Free on Board FOB (FOB) Incoterms® 2020 Rule

Contents

Free on Board FOB – Incoterm® 2020 Rules [UPDATED 2024]

FOB (Free on Board) is the most commonly used trade term, but in practice, it is used without reference to any version of the Incoterms® rules.

In such cases, it is then up to the seller and buyer to agree in their contract on what they mean when they use these three letters.

Introduction to Free on Board (FOB)

FOB has its origins in the days of sailing ships.

In the Incoterms® 2020 rules, as in previous versions, FOB requires the seller to place the goods on board the vessel nominated by the buyer. From that point on risk of loss or damage to the goods transfers to the buyer. “On board” is no longer defined as placing the goods “across the ship’s rail” and, in fact, is not defined any further as it will be a matter for the contract to specify depending on the nature of the goods.

The buyer is responsible for the costs of transport from the named port of shipment, the duties, tariffs and taxes for import customs and any additional transportation costs to the final destination. The seller must cover the costs of transporting the goods to the named port, loading the goods on board the named vessel, and clearing the goods for export (including any fees or charges).

Since it is the buyer who contracts for carriage, the “shipper” on the bill of lading should be the buyer, not the seller.

The seller will most likely require at least a mate’s receipt or some other form of evidence of export (such as a copy of the bill of lading) for their VAT/GST purposes.

Often, where a letter of credit is involved, the seller is shown on the bill of lading as the “shipper”, in which case the seller would be wise to inform themselves of the additional liabilities they might be taking on under the terms and conditions of the bill of lading.

Free on Board (FOB) Incoterms 2020 rule – introduction, history, and uses

“Free on Board” has been in use since the sailing ship days. It was, of course, included in the first version of Incoterms® in 1936 and has remained identical in concept throughout the later versions.

The requirement is that the buyer must contract for the vessel or space on the vessel, and the seller must load the goods onto that vessel.

Interestingly, the delivery requirement was that the seller must simply deliver the goods on board, but the cost split was that the seller bears all costs and risks until the goods have “passed over the ship’s rail”. For decades this wording caused confusion and lawyers’ fees.

How do the costs and risks get split at the point while the goods are suspended above the ship’s rail? The 2010 version finally aligned the cost and risks matter with delivery, eliminating mention of the ship’s rail.

An interesting provision that has been in the Incoterms® rules ever since the 1990 version has been that the seller must arrange for shipment at the buyer’s cost and risk on the “usual terms” if it is so agreed in the contract. Sellers, however, should be wary of doing this. It will depend on the customary procedures in the relevant countries as to whether this is practical and desirable or could have unfortunate legal consequences for the seller.

The contract should lay out very specifically what is required of the seller and limit their liability if they are to be declared as the shipper or consignor. This provision seems a little at odds with how FOB is supposed to work. Whether it has a place now in the world of sea transport is a good question.

Use of FOB

FOB is not appropriate for container shipments under the Incoterms® 2020 rules. This is because, in container shipments, the cargo is given to the carrier at a place some distance from the port, such as a container yard or even the seller’s premises. As such, the seller does not load them “on board” the vessel and another term (like FCA) would be preferable in this situation.

It must also be pointed out that the peculiarly North American concept of “FOB shipping point, freight prepaid”, “FOB destination”, and “FOB destination, freight prepaid” have no place in international trade or domestic trade anywhere else.

As the Incoterms® 2010 and now 2020 rules are very much intended to apply to both international and domestic trade, it is hoped that all manner of strange local rules will die out.

Free on Board (FOB) podcast

Free on Board (FOB) seller and buyer obligations

FOB A1 / B1 general obligations

A1 (General Obligations)

In each of the eleven rules, the seller must provide the goods and their commercial invoice as required by the contract of sale and any other evidence of conformity, such as an analysis certificate that might be relevant and specified in the contract.

Each of the rules also provides that any document can be in paper or electronic form as agreed in the contract, or if the contract makes no mention of this, then the rules default to what is customary.

The rules do not explicitly define what “electronic form” is. This ambiguity means that it can be anything from a .pdf file to a blockchain record or another format yet to be developed.

B1 (General obligations)

In each of the rules, the buyer must pay the price for the goods as stated in the contract of sale.

The rules do not refer to when the payment is to be made (e.g., before shipment, immediately after shipment, thirty days after shipment, etc.) or how it is to be paid (e.g., prepayment, against an email of copy documents, on presentation of documents to a bank under a letter of credit, etc.).

These matters should be specified in the contract.

FOB A2 / B2: delivery

A2 (Delivery)

Under FOB, the seller “delivers” by placing the goods on board the vessel nominated or provided by the buyer on the agreed date, or within the agreed period as notified by the buyer, or, if there is no such time notified, then at the end of that period.

There is still a belief that the ship’s rail is the defining point for delivery under FOB (i.e., before the notional vertical line above the rail is the seller’s cost and risk and after is the buyer’s cost and risk).

A court ruled that the delivery point was when the goods were on the deck, but that then caused the question: was the notional vertical line replaced with a notional horizontal one in line with the deck itself and what if the goods were being placed below deck?

This ship’s rail concept was removed in the Incoterms® 2010 version, and now, “on board” is typically taken to mean when the goods are safely on the deck or in the hold.

If the cargo needs to be then further secured for transportation – such as being lashed or separated with some material or spread evenly throughout the hold for bulk goods like grain – the seller and buyer should agree in their contract what is needed and at whose cost and risk this is done.

B2 (Delivery)

The buyer’s obligation is to take delivery when the goods have been delivered, as described in A2.

FOB A3 / B3: transfer of risk

A3 (Transfer of risk)

In all the rules, the seller bears all risks of loss or damage to the goods until they have been “delivered” in accordance with A2 described above.

The exception is loss or damage in circumstances described in B3 below, which varies depending on the buyer’s role in B2.

B3 (Transfer of risk)

The buyer bears all risks of loss or damage to the goods once the seller has delivered them as described in A2.

If the buyer fails to inform the seller of where and when the vessel will be presented, if the vessel fails to arrive on time, or if it fails to take the goods so that the seller cannot deliver, then the buyer bears the risk of loss or damage to the goods from the agreed date or at the end of the agreed period.

FOB A4 / B4: carriage

A4 (Carriage)

Under FOB, the seller has no obligation to contract for carriage.

If the buyer requests it, the seller (at the buyer’s risk and cost) must provide the buyer with any information known by the seller, including transport-related security requirements, that the buyer needs to arrange carriage.

If agreed, the seller must contract for carriage (at the buyer’s risk and cost) on the usual terms, which are usually agreed upon in the contract or determined by previous dealings between the parties.

The seller must comply with any transport-related security requirements but only up to delivery.

B4 (Carriage)

The buyer must contract for carriage from the port of shipment, except if it is agreed that the seller makes the contract of carriage as described in A4.

FOB A5 / B5: insurance

A5 (Insurance)

The seller does not have the risk beyond the delivery point, so it has no obligation to the buyer to arrange a contract of insurance.

However, if the buyer requests (at its risk and cost), the seller must provide the buyer with information in its possession that the buyer needs to arrange its insurance.

B5 (Insurance)

Despite having the risk of loss or damage to the goods from the delivery point, the buyer does not have an obligation to the seller to insure the goods.

Whether the buyer chooses to insure the goods or bear the risk themselves is entirely their choice.

FOB A6 / B6: delivery / transport document

A6 (Delivery / Transport document)

Under FOB, the seller (at its own cost) must provide the buyer with the usual proof that the goods have been delivered in accordance with A2.

Unless this proof is a transport document, then the seller must assist the buyer (at the buyer’s request, risk, and expense) to obtain a transport document.

In practice, it is often the seller who will arrange with the buyer that the proof is an “on board” bill of lading showing the seller as the shipper/consignor. Alternatively, it can be a simple mate’s receipt issued by the vessel’s master.

B6 (Delivery / Transport document)

The buyer must accept the proof of delivery provided by the seller.

FOB A7 / B7: export / import clearance

A7 (Export / Import clearance)

FOB, like all the multimodal rules, is suitable for both domestic and international transactions.

Under FOB, the seller must (at its own risk and expense) carry out all export clearance formalities required by the country of export, where applicable, such as:

- licences or permits,

- security clearance for export,

- pre-shipment inspection, and

- any other authorisations or approvals.

The seller has no obligation to arrange any transit/import clearances.

However, if the buyer requests (at its own risk and cost), the seller must assist in obtaining any documents or information that relate to formalities required by the country of transit or import, such as:

- permits or licences,

- security clearance for transit/import,

- pre-shipment inspection required by the transit/import authorities, and

- any other official authorisations or approvals.

B7 (Export/ Import clearance)

Where applicable, the buyer must assist the seller (at the seller’s request, risk, and cost) in obtaining any documents or information needed for all export-related formalities required by the country of export.

Where applicable, the buyer must carry out and pay for all formalities required by any country of transit and the country of import. These include:

- licences and permits required for transit,

- import licences and permits required for import,

- import clearance,

- security clearance for transit and import,

- pre-shipment inspection, and

- any other official authorisations and approvals.

These are the buyer’s responsibility because they occur after “delivery” by the seller.

At first glance, it might seem strange that both seller and buyer are responsible for pre-shipment inspections. To clarify, the seller is responsible if it is a requirement of the country of export, and the buyer is responsible if it is a requirement of the country of transit/import.

FOB A8 / B8: checking / packaging / marking

A8 (Checking / Packaging / Marking)

In all rules, the seller must pay the costs of any checking operations which are necessary for delivering the goods, such as checking quality, and measuring, packaging, weighing, or counting the goods.

The seller must also package the goods (at its own cost) unless it is usual for this particular good to be sold unpackaged, such as in the case of bulk goods.

The seller must also take into account the transport of the goods and package them appropriately unless the parties have agreed in their contract that the goods be packaged or marked in a specific manner.

B8 (Checking / Packaging / Marking)

In all rules, there is no obligation from the buyer to the seller regarding packaging and marking. There can, in practice, however, be agreed exceptions, such as when the buyer provides the seller with labels, logos, or similar.

FOB A9 / B9: allocation of costs

A9 (Allocation of costs)

The seller must pay all costs until the goods have been delivered under A2 (meaning loaded on board the vessel for FOB) except any costs the buyer must pay as stated in B9.

Under FOB, the seller has to pay:

- any costs involved in providing the usual proof that the goods have been delivered, so if the contract between the parties states that proof is a bill of lading, then the seller pays any document fee,

- any costs, export duties, and taxes, where applicable, related to export clearance.

Further, if the seller requests that the buyer provide any information or documents in relation to customs clearance, then the seller must pay the buyer for these costs.

B9 (Allocation of costs)

Under FOB, the buyer must pay:

- any duties, taxes and other costs for transit or import clearance, where applicable,

- all costs relating to the goods from when they have been “delivered” (meaning loaded on board the vessel for FOB), other than those payable by the seller

If the buyer has requested the seller to provide assistance in obtaining information or documents needed for the buyer to effect loading on board, carriage, import formalities, insurance, and transport documents, then the buyer must reimburse the seller’s costs.

Additionally, if the seller has advised that the goods have been clearly identified as the goods under the contract, the buyer pays any additional costs that arise from:

- the buyer failing to nominate the vessel,

- the vessel failing to take the goods from the seller, or

- the vessel closing for cargo earlier than when the buyer notified the seller.

FOB A10 / B10: notices

A10 (Notices)

The seller must give the buyer sufficient notice that the goods have been delivered (meaning loaded on board) or that the vessel failed to take the goods within the time agreed.

This could occur, for example, when the agreed delivery period was March and the vessel arrived in the load port on 31 March but only allowed loading on 1 April.

B10 (Notices)

The buyer must give sufficient notice to the seller of:

- any transport-related security requirements and

- the vessel’s name and loading point within the port of loading.

These would usually be specified in the contract.

Using Free on Board for container shipments

Unfortunately, sellers and buyers commonly treat FOB as merely a price point – the seller doesn’t pay the freight, and the buyer does.

Freight forwarders treat it as a way that they know the seller pays local charges in the export country, freight is marked as “collect” on the transport document and paid by the buyer. Often, their instruction forms to be completed and signed by the seller will only show three or four options, and FOB always features whether the goods are being transported by container or by air.

The simple fact is that in the vast majority of transactions handled by freight forwarders – i.e., LCL (less than container load), FCL (full container load), or air – FOB should not be an option.

Clarifications to FOB use over the years

Incoterms® 1990, in its preface for FOB, stated, “When the ship’s rail serves no practical purpose, such as in the case of roll-on/roll-off or container traffic, the FCA term is more appropriate to use.”

In the Incoterms® 2000 rules, FOB had a one-paragraph preface that included, “If the parties do not intend to deliver the goods across the ship’s rail, the FCA term should be used.”

Then, the 2010 version strengthened this concept by splitting FAS, FOB, CFR, and CIF off into their own section as “Rules for Sea or Inland Waterway Transport” and included an even stronger explanation: “FOB may not be appropriate where goods are handed over to the carrier before they are on board the vessel, for example, goods in containers, which are typically delivered at a terminal. In such situations, the FCA rule should be used.”

Now, in the 2020 version’s Explanatory Notes for Users, the matter is even more clearly explained: “This rule is to be used only for sea or inland waterway transport where the parties intend to deliver the goods by placing the goods on board a vessel. Thus, the FOB rule is not appropriate where goods are handed over to the carrier before they are on board the vessel, for example, where goods are handed over to a carrier at a container terminal. Where this is the case, parties should consider using the FCA rule rather than the FOB rule.”

In container shipments, the seller does not put the goods “on board” the vessel

Why are the roles so set against using FOB for container shipments? Everybody does it. Why don’t the rules accommodate just it?

The answer is that the delivery point in the FOB Incoterms® 2020 rule is when the goods are delivered on board the vessel by the seller, and this is almost always impossible for the seller to do when the goods are containerised.

When the seller sells goods that will be shipped as a full container load (FCL), it either packs the container provided by the buyer’s carrier at its premises or delivers the goods to a facility nominated by the buyer’s carrier where they will be packed into the container. From there, the container may well be moved to a terminal or container yard (CY) contracted by the shipping line in the port, awaiting the arrival of the vessel to be loaded.

If the goods are less than a container load (LCL), they will be picked up from the seller by the buyer’s carrier or delivered by the seller to a container freight station (CFS) nominated by the buyer’s carrier where they will be consolidated with other goods into a container, which then moves as just described.

The seller has no direct control of, or knowledge of, what is happening to the goods once they leave the seller’s possession and are in the possession and control of the buyer’s carrier.

The seller certainly cannot deliver the goods on board the vessel.

Free on Board (FOB): advantages and disadvantages

Advantages for the seller

What are the advantages for the seller to use the FOB Incoterms® 2020 rule?

The most obvious is that when the goods have been delivered on board the buyer’s vessel, the seller has not only physically done what it has to do, but it might seem that it also has no further costs, risk of loss or damage to the goods, or responsibilities.

Well, that is not quite correct.

The seller must still (at its own cost) provide the buyer with proof that the goods have been delivered on board, whether that be a mate’s receipt, some other form of receipt, or a transport document such as a bill of lading. The seller must also assist the buyer with any information or documents the buyer will need for its import clearance formalities (at the buyer’s request, risk, and cost).

The most usual such document is the certificate of origin, but in practice, it is unusual for the seller to charge the buyer with the relatively insignificant cost of this.

Possible risks for the seller

Despite the seller not having any risk of loss or damage after delivery, a prudent seller would look at the agreed payment arrangements, which are outside the coverage of Incoterms® 2020.

What would happen if the buyer refused payment because it knew that the vessel had sunk? Or the market for that commodity has had a sudden downturn? What would happen if the buyer simply went bankrupt during the voyage?

Clearly, the seller would still have the risk of loss or damage to the goods, so the seller might like to investigate a contingency policy for marine cover.

From the buyer’s perspective

The benefit to the buyer is that it has control of the goods on the vessel it has arranged, and it has control of the costs as well.

The buyer has the risk of loss or damage to the goods from the point where they are delivered on board, and depending on the nature of the goods and their packaging, if any, it would be wise to detail in the contract precisely what this means.

For example, with bulk product poured into the holds, it would likely include the word “trimmed” to indicate that the load is evenly poured throughout the hold and relatively level at the top to distribute the weight correctly. For drums of product, it might include an agreement that dunnage, often scrap material, be provided to prevent the drums from moving and sliding and that they be lashed to hold them in place – what part does the seller have to play in these?

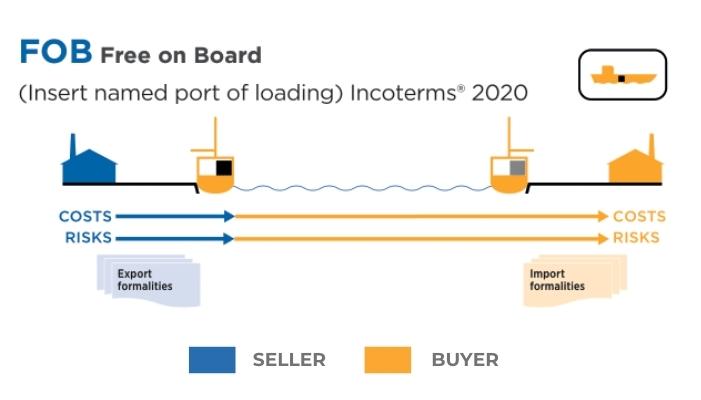

Free on Board (FOB) diagram 2024

Diagram: FOB – The seller must carry out all export formalities and the buyer must carry out import formalities. Source: ICC

Free on Board and letters of credit

Banks, in their letter of credit (LC) applications, are just as much at fault as forwarders for misleading their clients.

Their LC application forms almost invariably state three or four three-letter terms marked as “Incoterms”, and again, FOB features prominently, making buyers feel obliged to tick the FOB box even though their goods are containerised or by air.

Where does that leave the seller and buyer when they have agreed with each other to use the correct rule of FCA, but their bank insists on stating FOB because that is what is on their form and “we have always done it this way” or “this is our standard procedure”?

Banks cope very well with a true FOB Incoterms® 2020 transaction because it fits the way their application forms were designed decades ago, it fits very well with the way the LC rules – UCP600 – were written, and it fits very well with the SWIFT message standards for transmitting an LC in their MT700 format.

Nice and neat, a port of loading, a port of discharge, a latest onboard date, a requirement for a “full set of clean on board bills of lading marked freight collect….”

FOB Video – What are Incoterms® 2020 and why are they important?

“Incoterms” is a registered trademark of the International Chamber of Commerce.

Refer to ICC publication no. 723E for the text.

Publishing Partners

- Incoterms Resources

- All Incoterms Topics

- Podcasts

- Videos

- Conferences