Delivered Duty Paid (DDP) Incoterms® 2020 Rule

Contents

What is DDP?

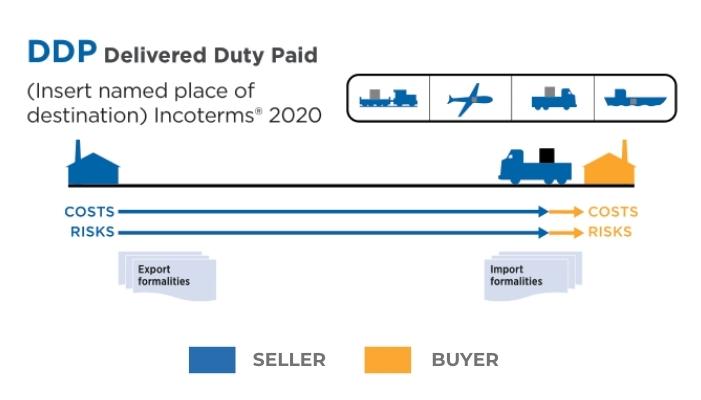

Delivered Duty Paid (DDP) is an Incoterms Rule where the seller is responsible for all costs associated with the delivery of goods to the named destination.

Under DDP, it is also the seller’s responsibility to pay both export and import duties, taxes, and fees.

Delivery Duty Paid Incoterms Rule

DDP should be used with great care as the seller might need to be a registered entity both for import and VAT/GST in the buyer’s country, which is a fairly unlikely scenario.

If the seller finds itself unable to be the importer or to be able to recover any VAT/GST paid then the parties should instead contract on DAP terms.

Delivery Duty Paid Incoterms 2020 Rule – key changes and updates

DDP stands for Delivery Duty Paid, an international commerce term (Incoterm) used to describe the delivery of goods where the seller takes most responsibility.

Under DDP, the supplier is responsible for paying for all of the costs associated with the delivery of goods right up until they get to the named place of destination. The buyer is then responsible for unloading the goods at the end destination.

DDP can be used to describe ocean, road, or air transportation of goods, including multimodal transportation. It’s also expected that the seller clears the goods at export and import customs.

Delivery Duty Paid (DDP) Incoterms 2020 Rules Guide

A 16-page guide on the Delivery Duty Paid (DDP) Incoterms® 2020 Rule, to be used in conjunction with The International Chamber of Commerce’s (ICC) new book, INCOTERMS® 2020

This short guide provides an article by article commentary on the Delivery Duty Paid Incoterms® Rule.

.

Delivery Duty Paid (DDP): advantages and disadvantages

This rule was originally published in Incoterms® 1967 and has continued largely unchanged in its intent.

The seller must deliver the goods as in DAP, but this time all import clearance formalities are at the cost and risk of the seller. This may well work fine with domestic transactions or transactions within a customs union, but for cross-ocean international trade, it can be particularly problematic.

As the opposite of EXW, where the buyer must be able to carry out the export clearance formalities, with DDP, the seller must be able to carry out the import clearance formalities.

The importing country’s rules might require an importer to be a registered commercial entity in that country, there might need to be an import permit being issued, and as the seller is highly unlikely to be a registered or recognised commercial entity in the importing country (not through another related entity that is itself registered there), there are likely to be all sorts of problems.

Add to these, if the importing country charges VAT/GST on imports (unless otherwise agreed in the contract and permitted by that tax regime), then the seller will pay these taxes and may not be able to recoup them.

Delivery Duty Paid (DDP) podcast

Delivery Duty Paid (DDP) seller and buyer obligations

A1 (General Obligations)

In each of the eleven rules, the seller must provide the goods and their commercial invoice as required by the contract of sale and any other evidence of conformity, such as an analysis certificate that might be relevant and specified in the contract.

Each of the rules also provides that any document can be in paper or electronic form as agreed in the contract, or if the contract makes no mention of this, then the rules default to what is customary.

The rules do not explicitly define what “electronic form” is. This ambiguity means that it can be anything from a .pdf file to a blockchain record or another format yet to be developed.

B1 (General obligations)

In each of the rules, the buyer must pay the price for the goods as stated in the contract of sale.

The rules do not refer to when the payment is to be made (e.g., before shipment, immediately after shipment, thirty days after shipment, etc.) or how it is to be paid (e.g., prepayment, against an email of copy documents, on presentation of documents to a bank under a letter of credit, etc.).

These matters should be specified in the contract.

DDP A2 / B2: delivery

A2 (Delivery)

The DAP and DDP rules require the seller to take on almost the maximum responsibility of placing the goods at the disposal of the buyer at the agreed destination place (or point within that place) but not unloaded from the arriving means of transport. This usually would be a truck but could be a train, barge, ship or even sometimes a chartered aircraft.

A common mistake with DAP and DDP is the belief that the destination will always be the buyer’s premises. This does not need not be the case, as the buyer could nominate anywhere it chooses. This could be the site of a new factory they are building for their client, it could be the container terminal in the destination country, or it could be somewhere else entirely.

If the chosen place is the buyer’s premises or a site they have nominated, then usually, they would have the equipment on hand to unload the goods. If they don’t, or if the goods require specialised equipment, then the Delivered at Place Unloaded (DPU) Incoterms would likely be preferable.

The delivery must be made on the agreed date or within the agreed period.

B2 (Delivery)

The buyer’s obligation is to take delivery when the goods have been “delivered”, as described in A2.

DDP A3 / B3: transfer of risk

A3 (Transfer of risk)

In all the rules, the seller bears all risks of loss or damage to the goods until they have been “delivered” in accordance with A2 described above.

The exception is loss or damage in circumstances described in B3 below, which varies depending on the buyer’s role in B2.

B3 (Transfer of risk)

The buyer bears all risks of loss or damage to the goods once the seller has “delivered” them as described in A2.

If the buyer fails to inform the seller exactly where they need to deliver the goods or fails to assist the seller with import formalities, then they bear the risk of loss or damage to the goods from the agreed date or agreed period for delivery.

The buyer’s obligation is in loss or damage in circumstances described in B3 below, which varies depending on the buyer’s role in B2.

DDP A4 / B4: carriage

A4 (Carriage)

Under DDP, the seller must arrange, or contract for, and bear the cost of carriage to the named place of destination. If there is an agreed point within that destination, then to that point.

As the seller has to arrange the carriage, it needs to know from the buyer if there is a specific point in the place of delivery to which the goods must be transported.

For example, if the destination is shown as simply “Budapest, Hungary”, where in that large metropolis is the seller’s carrier to leave the goods? It could be that it is to be the buyer’s premises or a particular location, say in an empty building site, the carrier’s premises, the airport, the container yard, or a particular quay on the river… the exact point should be agreed upon.

If the exact location is not specified, then the seller can select the point that best suits its purpose, which will usually be the cheapest option, such as a cargo terminal.

Under DDP, the seller must notify the buyer when the goods have been delivered to the carrier and their anticipated time of arrival.

B4 (Carriage)

The buyer has no obligation to the seller to arrange a contract of carriage, although, under DDP, they are responsible for unloading the goods at the named place of destination.

DDP A5 / B5: insurance

A5 (Insurance)

Despite the seller having the risk of loss or damage to the goods up to the delivery point, the seller is not required to provide any cargo insurance.

B5 (Insurance)

Because the seller has the risk of loss or damage to the goods up to the delivery point, the buyer does not have an obligation to the seller to insure the goods.

DDP A6 / B6: delivery / transport document

A6 (Delivery / Transport document)

Under DDP, the seller (at its own cost) must provide the buyer with any document the buyer needs to take over the goods.

The specific form of this documentation will depend on the agreement in the contract and could be as simple as a receipt that the buyer is to sign.

B6 (Delivery / Transport document)

Under DDP, the buyer is obligated to accept the documentation provided in A6, since it actually takes no part in the transport process.

DDP A7 / B7: export / import clearance

A7 (Export / Import clearance)

Under DDP, the seller must (at its own risk and expense) carry out:

- all export clearance formalities required by the country of export, (including: licences or permits; security clearance for export; and pre-shipment inspection),

- all import clearance formalities required by the country of import, and

- any other authorisations or approvals.

Additionally, as the point of delivery in these rules is in the importing country, the seller must also carry out and pay for any formalities required by any country of transit and the country of import.

B7 (Export / Import clearance)

Where applicable, the buyer must assist the seller (at the seller’s request, risk, and cost) in obtaining any documents or information the needed for all customs clearance formalities. This includes those required by the country of export, any country of transit, and the country of import.

DDP A8 / B8: checking / packaging / marking

A8 (Checking / Packaging / Marking)

In all rules, the seller must pay the costs of any checking operations which are necessary for delivering the goods, such as checking quality, and measuring, packaging, weighing, or counting the goods.

The seller must also package the goods (at its own cost) unless it is usual for this particular good to be sold unpackaged, such as in the case of bulk goods.

The seller must also take into account the transport of the goods and package them appropriately unless the parties have agreed in their contract that the goods be packaged or marked in a specific manner.

B8 (Checking / Packaging / Marking)

In all rules there is no obligation from the buyer to the seller as regards packaging and marking. There can, in practice, however, be agreed exceptions, such as when the buyer provides the seller with labels, logos, or similar.

DDP A9 / B9: allocation of costs

A9 (Allocation of costs)

The only difference between DAP and DDP is that the seller must pay for all costs until the goods have been delivered up to the time they have been delivered, including all import formalities. This may well include VAT/GST.

Under DDP, the seller must pay:

- costs of transportation,

- export and import requirements, fees, duties, tariffs and taxes,

- any customs charges for transport through other countries,

- the cost of providing the buyer with proof that the goods have been delivered, and

- if applicable, VAT/GST.

Further, if the seller requests that the buyer provide any information or documents in relation to customs clearance, then the seller must pay the buyer for these costs.

B9 (Allocation of costs)

Under DDP, the buyer must pay:

- the costs of unloading the goods at the named place of destination,

- all costs relating to the goods from when they have been delivered (other than those that are payable by the seller).

Additionally, if the seller has advised that the goods have been clearly identified as the goods under the contract, the buyer must pay any additional costs that arise from the buyer failing to give notice in accordance with B10.

DDP A10 / B10: notices

A10 (Notices)

The seller must give the buyer any notice the buyer needs to receive the goods.

B10 (Notices)

If the parties agree in the contract, the buyer must give the seller sufficient notice of when and the point within the place of destination where they require delivery.

The contract will usually detail how much notice the buyer must give, as this is likely to vary with the modes of transport used.

Delivery Duty Paid (DDP) diagram 2024

Delivery Duty Paid (DDP) and letters of credit

There are some issues that arise when using DDP with letters of credit (LC) depending on the way the importing country determines their local currency equivalent to calculate the value for duty.

If it uses the date of export, what document will the seller have as evidence of this by way of an onboard notation? Will it be able to produce a bill of lading or sea waybill consigned to itself evidencing this?

Some customs regimes are now considering that the buyer from the DDP seller is liable for any shortfall of duty and any fines, even though they were not involved or named in the import clearance formalities. This is because, for the customs authority, it is far easier to penalise a domestic business than to chase a foreign seller.

Again, in hindsight, DDP probably does not go far enough. EXW requires the buyer to load the vehicle at the point of delivery, yet DDP does not require the seller to unload at the delivery point.

The same comments regarding LCs in DAP and DPU apply to DDP.

Letters of Credit under DAP, DPU, and DDP

DAP, DPU, and DDP transactions are largely incompatible with payment by the typical LC.

With delivery only occurring at the very end of the transport chain, an LC calling for the presentation of, say, a bill of lading consigned to order and blank endorsed would be a contradiction to these three “D” Incoterms rules.

The situation becomes even more complex if the issuing bank routinely demands bills of lading to be consigned to its order, which is then endorsed over to the applicant (the buyer) to enable the buyer to take possession of the goods.

In such cases, the seller’s security is at risk if the buyer fails to take delivery of the goods. This risk is heightened by the fact that the seller’s truck may be left waiting at the buyer’s specified delivery location for unloading, all the while depending on the issuing bank to fulfil its obligations under the LC before the transfer of goods can be completed.

Imagine how strange it would be for the seller to arrive at the buyer’s receiving dock, obtain some form of delivery receipt from the buyer, send it back to their office overseas, and present it to their bank, which sends it to the issuing bank who hopefully honours the presentation.

Meanwhile, the truck is sitting blocking the receiving dock for a couple of weeks, with the driver having set up camp in the truck’s cabin until his office back home tells him they have received payment and he can now let the buyer unload!

DDP Video – Three pieces of advice for Incoterms® 2020 for freight forwarders, banks, and traders?

Delivered Duty Unpaid (DDU) – Incoterm explained

Delivered Duty Unpaid (DDU) was a widely used Incoterm under the ICC’s Incoterms 2000 rules. It required the seller to deliver goods to a named destination in the buyer’s country, covering all costs and risks except for import duties, taxes, and customs clearance. While DDU has been replaced by DAP (Delivered at Place) in the latest Incoterms 2010 and 2020 editions, it is still referenced in contracts and negotiations.

This guide outlines the responsibilities, risks, and structure of the DDU term, compares it with its successor (DAP), and discusses its relevance in international trade today.

Definition of DDU

Under DDU, the seller is responsible for:

• Export packaging

• Export duties and taxes

• Origin terminal handling charges (THC)

• Main carriage/freight

• Destination terminal handling charges

• Delivery to the named place in the destination country

The buyer is responsible for:

• Import duties and taxes

• Customs clearance in the destination country

Key responsibilities

Seller

• Arrange and pay for transport to the agreed point in the buyer’s country

• Bear all risk until delivery at destination

• Provide commercial invoice, packing list, and other shipping documents

• Assist with documentation required for import clearance (if requested)

Buyer

• Handle import clearance at destination

• Pay all import duties, VAT, and other taxes

• Bear any risk and cost after the named place of delivery

Risk transfer

The risk transfers from seller to buyer when the goods are delivered to the named place in the country of importation. Until then, all risks remain with the seller, even across international transport and delivery networks.

DDU vs DAP

In Incoterms 2010, DDU was replaced by DAP. The primary difference is structural clarity:

| Feature | DDU | DAP |

|---|---|---|

| Import duties | Buyer | Buyer |

| Risk transfer | At named destination place | At named destination place |

| Formal status | Discontinued (Incoterms 2000) | Official (Incoterms 2010/2020) |

| Use in contracts | Still common in legacy deals | Preferred in new contracts |

Practical application

DDU is often used in cases where:

• The seller wants to control logistics to the final destination

• The buyer has specific customs knowledge or arrangements for import

• Legacy trade contracts or ERP systems continue to support the term

Examples:

• A textile manufacturer in Turkey sells DDU to a retailer in the UK, arranging transport to the UK warehouse, but leaving the buyer to pay VAT and customs duty.

• A machinery supplier in Germany delivers DDU to a construction site in Brazil, covering all costs except Brazilian import taxes.

Advantages of DDU

• Greater control for the seller over delivery chain

• Clear cost separation between physical transport and customs responsibilities

• Attractive for buyers with local import clearance experience

Disadvantages and cautions

• Confusion due to its outdated status under Incoterms 2010 and 2020

• Potential delays if customs clearance is not coordinated

• Increased seller responsibility for all transport-related risks

• Possible disputes over exact delivery point and customs documentation

Recommendations for traders

• When negotiating contracts, use DAP instead of DDU to align with current Incoterms

• If DDU is referenced, clearly define the responsibilities and delivery location in the contract

• Ensure coordination between seller and buyer on customs clearance procedures to avoid delays

Legal and documentation considerations

• Always specify the named destination location clearly (e.g., “DDU – 123 Example Street, City, Country”)

• Use consistent documentation to support delivery terms, including commercial invoice and bill of lading

• Be aware that some freight forwarders may still use DDU terminology in practice

Conclusion

While DDU is no longer an official Incoterm, its practical relevance persists in many sectors and legacy systems. Traders should be cautious when using DDU, ensuring that responsibilities are clearly stated and both parties understand the implications. For clarity and compliance with current ICC standards, DAP is now the recommended alternative.

For full Incoterms guidance, refer to:

• Incoterms guidance from the UK government

• Trade Finance Global’s Incoterms hub

“Incoterms” is a registered trademark of the International Chamber of Commerce.

Refer to ICC publication no. 723E for the text.

Publishing Partners

- Incoterms Resources

- All Incoterms Topics

- Podcasts

- Videos

- Conferences