Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

Canada can leverage its remarkable cultural diversity to drive a similar diversity in the suppliers to its many industries and thus encourage a more inclusive economy. In doing so, it can help illuminate a pathway for other diverse countries and help power economic growth, social stability, and general prosperity.

What is supplier diversity?

As per The Conference Board of Canada, a diverse supplier is a business that is at least 51% owned, operated, and controlled by either women, members of an indigenous community (for example, First Nations, Inuit, or Metis people), members of a visible minority group or members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ2+) community.

Supplier diversity allows diverse firms, often small businesses, to enhance existing jobs, create new ones, increase income and wages, and contribute more to tax revenue, thereby promoting economic growth in both the local community and the broader economy.

Current landscape in Canada

Despite Canada’s multiculturalism — a policy that began in the 1970s and has evolved — efforts to encourage diversity in suppliers have only gained momentum in recent years, while it has been a long-standing tradition in the United States.

The latter’s lead in this area can be traced back to the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s that led to legislation during the administration of President Richard Nixon in the early 1970s.

Canadian suppliers face several core challenges, including a lack of mandates, awareness, capital, and resources. And until recently the country’s stated goals or targets have been limited, except for a 5% target in procurement for indigenous suppliers.

As such, they have failed to signal to the market that it should promote policies to encourage supplier diversity. Incentives that are in place requiring diverse procurement initiatives are inadequate, and often too narrow in scope or reach, such as the Atlantic Accord for oil and gas resource management in the Maritime provinces on the Atlantic coast.

Nonetheless, recent initiatives are making headway. These include the Women Entrepreneurship Strategy aimed to boost financing, talent, network, and expertise for women-owned businesses. Similarly, the rollout of financing by the Federation of African Canadian Economics, which administers the Black Entrepreneurship Fund, has driven wealth creation for black-owned businesses.

Investment in the 2SLGTBQI+ Entrepreneurship Program has enabled businesses from that community to benefit from business scale-up, ecosystem funds, and knowledge hubs. These government advancements will be pivotal in reducing barriers and building a more inclusive economy.

Awareness is another issue.

Many companies perceive the inclusion of diverse suppliers to be impractical due to perceived costs and timing issues surrounding certification. Even once the right suppliers are found, these may face difficulties due to undercapitalisation and limited capacity to deliver goods and services to geographically dispersed companies.

With more dialogue emphasising the benefits and opportunities of supplier diversity, leaders of companies are taking a hands-on approach to get suppliers accredited and streamline processes to get new suppliers on board.

They have observed that increasing representation will aid in job creation, community development, and wealth distribution. The alignment of company strategy with supplier diversity under the broader umbrella of corporate social responsibility, rather than operating in a separate group, will be important in extending touch points for greater impact.

Access to financing and mentorship programmes has been likewise inadequate, leaving smaller suppliers without operational expertise to build business capabilities and networks to foster strong relationships with various levels of government and companies.

New efforts are giving impetus to get certifying organisations to accredit suppliers, connect companies, and deliver training via networking events and activities.

For example, the Supplier Diversity Alliance Canada supports and informs governments, companies, and relevant stakeholders about the significance of inclusive procurement policies and practices. Under the alliance, specialised organisations — the Canadian Aboriginal and Minority Supplier Council, the Canadian Gay and Lesbian Chamber of Commerce, and the Inclusive Workplace and Supply Council of Canada — will continue to play a critical role in exposing suppliers to unique opportunities and contracts.

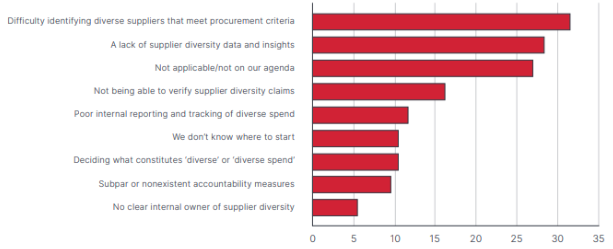

Figure 1: Supplier Diversity Barriers Globally

Supplier diversity as a growth lever

By advancing supplier diversity programmes, companies will improve competitiveness, broaden access to new markets, and enrich their reputations.

To improve competitiveness, governments and companies can minimise concentration risk by working with additional suppliers from a qualified pool, enhancing product and service quality, and driving down costs.

A wider supplier base will also enable companies to have resilient and agile supply chains to deal with unforeseen events. For example, the City of Toronto paved the way to supplier diversity by forming a strategy to include low-dollar value contracts, giving diverse suppliers, usually smaller, the chance to participate in government procurement.

In broadening market access, working with diverse suppliers provides a gateway for companies to enter new markets, opening new sources of revenue. Moreover, such practices encourage consumers to buy.

A survey by The Female Quotient in partnership with Google and Ipsos, examining how inclusive ads affect consumer behaviour, revealed that 64% of those surveyed would take some sort of action after seeing an ad they considered to be diverse or inclusive. This percentage was even higher among underrepresented groups.

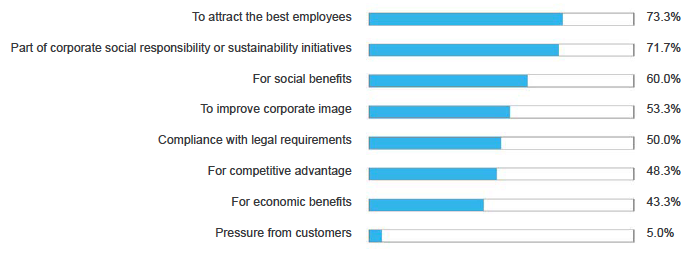

Companies with supplier diversity programmes, meanwhile, are more likely to attract and retain diverse employees as they can see their employers prioritising diversity, equity, and inclusion practices in the workplace.

This would translate to higher positions in key rankings, such as Canada’s Best Diversity Employers by Mediacorp, Forbes’s Canada’s Best Employers for Diversity, HRD’s The Most Diverse and Inclusive Companies in Canada etc.

Figure 2: Supplier Diversity Drivers in Canada

In short, supplier diversity programmes can be part of broader efforts to overcome socioeconomic issues including discrimination or prejudice. At the same time, they can yield financial and non-financial benefits to the companies that embrace them.

The future of supplier diversity is undoubtedly global. It fits into the S category of the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) equation. It’s about more than being suitable for ESG; businesses have an upside in doing the right thing.

Recent developments have shown that mutually beneficial relationships can generate value if stakeholders continue to build on the early foundations. This can be achieved with appropriate incentives, measures of success, and accountability.

By weaving social responsibility and strategic business practices and tailoring their implementation by factoring the local social, cultural, and economic contexts with global supply chain partners, Canadian businesses can help drive innovation, foster social equity, and create an inclusive future for all.

Note: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any organisation.