Free Alongside Ship (FAS) Incoterms® 2020 Rule

Contents

Free Alongside Ship (FAS) – Incoterms® 2020 Rules [UPDATED 2025]

The FAS (Free Alongside Ship) is an Incoterms rule that has its roots in the days of sailing ships. It requires the seller to place the goods alongside the vessel nominated by the buyer.

Introduction to Free Alongside Ship (FAS)

FAS is rarely used these days but still might be appropriate in some cases. For instance, it is typically seen in shipments of heavy machinery that are brought to the wharf or barged up alongside the vessel to be loaded on board by the buyer or its vessel’s equipment.

The goods are not delivered until the vessel is available in the port of shipment for the goods to be next to it.

Under FAS, the seller assumes all risk until the goods are unloaded at the specified location at the named loading port. The risk is transferred to the buyer when the goods have been placed alongside the vessel nominated by the buyer at the loading point at the named port of shipment.

The seller must carry out export formalities, and the buyer must carry out import formalities. The buyer is also responsible for the contract of carriage to the importing country, having the goods loaded onto the ship, and having them transported to the final destination.

Since the buyer contracts for carriage, “the shipper” on the bill of lading should be the buyer, not the seller. The seller will most likely require at least a mate’s receipt or some other form of evidence of export, such as a copy of the bill of lading for their VAT/GST purposes.

Free Alongside Ship Incoterms 2020 Rule – key changes and updates

First published in the original Incoterms® 1936, FAS in common usage has its origins in the days of sailing ships.

This first version was silent about export formalities. In the 1953 rules, it was made clear that the seller had to render the buyer assistance in obtaining an export licence and authorisation to export the goods. This continued in the 1990 version, but in Incoterms® 2000 the responsibility for carrying out export formalities switched quite logically to the seller.

FAS, because of its origins, is only suitable where the seller can actually place the goods alongside the vessel, either on the quay (wharf) or on a barge brought to the vessel’s side. This means that it is most commonly used for the sale of bulk commodity cargo such as oil, grain, and ore or for heavy-lift cargo.

It should not be used for container shipments – whether FCL (full container load) or LCL (less than container load) – since with these, the seller typically delivers the goods to the carrier at an inland point such as a container yard (CY – for FCLs) or a container freight station (CFS – for LCL consolidations).

While the term “Free Alongside Ship” (FAS) implies that sellers may simply place their goods next to a ship, the practical process is more complex and security-focused. In practice, sellers hand over the goods to the port authority or the carrier’s agent, who then moves the goods to the ship’s berth at the dock where the specified vessel is, or is expected to be, moored. Different ports have their own set of procedures and fees for handling cargo, which can affect the costs for sellers.

Free Alongside Ship (FAS) podcast

Free Alongside Ship (FAS) seller and buyer obligations – rule by rule

FAS A1 / B1 general obligations

A1 (General Obligations)

In each of the eleven rules, the seller must provide the goods and their commercial invoice as required by the contract of sale and any other evidence of conformity, such as an analysis certificate that might be relevant and specified in the contract.

Each of the rules also provides that any document can be in paper or electronic form as agreed in the contract, or if the contract makes no mention of this, then the rules default to what is customary.

The rules do not explicitly define what “electronic form” is. This ambiguity means that it can be anything from a .pdf file to a blockchain record or another format yet to be developed.

B1 (General obligations)

In each of the rules, the buyer must pay the price for the goods as stated in the contract of sale.

The rules do not refer to when the payment is to be made (e.g., before shipment, immediately after shipment, thirty days after shipment, etc.) or how it is to be paid (e.g., prepayment, against an email of copy documents, on presentation of documents to a bank under a letter of credit, etc.).

These matters should be specified in the contract.

FAS A2 / B2: delivery

A2 (Delivery)

Under FAS, the seller “delivers” by placing the goods alongside the vessel nominated or provided by the buyer on the agreed date or within the agreed period as notified by the buyer, or, if there is no such time notified, then at the end of that period.

The way in which the goods are delivered will be dependent on the nature of the goods and the customs of the port.

For example, the goods might be, say, rolls of aluminium sheet, in which case they will likely have an outer sheath and strapping. They could be granite slabs strapped to pallets. They could be timber logs. They could be a large item of complex machinery or some other product. They could be sitting on the quay, or they could be barged downriver to the vessel. But

The critical point is that the vessel must be present to be alongside. Placing the goods on the quay, for example, before the vessel berths, is not delivery under FAS.

B2 (Delivery)

The buyer’s obligation is to take delivery when the goods have been delivered, as described in A2.

FAS A3 / B3: transfer of risk

A3 (Transfer of risk)

In all the rules, the seller bears all risks of loss or damage to the goods until they have been “delivered” in accordance with A2 described above.

The exception is loss or damage in circumstances described in B3 below, which varies depending on the buyer’s role in B2.

B3 (Transfer of risk)

The buyer bears all risks of loss or damage to the goods once the seller has delivered them as described in A2.

If the buyer fails to inform the seller of where and when the vessel will be presented, if the vessel fails to arrive on time, or if it fails to take the goods so that the seller cannot deliver, then the buyer bears the risk of loss or damage to the goods from the agreed date or at the end of the agreed period.

FAS A4 / B4: carriage

A4 (Carriage)

Under FAS, the seller has no obligation to contract for carriage.

If the buyer requests it, the seller (at the buyer’s risk and cost) must provide the buyer with any information known by the seller, including transport-related security requirements, that the buyer needs to arrange carriage.

If agreed, the seller must contract for carriage (at the buyer’s risk and cost) on the usual terms, which are usually agreed upon in the contract or determined by previous dealings between the parties.

The seller must comply with any transport-related security requirements but only up to delivery.

B4 (Carriage)

The buyer must contract for carriage, which includes the loading on board from the port of shipment, except if it is agreed that the seller makes the contract of carriage as described in A4.

FAS A5 / B5: insurance

A5 (Insurance)

The seller does not have the risk beyond the delivery point, so it has no obligation to the buyer to arrange a contract of insurance.

However, if the buyer requests (at its risk and cost), the seller must provide the buyer with information in its possession that the buyer needs to arrange its insurance.

B5 (Insurance)

Despite having the risk of loss or damage to the goods from the delivery point, the buyer does not have an obligation to the seller to insure the goods.

Whether the buyer chooses to insure the goods or bear the risk themselves is entirely their choice.

FAS A6 / B6: delivery / transport document

A6 (Delivery / Transport document)

Under FAS, the seller (at its own cost) must provide the buyer with the usual proof that the goods have been delivered in accordance with A2.

The specific form of this proof will likely be agreed on in the contract of sale and depend on factors like the nature of the goods and whether the goods are placed on the quay or brought to the vessel’s side by a barge.

Unless this proof is a transport document, then the seller must assist the buyer (at the buyer’s request, risk, and expense) to obtain a transport document.

B6 (Delivery / Transport document)

The buyer must accept the proof of delivery provided by the seller.

FAS A7 / B7: export / import clearance

A7 (Export/ Import clearance)

FAS, like all the multimodal rules, is suitable for both domestic and international transactions.

Under FAS, the seller must (at its own risk and expense) carry out all export clearance formalities required by the country of export, such as:

- licences or permits,

- security clearance for export,

- pre-shipment inspection, and

- any other authorisations or approvals.

The seller has no obligation to arrange any transit/import clearances.

However, if the buyer requests (at its own risk and cost), the seller must assist in obtaining any documents or information that relate to formalities required by the country of transit or import, such as:

- permits or licences,

- security clearance for transit/import,

- pre-shipment inspection required by the transit/import authorities, and

- any other official authorisations or approvals.

B7 (Export/ Import clearance)

Where applicable, the buyer must assist the seller (at the seller’s request, risk, and cost) in obtaining any documents or information needed for all export-related formalities required by the country of export.

Where applicable, the buyer must carry out and pay for all formalities required by any country of transit and the country of import. These include:

- licences and permits required for transit,

- import licences and permits required for import,

- import clearance,

- security clearance for transit and import,

- pre-shipment inspection, and

- any other official authorisations and approvals.

These are the buyer’s responsibility because they occur after “delivery” by the seller.

At first glance, it might seem strange that both seller and buyer are responsible for pre-shipment inspections. To clarify, the seller is responsible if it is a requirement of the country of export, and the buyer is responsible if it is a requirement of the country of transit/import.

FAS A8 / B8: checking / packaging / marking

A8 (Checking / Packaging / Marking)

In all rules, the seller must pay the costs of any checking operations which are necessary for delivering the goods, such as checking quality, and measuring, packaging, weighing, or counting the goods.

The seller must also package the goods (at its own cost) unless it is usual for this particular good to be sold unpackaged, such as in the case of bulk goods.

The seller must also take into account the transport of the goods and package them appropriately unless the parties have agreed in their contract that the goods be packaged or marked in a specific manner.

B8 (Checking / Packaging / Marking)

In all rules, there is no obligation from the buyer to the seller regarding packaging and marking. There can, in practice, however, be agreed exceptions, such as when the buyer provides the seller with labels, logos, or similar.

FAS A9 / B9: allocation of costs

A9 (Allocation of costs)

The seller must pay all costs until the goods have been delivered under A2 (meaning alongside the vessel for FAS) except any costs the buyer must pay as stated in B9.

Under FAS, the seller has to pay:

- any costs involved in providing the usual proof that the goods have been delivered, so if the contract between the parties states that proof is a bill of lading, then the seller pays any document fee,

- any costs, export duties and taxes, where applicable, related to export clearance.

Further, if the seller requests that the buyer provide any information or documents in relation to customs clearance, then the seller must pay the buyer for these costs.

B9 (Allocation of costs)

Under FAS, the buyer must pay:

- any duties, taxes and other costs for transit or import clearance, where applicable,

- all costs relating to the goods from when they have been “delivered” (meaning alongside the vessel under FAS), other than those payable by the seller

If the buyer has requested the seller to provide assistance in obtaining information or documents needed for the buyer to effect loading on board, carriage, import formalities, insurance, and transport documents, then the buyer must reimburse the seller’s costs.

Additionally, if the seller has advised that the goods have been clearly identified as the goods under the contract, the buyer pays any additional costs that arise from:

- the buyer failing to nominate the vessel,

- the vessel failing to take the goods from the seller, or

- the vessel closing for cargo earlier than when the buyer notified the seller.

FAS A10 / B10: notices

A10 (Notices)

The seller must give the buyer sufficient notice that the goods have been delivered alongside the buyer’s vessel or that the vessel failed to take delivery once they were made available. (This could occur, for example, when the vessel departed without loading the goods from the quay or the barge).

While FAS does not make the requirement anywhere, it would be logical to include in the seller’s notice any specific requirements the buyer’s vessel might need to make to take delivery of the goods and load them onto the vessel.

These matters would usually be specified in the sales contract between the two parties.

B10 (Notices)

The buyer must give sufficient notice to the seller of:

- any transport-related security requirements and

- the vessel’s name and loading point within the port of loading.

These would usually be specified in the contract.

Free Alongside Ship (FAS): advantages and disadvantages

Advantages and disadvantages for the seller

The FAS rule gives the seller the advantage of simply placing the goods alongside the vessel that is to take the goods.

The potential disadvantage to the seller is that it may have scheduled the goods to be put alongside on a particular date only to get there and find no vessel to be alongside.

Possibly, the vessel’s berthing was delayed due to congestion at the load port or possibly the vessel was delayed in transit by bad weather. Nevertheless, until the vessel is in a position for the goods to be truly considered “alongside”, the seller retains the risk of loss or damage to the goods.

Another disadvantage for the seller is that unless the parties agree that the seller will be given a transport document (typically the bill of lading), the seller has to assist the buyer in obtaining the transport document.

So if all the seller receives is a mate’s receipt, then the seller would have to tender that to have a bill of lading issued to the buyer. If the bill of lading is issued to the seller, the seller should ideally endeavour to check if it is entitled to be named as the consignor/shipper under the contract of carriage to avoid any unforeseen consequences.

Such a bill of lading would more correctly be a “received for shipment” bill of lading as there is no requirement for the seller to load the goods on board the vessel.

Advantages and disadvantages for the buyer

The advantage to the buyer is that it provides the vessel to load and is in control from that point on.

The buyer needs to ensure that the vessel has the means to load the goods from the quay or barge or that suitable lifting equipment is available on the quay or barge. Loading is at the buyer’s risk and cost.

If the buyer requires extra documents, such as a certificate of origin, the seller must assist the buyer in obtaining it (at the buyer’s request, risk, and cost).

There could be complications if the issuing authority in the seller’s country will only show a registered company in that country as the exporter/shipper/consignor since the seller is only the exporter but not the shipper or consignor.

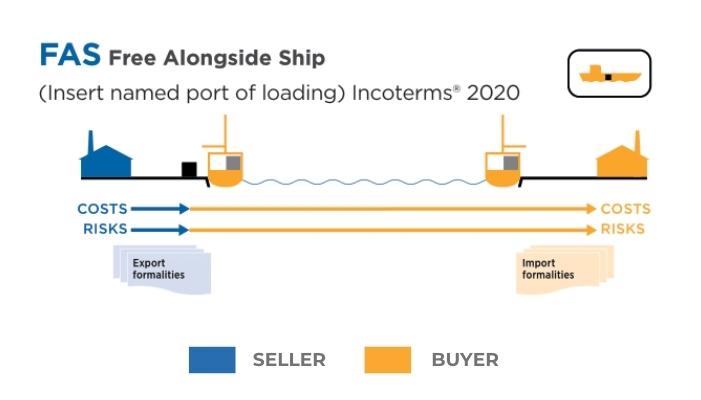

Free Alongside Ship (FAS) diagram 2024

Diagram: FAS – obligations from the seller and buyer, and where the transfer of risk between each party is transferred at the Point of Origin. Source: ICC

Free Alongside Ship and letters of credit

Using the Free Alongside Ship (FAS) incoterms rule with a letter of credit requires careful planning, especially regarding the receipt of a bill of lading marked “on board”. Without such a document, proving that the goods were indeed loaded onto the vessel – and thereby triggering the release of payment under the letter of credit – can be difficult.

Furthermore, given the possibility of a delay between when the goods are placed alongside the ship and when they are actually loaded, it is important to allow a margin on the latest shipment date within the terms of the letter of credit.

This ensures that the seller has sufficient time to load the goods onto the ship without breaching the terms of the credit, thus avoiding potential financial and logistical complications.

FAS Video – Why have the ICC created Incoterms® and why have they been updated in 2020?

“Incoterms” is a registered trademark of the International Chamber of Commerce.

Refer to ICC publication no. 723E for the text.

Publishing Partners

- Incoterms Resources

- All Incoterms Topics

- Podcasts

- Videos

- Conferences