Force Majeure

Access trade, receivables and supply chain finance

We assist companies to access trade and receivables finance through our relationships with 270+ banks, funds and alternative finance houses.

Get StartedContents

Following the global COVID-19 outbreak, businesses worldwide have grappled with the impact on their contractual obligations. Amidst this uncertainty, questions arise regarding the classification of COVID-19 as a force majeure event and its implications on relieving contractual obligations. This article illuminates the essence of force majeure events and underscores the significance of meticulously crafted force majeure clauses in commercial contracts.

Introduction to Force Majeure Clauses in International Commercial Contracts

Force majeure clauses are common clauses in commercial contracts and their purpose is to excuse parties from liability in the event of an unforeseeable and unavoidable occurrence. The term force majeure emanates from French civil law and it means “superior force”.

However, under common law or English law, the doctrine of force majeure does not exist. Instead, it is up to the parties in a contract to decide what amounts to force majeure and what the consequences should be if a force majeure event occurs. Generally, force majeure clauses will relieve parties to a contract of performance of their contractual obligations in the event of an occurrence outside the control of the parties.

Force majeure and protecting your business in the face of Covid-19

TFG heard from Mayer Brown’s Ashley McDermott, giving a legal perspective on force majeure and protecting your businesses given the uncertainties around covid-19

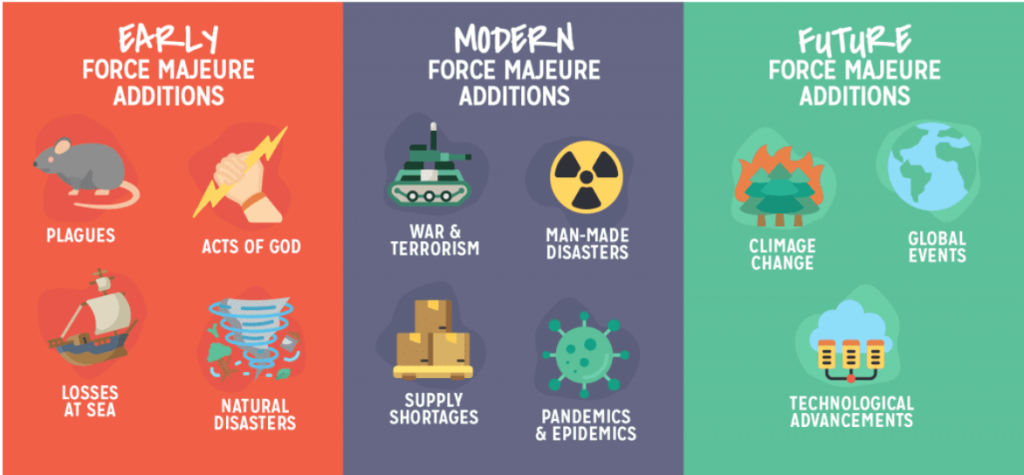

Force Majeure Events

A force majeure event is an unexpected event that prevents the performance of a contractual obligation. Usually, these are events that are beyond the parties’ control and could not have been foreseen or prevented by the parties at the time the contract was been entered into. Examples of such events include natural disasters, war, terrorism, government actions, riots and strikes.

A well drafted force majeure clause will define that force majeure event that will trigger the application of the clause. There are two approaches in defining force majeure events. The first approach involves having an exhaustive definition which lists all possible events that are intended to be covered under the contract by the parties. This approach is risky because the parties may not be protected by the force majeure clause if an unanticipated event that was not considered at the time of drafting the clause occurs. The second approach is to have a generic and wide definition of a force majeure event as any event or circumstances that are beyond the reasonable control of the party seeking to rely on the clause.

Is COVID-19 a Force Majeure Event?

The COVID-19 outbreak is an unprecedented event that may not have been foreseen by many people when drafting their contracts. Whether it is a force majeure event or not remains a matter of interpretation and application of the contract in question. The impact of the outbreak in the performance of contractual obligations must be assessed based on each individual case.

Since the outbreak was unforeseen, it is unlikely that most force majeure clauses in existence now specifically envisaged COVID-19. However, there may be a reference to events like a “national emergency”, “pandemic”, epidemic” or “disease” as force majeure events. It is, therefore, possible to argue that the COVID-19 outbreak constitutes one or more of these events.

Many force majeure clauses will have included events like compliance with a law or a government directive or regulation. We have seen many governments around the world issue directives such as restrictions on movement. The effect of these directives and regulations need to be analysed to determine whether the outbreak can be considered as a force majeure event.

Importance of Force Majeure Clauses in Contracts

The importance of these force majeure clauses in commercial contracts cannot be gainsaid. Under English contract law, parties have the freedom to set out all the terms that will govern the performance of their contractual obligations.

The freedom and flexibility of setting the terms of the contract also guarantees the parties that those terms will not be altered or changed by other legal principles existing outside of the contract. This freedom to set the terms by parties also gives them an opportunity to protect their contract from unavoidable circumstances that may occur during the term of the agreement.

It is therefore common practice for parties to include force majeure clauses in their contracts to relieve any party from performance of its contractual obligations if performance is affected by events outside its control.

Claiming Relief Under Force Majeure

A party seeking relief under a force majeure clause must comply with certain requirements before invoking this clause. First, the affected party must comply with any procedural requirements provided for under the contract. These requirements include the requirement to issue the other party with a notice that the force majeure event is affecting the performance of its contractual obligations. This notice must be given within the stipulated time frame. The notice requirement will usually be a condition precedent to be fulfilled by the party seeking relief under this clause.

Further, a party seeking relief must demonstrate other things for them to be excused from performing their contractual obligations. The party invoking the force majeure clause must demonstrate that it was prevented, hindered or delayed from performing its contractual obligations as a result of the force majeure event.

The party must show that it was legally or physically impossible to perform its obligations as a result of the force majeure event. The party must also demonstrate that failure to perform its obligations was as a result of circumstances or events beyond their control. Also, the party seeking relief must also show that there are no reasonable steps it could take to avoid the unforeseen event or to mitigate the consequences of the event.

Most force majeure clauses will require a party to take all reasonable steps to mitigate the effects of a force majeure event. To successfully invoke this clause then the party must demonstrate that it indeed made reasonable efforts to reduce the effects of the force majeure event on the performance of its obligations.

Effects of a Force Majeure Claim

The consequences of invoking a force majeure clause will depend on the drafting of the contract. Generally, the effect of invoking the force majeure clause is that one or more of the parties will be excused from performing its obligations under the contract. That party will therefore be relieved of liability for failure to perform its obligations sometimes without damages or costs being payable.

Another effect of a force majeure event is to mutually suspend the performance of obligations under the contract or to extend time required in the performance of the obligations in the event of continued delay or non-performance of obligations. These obligations will then resume once the force majeure event ends or is over.

Invoking the force majeure clause may also terminate the contract. Liability for non-performance of the obligations will be extinguished because the contract has been terminated. Usually there will be procedural steps to follow, like serving of notices to effect this termination. Termination of the contract may be commercially beneficial to the parties as it gives them room to renegotiate the contract.

Implementing force majeure clauses

Force majeure clauses serve as vital provisions in contracts, offering relief to parties when unforeseen events hinder their ability to fulfil contractual obligations. By including these clauses, parties can mitigate the risks associated with circumstances beyond their control. In this article, we present our top 10 tips for implementing force majeure clauses in commercial contracts, providing guidance to ensure their effectiveness and protect the interests of all parties involved.

- Include force majeure clauses:

The first and foremost tip is to include explicit force majeure clauses in your contracts. Without such provisions, limited remedies are available in situations where it becomes impossible to perform the contract.

- Consider the beneficiary:

During contract negotiations, carefully consider who the force majeure clause is likely to benefit more: you or your counterparty. Suppliers generally seek to invoke force majeure clauses, so it is in their interest to ensure the clause’s scope encompasses a broad range of force majeure events. As a supplier, you may want to expressly state that the clause does not relieve the customer of their payment obligations.

- Define force majeure events:

Given the absence of an agreed-upon definition, it is crucial to carefully define what constitutes a force majeure event in the contract. Typically, such events refer to acts, circumstances, or events beyond the reasonable control of the party involved. Including specific examples of force majeure events and a catch-all provision will provide clarity and help avoid ambiguity.

- Address breach of contract:

To rely on a force majeure clause, it is essential to have an express provision that allows you to suspend performance or terminate the contract in case of the other party’s breach. Without such provision, the force majeure clause cannot be invoked.

- Consider foreseeability:

If the force majeure clause does not explicitly state that the event must be unforeseeable or beyond a party’s control, it will not be implied. Case law demonstrates that foreseeable events are typically within the relevant party’s control regarding their ability to fulfill contractual obligations. Address foreseeability explicitly in the drafting of the clause.

- Establish a causal link:

To rely on a force majeure clause, there must be a direct causal link between the force majeure event and the party seeking to invoke the clause. The inability to perform contractual obligations must be a direct result of the force majeure event specified in the contract.

- Determine the impact on performance:

The wording of the force majeure clause often determines the extent to which a party’s obligations must be affected. If the clause requires that the force majeure event renders performance legally or physically impossible, it sets a higher threshold than a clause that considers hindrance or delay. Clarify the specific impact required for the force majeure clause to be triggered.

- Understand the effect of the clause:

The effect of a force majeure clause depends on its drafting. It may result in the suspension of contractual obligations for the duration of the event, termination of the agreement after a certain period, or an automatic right to terminate. Clearly define the consequences in the clause.

- Check the notice requirements:

Review the contract to identify any notice requirements associated with invoking the force majeure clause. Some contracts necessitate prompt notification to the counterparty upon the occurrence of a force majeure event. Comply with these notice provisions to ensure timely communication.

- Negotiate and mitigate:

Before invoking the force majeure clause, consider engaging in informal discussions with your counterparty to explore alternative arrangements that can mitigate the impact of the force majeure event. Maintaining open communication and attempting to find mutually agreeable

Doctrine of Frustration

As earlier indicated, the concept of force majeure does not exist under English law. In the event a contract does not have a force majeure clause, parties can rely on the English law doctrine of frustration if the performance of their contractual obligations has been affected by an unforeseen event.

The doctrine of frustration allows a contract to parties to terminate a contract when their contractual obligations cannot be performed as a result of an unforeseen event or circumstance which is beyond the control of the parties.

Frustration is meant to avoid an injustice where there has been a major change in the circumstances surrounding the contract and neither party is at fault. A change in the law that makes it illegal for one of the parties to perform its contractual obligations could be considered as a frustrating event since no party is at fault.

A contract will terminate automatically when a frustrating event occurs and such an event is unexpected or unforeseen and beyond the parties’ control. The event must also make performance of the contractual obligations impossible or totally different from what the parties in the contract envisaged at the time of entering the contract.

All three elements must be present before a contract can be terminated under frustration. The frustrating event must significantly change the nature of the contractual obligations required of each party.

Frustration of a contract requires a higher threshold to be met before a contract can be considered as frustrated and therefore terminated. A simple difficulty or an economic inconvenience in performance of an obligation is not sufficient to frustrate the contract. In cases where the physical subject matter of a contract has been destroyed or in cases of personal contracts where the person who is supposed to perform the contract has died then the contract can be considered frustrated.

Frustration appears to be similar to force majeure but the consequences of each are different. Where a contract has been frustrated, then the parties are released from the obligations completely. The doctrine of frustration does not allow the performance of contractual obligations to be suspended or granted an extension of time as is the case under force majeure.

The contract is terminated immediately as it becomes evident that it has been frustrated. If the contract has been terminated under frustration, parties can recover any amounts of money paid under the contract before it was frustrated.

Does COVID-19 Constitute Frustration?

The question as to whether the COVID-19 outbreak can frustrate your contract is a matter to be determined by analysing the terms and circumstances of each contract individually. The key question to be answered is whether the outbreak of COVID-19 makes the performance of your contractual obligations impossible or just more difficult. If the outbreak makes performance of your contractual obligations more difficult to perform then that will not result in the contract being frustrated. If there are increased costs in the performance of an obligation or delays in that performance, then the contract will not be considered as frustrated.

Conclusion

Many businesses with contractual obligations are facing unprecedented difficulties in performing those obligations during this COVID-19 pandemic. The question on the minds of many decision makes right now is whether they should invoke the force majeure clauses in their contracts. Whereas there is no specific answer to that question, there is a need to carefully consider the circumstances of each and every case.

It is recommended that specialist legal advice be sought before making any decision to invoke a force majeure clause or terminating a contract as a result of frustration. Some of the considerations to be made before such a decision is made include the consequences of terminating the contract on the business stakeholders e.g. suppliers, customers, shareholders and employees.

Parties need to consider their options before invoking a force majeure clause. Suspension of performance obligations may be a good solution if the parties intend to retain their contractual relationship in the future.

Parties in the contract may consider other alternatives in the performance of their obligations. This could be seeking alternative suppliers and finding means of reducing delays or minimising losses incurred.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution that can be prescribed in such a situation as there are no two contracts or force majeure clauses that are the same. Parties should take time now to review their current contracts and identify ways to potentially reduce and mitigate risks as a result of this pandemic.

- International Trade Law Resources

- All International Trade Law Topics

- Podcasts

- Videos

- Conferences