Asian emerging markets (Asian EMs) have been the bedrock of global growth for almost a decade.

Between 2010 and 2020, developing and emerging Asian economies, as categorised by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), grew by a cumulative 113%.

This was far above the 28% growth posted by the global economy as a whole, and even further above the measly 17% growth posted by the G7.

In this context, it is clear that any regional downturn driven by capital flows back to the US could add much unwanted pressure to a potentially fragile global economy.

It can be argued that there are parallels between the expected economic environment of 2022, which may include US tapering together with moderate rate hikes, and the economic environment of 2013, with the shock that the taper tantrum sent through emerging markets (EMs).

However, such comparisons do not stand up to scrutiny, and in many respects we already know that the Fed’s new programme will not impact Asian EMs too severely.

The Fed advised of a wind-down in its asset purchases last year, and has reiterated its commitment to rate hikes. Yet to date, Asian EMs have not felt much pain.

In late November 2021, the Fed confirmed its tapering plans, but as of the time of writing, Asian EM currencies have barely moved on average.

However, and importantly, the Chinese yuan renminbi (CNY) appreciated by 2.2% against the dollar, highlighting its growing appeal.

Bond yields tell a similar story. Over the last six months, two-year spreads increased by an average of 78 basis points.

Removing Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, the two clear outliers from the basket, two-year bond yields increased on average by only 10 basis points, while in China two-year yields decreased by 31 basis points.

This is against a widening of the US two-year yield by 83 basis points.

One narrative to explain the divergence between 2013 and the present day might be that the Fed has actually managed the situation far better this time around.

By forward guiding over a longer period, it can be argued that the markets have acted in a less reactionary manner.

However, this would do a disservice to a shifting economic landscape in which Asian EMs are taking centre stage, and in which China has the star role.

There are three key factors which suggest that there has in fact been a more fundamental transition since 2013 that cannot be explained by just forward guidance alone.

First, there has been the rise of China as a legitimate potential superpower, and the increasing likelihood that its currency will reach reserve status over the medium term.

Secondly, inflationary pressure means real rates in the US might not be attractive until we see more price stabilisation.

Finally, many Asian EMs have strengthened significantly from a macro-economic perspective since the early 2010s.

China and the US

While the US’s status as superpower remains intact, the implications of the 2008 financial crisis and the required fiscal and monetary response to COVID-19 has moved the US into the final phase of its available economic tool set.

In what legendary hedge fund manager Ray Dalio has termed ‘MP3’ (monetary policy 3), the normal tools of MP1 (interest rates) and MP2 (quantitative easing) have now lost their ability to properly stimulate the economy, given that they have been fully exhausted.

The last remaining tool in the arsenal for the US is to reflate the economy through an increase in the availability and quantum of money.

It could print more money to supply US government debt in order to increase spending, or simply print money and give it to the government and citizens to spend.

However, broadly speaking, such action would decrease the willingness of others (investors, countries, individuals) to hold that currency over the longer term, as depreciation and real returns become less attractive given the inflationary dynamics that would persist in such an environment.

Meanwhile, China is on the rise, and is in fact only at the beginning of its ascendency.

Moreover, China still has most of the available fiscal and monetary tools at its disposal to stimulate the economy if required.

Lending, investing, and insuring in China are not without their risks, however, as evidenced by the current real estate crisis – although the belief is that China has a government system that is capable of supporting sectors in a targeted manner.

That said, China is very, very far from achieving the kind of reserve currency status enjoyed by the US, or indeed having the legal structures in place that give foreign investors and lenders the protection they require.

According to the IMF’s measure of claims in different currencies, as of Q3 2021, the US dollar had 40x more claims against it than the Chinese renminbi.

It is a long road for China before it takes over from the US’s exorbitant privilege, but looking at the trends is also important.

Claims on the dollar have increased by 20% over the last five years, whereas claims against the renminbi have increased by 250%.

China’s status as the third financial powerhouse house alongside the US and EU is a matter of when, not if.

Asian EM strength

While China may get most of the attention when considering Asian EMs, it is important to note the relative strengths and weaknesses in other countries in the region.

Through assessing a nation’s reserve adequacy, it is clear which countries have maintained sound external reserve balances, and which may find themselves facing difficulties if real US interest rates became sufficiently attractive.

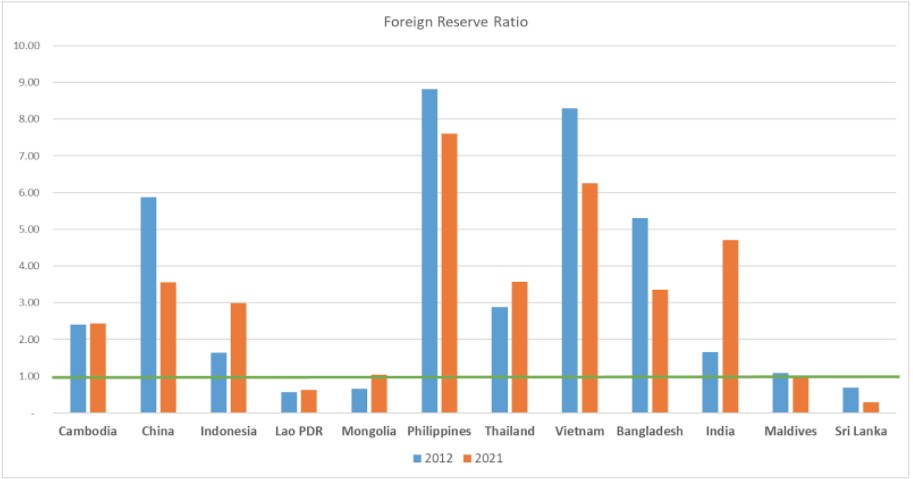

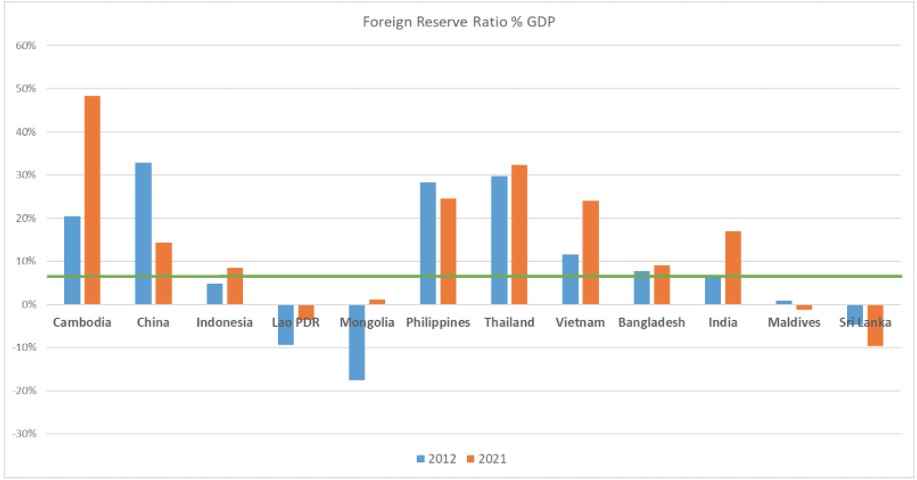

The following graphs measure two different ratios using the same metric.

Reserve adequacy measures a country’s foreign exchange reserves against their external short-term debt, together with the current account deficit/surplus.

A country with a ratio of less than one may struggle to fund its external balances, for instance, if foreign currency debt markets were no longer accessible for an extended period of time.

It would be further advisable that an EM hold reserves beyond this level in case it also has to defend its currency.

Moreover, a 2021 Dallas Fed study showed that there is an inflection point when measuring this reserve surplus/deficit against a country’s GDP.

The study found that a reserve adequacy below 7% of GDP suggested a higher likelihood of currency depreciation, yield spread increases, and interest rate hikes, in the event of more attractive yields in the US.

Cambodia, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam have all strengthened materially since 2012 with the Philippines and Thailand maintaining high levels of reserve adequacy.

In the final analysis, there is a potential threat to some Asian EMs, should there be a meaningful increase in US rates.

In particular, Laos, Mongolia, the Maldives, and Sri Lanka are most at risk from a shifting economic environment, and would be hit hard should investors and lenders take a negative stance.

Overall, the threat to the region as a result of Fed action has greatly diminished, and indeed the Fed may well not be able to increase rates by as much as is necessary, particularly if, for example, stagflation becomes a serious concern.

In that hopefully unlikely scenario, it would be the Fed – not the Asian EMs – facing a decisive moment.