FCA (Free Carrier) Incoterms® 2020 Rule

Contents

The Free Carrier (FCA) Incoterms® 2020 rule adds more onus to the seller, making them responsible for delivering the goods to a location the buyer nominates (when compared to Ex Works (EXW)).

Introduction to Free Carrier (FCA)

The Free Carrier (FCA) rule requires the seller to deliver the goods to the buyer or its carrier either 1) at the seller’s premises, loaded onto the collecting vehicle, or 2) delivered to another location (typically a forwarder’s warehouse, airport, or container terminal) not unloaded from the seller’s vehicle.

The seller must carry out any export formalities, and the buyer must carry out any import formalities.

FCA can be considered a step up from the largely unworkable EXW in that the seller is now responsible for physically handing the goods over, with the risk only being transferred to the buyer when delivery is made.

This rule works well for land transport within the European and Central Asian landmass because the truck collecting the goods will often be the same one transporting them to the final destination.

Free Carrier Incoterms 2020 rule – key changes and updates

While it is recommended in place of FOB for cross-ocean container shipments, in practice, FCA is largely unworkable in these situations.

This is because, in such shipments, the buyer only wants to bear the risk of damage or loss of the goods when they have actually been exported rather than having to deal with any problems in the exporting country.

The 2020 version introduced a new obligation on the buyer if agreed, to instruct its carrier to issue an on-board bill of lading. While well-intentioned and added mainly to deal with the seller’s need for letters of credit, this is not a well-thought-out provision and will fail in its execution.

It still considers “delivery” to be when the seller hands over the goods to the buyer’s carrier, meaning that the seller has no obligation to put the goods on board.

If anything were to happen to the goods between delivery and going on board it would technically be considered to be at the buyer’s risk. However, in reality, if this were to happen, the seller not be given an on-board bill of lading, and the buyer would not consider the goods exported and therefore refuse payment.

An unintended consequence would be that usually, the seller would end up being named as “the shipper” on that bill of lading, imposing on them liabilities that they neither knew about nor accepted.

It is also the only provision in the Incoterms® 2020 rules which requires a party to instruct a carrier yet gives no direct remedy to the other party should the carrier fail to act accordingly.

Free Carrier seller and buyer obligations

FCA A1 / B1 general obligations

A1 (General Obligations)

In each of the eleven rules, the seller must provide the goods and their commercial invoice as required by the contract of sale and any other evidence of conformity, such as an analysis certificate that might be relevant and specified in the contract.

Each of the rules also provides that any document can be in paper or electronic form as agreed in the contract, or if the contract makes no mention of this, then the rules default to what is customary.

The rules do not explicitly define what “electronic form” is. This ambiguity means that it can be anything from a .pdf file to a blockchain record or another format yet to be developed.

B1 (General obligations)

In each of the rules, the buyer must pay the price for the goods as stated in the contract of sale.

The rules do not refer to when the payment is to be made (e.g., before shipment, immediately after shipment, thirty days after shipment, etc.) or how it is to be paid (e.g., prepayment, against an email of copy documents, on presentation of documents to a bank under a letter of credit, etc.).

These matters should be specified in the contract.

FCA A2 / B2: delivery

A2 (Delivery)

The seller delivers in one of two ways:

1) If the named place is the seller’s premises

In this scenario, under FCA, the goods are considered to have been “delivered” when they have been loaded on the buyer’s provided transport. This can include the buyer’s carrier or its own vehicle if it is a domestic sale.

The term “loaded” generally implies that the goods have been safely positioned on the vehicle. However, securing tasks such as tying down or lashing pallets or crates loaded onto a truck falls under the vehicle driver’s responsibility, adhering to safety and traffic regulations. Conversely, if goods are placed into a container attached to the vehicle, it is reasonable to expect the seller to undertake the lashing and securing of the goods.

As in EXW, the seller must inform the buyer of any specific locations, such as its own warehouse, contract manufacturer, or a particular loading dock.

Furthermore, the seller must communicate any site-specific restrictions. For instance, if access to the loading dock is through a parking lot, it might be impractical for a forty-foot container on a trailer to navigate close to the dock.

2) If the named place is not the seller’s premises

In this scenario under FCA, the goods are considered to be “delivered” when the seller places them at the disposal of the buyer (or its carrier) at the specified place. The seller does not need to unload the goods.

The seller cannot be expected to provide the means to unload the goods into, say, a carrier’s terminal, nor would they be allowed to do so for safety, security, and insurance reasons.

This delivery must be made on:

1) the agreed date, or

2) at the time nominated by the buyer within the agreed period, or

3) failing these, at the end of the agreed period. (Why at the end? Before that, the buyer could still inform the seller of his desired time within the agreed period.)

B2 (Delivery)

The buyer’s obligation is to take delivery when the goods have been delivered, as described in A2.

Note that this rule does not discuss the means of transport at all. It merely mentions the carrier regardless of how the carrier will arrange the transport of the goods.

FCA A3 / B3: transfer of risk

A3 (Transfer of risk)

In all the rules, the seller bears all risks of loss or damage to the goods until they have been “delivered” in accordance with A2 described above.

The exception is loss or damage in circumstances described in B3 below, which varies depending on the buyer’s role in B2.

B3 (Transfer of risk)

The buyer bears all risks of loss or damage to the goods once the seller has delivered them as described in A2.

Additionally, if the buyer fails to have its carrier or another person give the required notice under B2, or that person fails to take the goods from the seller, then the buyer bears all risks either from the agreed date or time or if no agreed date or time, then at the end of the agreed period.

For example, suppose the contract states the delivery must occur in June. The seller has the goods ready at their premises to place on a buyer’s carrier’s truck, and that carrier informs the seller that they will collect the goods on 20 June.

If they do not actually collect them on this date, then the buyer bears the risk of loss or damage to the goods as of 30 June (the end of the contract period).

FCA A4 / B4: carriage

A4 (Carriage)

Under FCA, the seller has no obligation to the buyer to arrange carriage of the goods.

The seller, however, does have an obligation to provide the buyer with any information it has that the buyer requests, including any transport-related security requirements.

The seller is only responsible for any transport-related security requirements up to the moment of “delivery”. As such, if the seller trucks the goods to the carrier’s premises, the seller is only responsible for the transport-related security requirements for that leg of the journey.

In some instances, the seller and buyer can agree for the seller to contract for carriage. This might happen when the seller can obtain more favourable carriage rates than the buyer. Even in these instances, however, under FCA, carriage is at the buyer’s risk and cost.

While the rule states that the contract for carriage is to be “on the usual terms”, it is most likely that the two parties will agree in their contract precisely what those terms are.

B4 (Carriage)

Under FCA, the buyer must arrange for the carriage of the goods, whether by the buyer itself or a contracted carrier, at its own cost from the named place of delivery.

This allows the buyer to take delivery of the goods, as might occur in a domestic transaction. The exception is where, as stated in A4, the contract for carriage is arranged by the seller.

Note that the contract of carriage needs to be specific as to where it commences.

Remember that in A2, there are two places where the delivery can occur: either 1) at the seller’s premises loaded onto the collecting vehicle or 2) not unloaded from the seller’s vehicle at another place, which is typically the carrier’s premises.

FCA A5 / B5: insurance

A5 (Insurance)

Since the seller does not have the risk beyond the moment of “delivery” under FCA, it has no obligation to the buyer to arrange a contract of insurance.

However, if the buyer requests information from the seller that they need to arrange its insurance, the seller must provide it, albeit at the buyer’s risk and cost. If there is any information the buyer requests that the seller does not already know, the seller can, and probably would, choose to assist.

Nevertheless (and the Incoterms® 2020 rules do not cover this), a wise seller would investigate taking out marine insurance on a contingency basis. If the goods are lost or damaged in transit, causing the buyer to refuse to pay for them, the seller will want to have a fallback of being able to claim on its own marine insurance.

B5 (Insurance)

Despite having the risk of loss or damage to the goods from the delivery point, the buyer does not have an obligation to the seller to insure the goods.

Whether the buyer chooses to insure the goods or bear the risk themselves is entirely their choice.

FCA A6 / B6: delivery / transport document

A6 (Delivery/ Transport document)

Under FCA, the seller must provide the buyer with proof that the goods have been “delivered” in accordance with A2.

The exact form of proof is determined by both parties in the sales contract. It could be the buyer’s signature on a copy of the invoice, a forwarder’s cargo receipt or anything else that has been agreed.

If the buyer requests, the seller must assist the buyer, at the buyer’s risk and cost, in obtaining a transport document.

When the buyer directs their carrier to provide the seller with a transport document, such as a bill of lading or air waybill (under B6), and this document is negotiable (e.g., a bill of lading consigned to order in multiple originals), the seller must give the buyer a complete set of these original documents.

Typically, this occurs when the seller submits these documents, along with other shipping documents, to their bank under a letter of credit from the buyer’s bank.

B6 (Delivery / Transport document)

The buyer must accept the proof provided by the seller that the goods have been delivered as described in A2.

When the parties have agreed in their contract that the seller is to be given a transport document stating that the goods were loaded, such as an “on board” bill of lading, the buyer must instruct its carrier accordingly at the buyer’s cost and risk.

FCA A7 / B7: export / import clearance

A7 (Export / Import clearance)

FCA, like all the multimodal rules, is suitable for both domestic and international transactions.

Where applicable, the seller must (at its own risk and cost) carry out all export clearance formalities required by the country of export, such as licences or permits, security clearance for export, or pre-shipment inspection.

The seller has no obligation to arrange any transit or import clearances.

However, if the buyer requests it(at its own risk and cost), the seller must assist in obtaining any documents or information which relate to formalities required by the country of transit or import, such as permits or licences, security clearance, or pre-shipment inspection required by the authorities.

B7 (Export / Import clearance)

Where applicable, the buyer must assist the seller (at the seller’s request, risk, and cost) in obtaining any documents or information needed for all export-related formalities required by the country of export.

Where applicable, the buyer must carry out and pay for all formalities required by any country of transit and the country of import.

These include:

- licences and permits required for transit,

- import licences and permits required for import,

- import clearance,

- security clearance for transit and import,

- pre-shipment inspection, and

- any other official authorisations and approvals.

Under FCA, these are the buyer’s responsibility because they occur after “delivery” by the seller.

At first glance it might seem strange that both seller and buyer have responsibility for pre-shipment inspections. To clarify, the seller is responsible if it is a requirement of the country of export, and the buyer is responsible if it is a requirement of the country of transit or import.

FCA A8 / B8: checking / packaging / marking

A8 (Checking / Packaging / Marking)

In all rules, the seller must pay the costs of any checking operations which are necessary for delivering the goods, such as checking quality, and measuring, packaging, weighing, or counting the goods.

The seller must also package the goods at its own cost unless it is usual for this particular good to be sold unpackaged, such as in the case of bulk goods.

The seller must also take into account the transport of the goods and package them appropriately unless the parties have agreed in their contract that the goods be packaged or marked in a specific manner.

B8 (Checking / Packaging / Marking)

In all rules, there is no obligation from the buyer to the seller regarding packaging and marking. There can, in practice, however, be agreed exceptions, such as when the buyer provides the seller with labels, logos, or similar.

FCA A9 / B9: allocation of costs

A9 (Allocation of costs)

The seller must pay all costs until the goods have been delivered under A2, except any costs the buyer must pay as stated in B9.

The seller has to pay any costs involved in providing the usual proof that the goods have been delivered. As such, if the contract between the parties states that proof must be a bill of lading or an air waybill, then the carrier’s document fee is for the seller.

The seller pays any costs, export duties and taxes, where applicable, related to export clearance.

If the seller requests the buyer to provide information or documents to assist the seller in their export formalities, then the seller must pay the buyer for these costs.

B9 (Allocation of costs)

Under FCA, the buyer must pay the seller all costs relating to the goods from when they have been “delivered” (other than any costs payable by the seller).

If the buyer has requested the seller to provide assistance in obtaining information or documents needed for the buyer to effect carriage, import formalities, insurance and transport documents, then the buyer must reimburse the seller’s costs.

Where applicable, the buyer pays any duties, taxes and other costs for transit or import clearance.

Additionally, provided the seller has advised that the goods have been clearly identified as the goods under the contract, the buyer pays any additional costs incurred if the buyer fails to nominate who is to take the goods from the seller or if that nominated person fails to do so.

FCA A10 / B10: notices

A10 (Notices)

Even though the buyer must arrange to take delivery of the goods under FCA, the seller must still give the buyer sufficient notice that either 1) the goods have been delivered or 2) the carrier or other assigned person has failed to take delivery within the time agreed.

B10 (Notices)

The buyer must notify the seller of a number of things so that the seller can deliver and carry out any export formalities.

These include:

- The contact details and the location of the carrier or other assigned person to whom the seller is to deliver;

- the selected time, if any, in the agreed delivery period (such as when a container terminal is accepting cargo for a particular vessel or when an airline requires cargo for a specific flight);

- the mode of transport;

- any transport-related security requirements.

Free Carrier (FCA): advantages and disadvantages

The history of FCA

The first version of FCA appeared in Incoterms® 1980 to take into account container and roll-on-roll-off transport by sea as well as transport by air, road, and rail.

It absorbed the previous FOR/FOT (Free on Rail/Free on Truck, “truck” referring to a railway wagon, not a road transport vehicle) appearing in the 1953 version to take into account the development of the rail freight network in Europe post World War Two, and FOB Airport which had initially appeared in the 1976 version to cater for the then-new era of larger more powerful aircraft being able to carry cargo in addition to the passengers’ baggage.

For some strange reason, in the Incoterms® 1990 version, FCA’s delivery article was expanded to detail specific delivery procedures for rail transport, road transport (not mentioned in any previous versions), inland waterway, sea transport, air transport, unnamed transport (!), and multimodal transport.

Sensibly Incoterms® 2000 revised this again to allow the current two options of delivery: 1) loaded at the seller’s premises or 2) not unloaded elsewhere, typically at the carrier’s premises.

FCA advantages

While initially seeming similar to EXW, FCA is the more practical rule to use in domestic and international cross-border trades where the seller wants to minimise its effort and costs.

Under FCA, the seller must load the goods onto the buyer’s means of transport.

This means that in most cases, the buyer’s truck backs up to the seller’s loading dock, and the seller’s staff and equipment complete the loading. Depending on local rules and regulations, it would usually be the truck driver’s responsibility to ensure that the load is secured on the truck, but this occurs after the seller has loaded the goods.

FCA is available for both domestic and international transactions.

If the transaction is an international trade, then the seller will need to complete any export formalities required by the country’s authorities.

This usually means that the buyer must inform the seller of the means of transport from the seller’s country, whether by road, rail, air or sea.

The buyer will usually need to tell the seller:

- the name and contact details of its carrier,

- the freight booking information, including reference numbers and

- any relevant data such as:

- truck registration,

- railcar number,

- flight details, or

- vessel details.

This allows the seller to correctly declare the date of export and the means of export to its authorities. The seller can outsource this task to the buyer’s carrier if they agree, at the seller’s cost.

FCA disadvantages

If the buyer does not provide the seller with the carrier’s details or booking information, directly or through their carrier, the buyer loses any claims against the seller and is likely in breach of the contract.

A similar breach occurs if the buyer or their carrier fails to collect the goods at the agreed time and place.

In setting its selling price, the seller incorporates the estimated costs for loading the goods and completing export formalities, along with a buffer for unexpected expenses, administrative costs, and a profit margin. These costs, including the original EXW price, are not itemised for the buyer but are included in the overall FCA price.

The seller’s responsibility for the goods ends once they are “delivered”, whether at its premises or to a location specified by the buyer or their carrier.

This means if the goods are damaged or destroyed after leaving the seller’s premises, the seller is still entitled to payment, having fulfilled its delivery obligation. This is true even if the buyer’s truck were to spontaneously burst into flames at the seller’s loading dock moments after the loading has been completed.

In FCA transactions for exports, the seller typically does not need to charge VAT/GST, although evidence of export may be required by the seller’s tax authorities to validate this exemption.

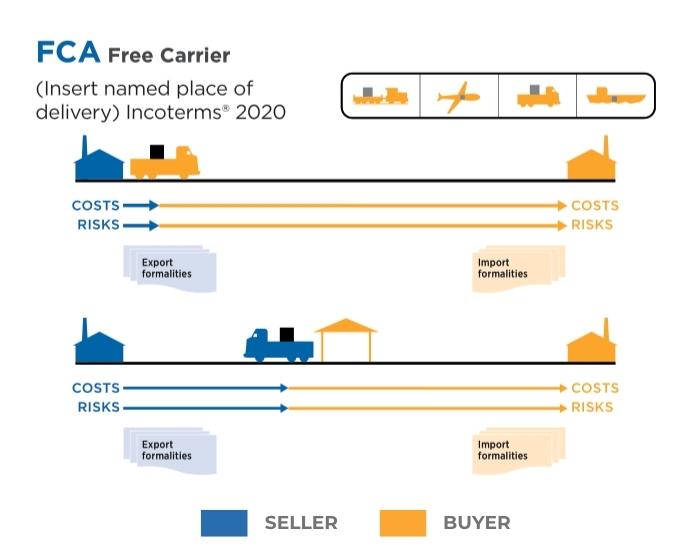

Free Carrier (FCA) Diagram 2024

Diagram: The FCA (Free Carrier) rule requires the seller to deliver the goods to the buyer or its carrier either 1) at the seller’s premises, loaded onto the collecting vehicle, or 2) delivered to another premises (typically a forwarder’s warehouse, airport or container terminal) not unloaded from the seller’s vehicle. Source: ICC

What does FCA mean?

FCA stands for “Free Carrier”, and it is one of the International Chamber of Commerce’s (ICC) international commercial terms (Incoterms).

FCA is most similar to the EXW Incoterm, although there are still differences between the two.

Is FCA the same as Ex Works?

FCA is not the same as Ex Works (EXW).

While they are similar, the FCA Incoterms rule places more responsibility on the seller in the transaction. Namely, the seller is generally also responsible for loading charges, delivery to the port, and export duties and taxes (although the exact terms of the contract can alter these even in a transaction using FCA Incoterms).

What is the difference between FCA and DAP?

DAP (delivered at place) is an Incoterms rule that sits at the opposite end of the buyer-seller responsibility spectrum.

Under FCA, the buyer will handle many of the aspects of the shipment, while under DAP, the seller will handle all except import duties and taxes.

What is the difference between FOB and FCA?

FOB (free on board) is an Incoterms rule where the seller is responsible for the shipment up until the point where the goods are loaded onto the vessel. Relative to FCA, this also adds origin terminal charges and loading on carriage responsibility to the seller’s docket.

Another difference is that FCA is an Incoterm rule that can be used for any mode of transport, while FOB is only for sea and inland waterway transport.

Can FCA be used for sea freight?

FCA is one of the Incoterms rules that can be used for any transport mode. This means that it can be used for sea freight as well as for various modes of land transport.

What does FCA mean in transport?

FCA is the short form for the Incoterm ‘Free Carrier’.

This is one of the Incoterms that can be used to help dictate responsibility in international commercial transport so all parties have a common understanding of who must do what. FCA can be used for any transport mode.

Free Carrier and letters of credit

For the first time, Incoterms® 2020 introduces the requirement that if the seller requests it, the buyer must instruct its carrier to issue the seller with a transport document stating that the goods have been loaded.

While this addition is mentioned in the explanatory notes for FCA as specifically regarding the issue of a bill of lading, in B6, it mentions “a transport document stating that the goods have been loaded (such as a bill of lading with an on board notation)”.

This does not preclude the seller and buyer from agreeing in their contract that a copy of either the bill of lading, air waybill marked “original for shipper”, or road or rail transport document can be provided to the seller for other purposes such as reporting the transaction as an export for taxation purposes.

The shipper in such a document should usually still be shown as the buyer, not the seller.

This is because the seller is not a party to the contract of carriage and does not want any of the liabilities of the shipper, but the document ideally will evidence in some way that the goods were sourced from the seller.

Risks and insurance in FCA transactions

What happens if the buyer refuses payment as a result of a dispute? What if the documents under an LC are not compliant and the market price has collapsed? What if the buyer becomes bankrupt during transit?

These are all matters that fall beyond the purview of the Incoterms® 2020 rules, but a prudent seller would investigate obtaining contingency insurance for the marine risks because the risk will still be theirs.

Advantages and disadvantages for the buyer

There are many advantages to the buyer of using FCA with an LC.

It allows the buyer control of the carriage of the goods, possibly consolidating them from multiple sales into economical transport units such as a full truckload or a full container load (FCL).

It also gives the buyer a degree of control over its transport costs by negotiating rates with its own carrier of choice, eliminating the need to pay the seller a markup on the seller’s freight costs. Under FCA, the buyer will also have complete transparency as to where its goods are at any time since it is using its own carrier.

Disadvantages to the buyer when using an LC under FCA include the risk of loss or damage to the goods, which commences at the earliest point in the seller’s country.

Another disadvantage is the need to pay inland costs in the seller’s country, but any good freight forwarder should be able to use its local office or agent in the seller’s country to advise on these accurately.

The advantages to a buyer may outweigh the disadvantages, but a prudent buyer should maintain an open marine insurance policy under the Institute Cargo Clauses (A) or (Air) with its warehouse-to-warehouse coverage.

Concerns and provisions for export evidence

Another concern for the buyer could be that without an on-board bill of lading, it would not have any evidence of the date of export.

This might be important if the buyer’s country converts the transaction’s value into local currency for value for duty using the exchange rate on the date of export.

Contractual details and payment by LC

One provision that has been in the Incoterms® rules ever since the 1990 version is that the seller must arrange for shipment at the buyer’s cost and risk on the “usual terms” if it is so agreed on in the contract.

Sellers, however, should be wary of doing this.

While this could be desirable depending on the mode of transport and customary procedures in the relevant countries, it may also have unfortunate legal consequences.

The contract should lay out very specifically what is required of the seller and limit their liability if they are to be declared as the shipper or consignor.

This provision seems a little at odds with how FCA is supposed to work and presumably was added when the rules were written for a Euro-centric trade world where the seller can truck goods at the buyer’s cost and risk.

Whether it has a place now in the broader world of cross-border international trade dependent on sea transport is a good question, but nevertheless, the prevailing thought was to leave it in the FCA rule as “it can’t hurt”.

Navigating LC requirements and practical considerations

If the buyer requires extra documents such as a certificate of origin, the seller must assist the buyer, at the buyer’s request, risk and cost, to obtain it.

If the parties want payment to be by LC, the banks will have problems again. While the FCA Incoterms® 2020 rule now provides for the seller to be given a transport document by the buyer’s carrier, if agreed in the contract, typically LCs include a latest shipment date.

It is not the seller’s responsibility to do anything beyond the delivery point, so for example, in a container shipment, the seller could deliver on the last day of the shipment period, meaning the container would not be loaded on board for several days, and sometimes in peak seasons or bad weather, possibly not for two or three weeks after that.

Using SWIFT messaging

The solution to this is to include in the contract that the LC must specify a place of receipt (SWIFT MT700 tag 44A) and a place of delivery (tag 44B). Typically, banks also like to show a port or airport of loading (tag 44E) and a discharge port or destination airport.

The contract should also specify these so that if the buyer arranges transport from or to other ports, then they will possibly be in breach of the contract.

The contract should drill down to the fine details, such as local port or airport names which are likely to appear on the transport document, such as “BMT” for Bangkok Modern Terminal instead of just “Bangkok” or “Jan Smuts Airport” instead of just “Johannesburg airport”, or broaden the scope with “any” such as “any port in Bangkok” or “any airport in Johannesburg.”

Further, since the seller has no control over when the container is loaded on board or the date of the flight, the LC should state a latest delivery date (tag 44C) or shipment period (tag 44D) with at least 21 days added to the agreed delivery date or last day of the agreed period to allow for delays outside the seller’s control or responsibility.

The shipper on an LC

It might be tempting for the carrier to name the seller as the shipper on the transport document, as mentioned above, but the seller should be aware that the LC rules (UCP600 article 14k) allow that the shipper or consignor on any document need not be the beneficiary (seller).

The shipper or consignor, in the case of a transport document under FCA, should be the buyer, which then introduces a further problem for a sea shipment if the LC requires the bill of lading to be consigned to order and blank endorsed.

Since the seller is not the shipper, it cannot endorse the bill of lading, so if the LC calls for a negotiable bill of lading, then there is no choice for the seller/beneficiary to be shown as shipper whether it wants to be shown as a merchant on the bill of lading or not.

The bottom line

An FCA transaction does not easily lend itself to payment by LC, though it is possible with intelligent thought by the seller and buyer and, most importantly, by the buyer’s issuing bank, who will find themselves well out of their comfort zone and outside of the typical attitude of “we’ve always done it this way.”

FCA Video – 3 pieces of advice for Incoterms® 2020 for freight forwarders, banks and traders?

“Incoterms” is a registered trademark of the International Chamber of Commerce.

Refer to ICC publication no. 723E for the text.

Publishing Partners

- Incoterms Resources

- All Incoterms Topics

- Podcasts

- Videos

- Conferences