, in its first international tender in two years.

In order to lift millions out of poverty, India’s energy needs will have to keep growing, as unmet demand could hinder economic growth.

What does this mean for climate agreements?

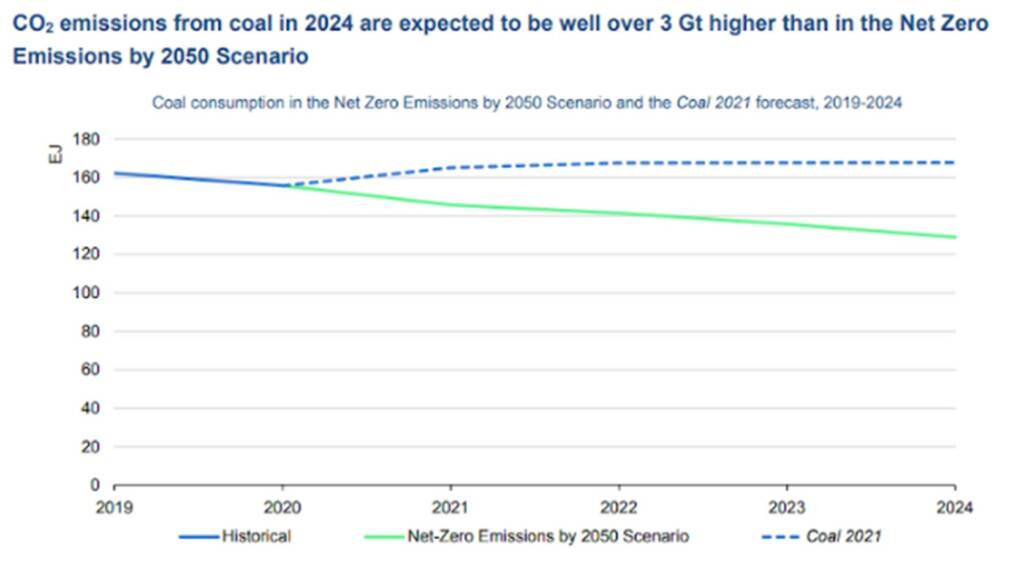

Rising coal consumption is threatening the trajectory of the global goals to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

At the current rate of consumption and production, the world will fall short of its coal-based CO2 emissions reduction targets.

Coal-generated electricity in 2030 needs to be reduced by 80% compared to 2010 levels if we are to limit global temperature rises to 1.5°C.

India and China both posted an all-time high for their 2021 coal-powered electricity generation.

And despite global efforts to combat climate change, China’s own climate pledges state that it will increase coal capacity year-on-year until 2025.

However, Chinese President Xi Jinping has also said that the country’s carbon emissions will begin to decline by 2030, and that the country will reach carbon neutrality by 2060.

After the COP26 climate conference in November 2021, China produced 384 million tonnes of coal in the following month of December, up 20% on the same period a year earlier.

Chinese policymakers have made it clear that economic growth remains their highest priority, and such growth is highly reliant on the state’s coal infrastructure.

At COP 26, India intervened with the pledge to abandon coal by changing the commitment from “phasing out” to “phasing down”.

This was to the dismay of Alok Sharma, president of COP 26: “We are on the way to consigning coal to history. This is an agreement we can build on,” said Sharma.

“But in the case of China and India, they will have to explain to climate-vulnerable countries why they did what they did.”

The widening gap between climate targets and the current landscape of the energy sector should worry us all.

Read our latest issue of Trade Finance Talks, May 2022