Delivered at Place (DAP) Incoterms® 2020 Rule

Contents

Delivered at Place (DAP) – Incoterms® 2020 Rules [UPDATED 2025]

Delivered at Place (DAP) is an Incoterms 2020 rule that can be used for any mode of transport.

It is sometimes considered to be an extension of Delivered at Place Unloaded (DPU), since the seller delivers the goods at a named destination, although under the DAP the buyer is responsible for unloading the goods.

Introduction to Delivered at Place (DAP)

Under the DAP Incoterm, the seller is responsible for:

- delivering the goods to a place named by a buyer (which is typically the buyer’s premises), and

- carrying out any export formalities.

The buyer is responsible for:

- arranging for goods to be unloaded at the named place of destination, and

- carrying out any import formalities.

Like with CPT and CIP, the seller contracts for carriage and risk transfers to the buyer only upon “delivery” (which now is at the buyer’s premises). Under DAP, the seller has no obligation to the buyer to insure for its risk.

This rule works well for the transport of goods by land within the European and Central Asian landmass but runs into potential problems once there is a change in the mode of transport along the way.

Delivered at Place Incoterms 2020 rule – key changes and updates

For example, if the shipment is by air and requires import clearance formalities in the destination country, these must be carried out by the buyer while the goods sit at the airport. Once cleared, the seller’s carrier (typically a freight forwarder) must then be given whatever paperwork they require to move the cargo from the airport to its final destination.

The same situation exists for cross-ocean container shipments with the added complication that the seller must return the empty container at its own expense.

It should be noted, as well, that the buyer should not be the consignee on any air waybill or bill of lading. That should be the seller since it is the seller who has to arrange for its forwarder to take possession of the goods from the airline or shipping company and arrange local inland transport, typically by truck.

If the goods are damaged or lost at any stage before the final destination, then the seller will be unable to deliver and may well be in breach of contract, with the additional complication that the buyer will have already paid import duties and VAT/GST.

If the buyer is unable to import clear the goods expeditiously, then it might find that it bears the risk while the goods sit in customs control and is itself in breach of contract if the seller cannot deliver the goods as contracted.

Delivered at Place podcast

Delivered at Place seller and buyer obligations

DAP A1 / B1 general obligations

A1 (General Obligations)

In each of the eleven rules, the seller must provide the goods and their commercial invoice as required by the contract of sale and any other evidence of conformity, such as an analysis certificate that might be relevant and specified in the contract.

Each of the rules also provides that any document can be in paper or electronic form as agreed in the contract, or if the contract makes no mention of this, then the rules default to what is customary.

The rules do not explicitly define what “electronic form” is. This ambiguity means that it can be anything from a .pdf file to a blockchain record or another format yet to be developed.

B1 (General obligations)

In each of the rules, the buyer must pay the price for the goods as stated in the contract of sale.

The rules do not refer to when the payment is to be made (e.g., before shipment, immediately after shipment, thirty days after shipment, etc.) or how it is to be paid (e.g., prepayment, against an email of copy documents, on presentation of documents to a bank under a letter of credit, etc.).

These matters should be specified in the contract.

DAP A2 / B2: delivery

A2 (Delivery)

The DAP and DDP rules require the seller to take on almost the maximum responsibility of placing the goods at the disposal of the buyer at the agreed destination place (or point within that place), but DAP does not require the goods to be unloaded from the arriving means of transport. This usually would be a truck but could be a train, barge, ship or even sometimes a chartered aircraft.

A common mistake with DAP and DDP is the belief that the destination will always be the buyer’s premises. This does not need not be the case, as the buyer could nominate anywhere it chooses. This could be the site of a new factory they are building for their client, it could be the container terminal in the destination country, or it could be somewhere else entirely.

If the chosen place is the buyer’s premises or a site they have nominated, then usually, they would have the equipment on hand to unload the goods. If they don’t, or if the goods require specialised equipment, then the Delivered at Place Unloaded (DPU) Incoterms would likely be preferable.

The delivery must be made on the agreed date or within the agreed period.

B2 (Delivery)

The buyer’s obligation is to take delivery when the goods have been “delivered”, as described in A2.

DAP A3 / B3: transfer of risk

A3 (Transfer of risk)

In all the rules, the seller bears all risks of loss or damage to the goods until they have been “delivered” in accordance with A2 described above.

The exception is loss or damage in circumstances described in B3 below, which varies depending on the buyer’s role in B2.

B3 (Transfer of risk)

The buyer bears all risks of loss or damage to the goods once the seller has “delivered” them as described in A2.

If the buyer fails to inform the seller exactly where they need to deliver the goods, or if the buyer fails to import-clear the goods, then they bear the risk of loss or damage to the goods from the agreed date or agreed period for delivery.

For example, if the seller despatches the goods to the buyer and they are held indefinitely by the importing country’s authorities because the buyer failed to obtain the necessary import permit, then it is the buyer who bears the risk.

DAP A4 / B4: carriage

A4 (Carriage)

Under DAP, the seller must arrange, or contract for, and bear the cost of carriage to the named place of destination. If there is an agreed point within that destination, then to that point.

As the seller has to arrange the carriage, it needs to know from the buyer if there is a specific point in the place of delivery to which the goods must be transported.

For example, if the destination is shown as simply “Budapest, Hungary”, where in that large metropolis is the seller’s carrier to leave the goods? It could be that it is to be the buyer’s premises or a particular location, say in an empty building site, the carrier’s premises, the airport, the container yard, or a particular quay on the river… the exact point should be agreed upon.

If the exact location is not specified, then the seller can select the point that best suits its purpose, which will usually be the cheapest option, such as a cargo terminal.

For both DAP and DPU, if the delivery at the destination is to occur after the buyer completes any necessary import formalities, then the buyer must bear the cost of storage due to delays in those formalities being completed (assuming the seller has provided the buyer with necessary documents in time).

The seller must bear the cost of any storage due to delays in import clearance.

B4 (Carriage)

Under DAP, the buyer has no obligation to the seller to arrange a contract of carriage.

DAP A5 / B5: insurance

A5 (Insurance)

Despite the seller having the risk of loss or damage to the goods up to the delivery point, the seller does not have an obligation to the buyer to insure the goods.

B5 (Insurance)

Because the seller has the risk of loss or damage to the goods up to the delivery point, the buyer does not have an obligation to the seller to insure the goods.

DAP A6 / B6: delivery / transport document

A6 (Delivery / Transport document)

The seller (at its own cost) must provide the buyer with any document the buyer needs to take possession of the goods.

The specific form of this documentation will depend on the agreement in the contract and could be as simple as a receipt that the buyer is to sign. With DAP, it may be the case that the buyer must import-clear the goods, so a copy of the seller’s transport document might be needed as evidence of the export and the date of shipment.

B6 (Delivery / Transport document)

Under DAP, the buyer is obligated to accept the documentation provided in A6, since it actually takes no part in the transport process.

DAP A7 / B7: export / import clearance

A7 (Export / Import clearance)

Where applicable, the seller must (at its own risk and cost) carry out all export clearance formalities required by the country of export, such as licences or permits, security clearance for export, or pre-shipment inspection.

Additionally, as the point of delivery under DAP is in the importing country, the seller must also carry out and pay for any formalities required by any country of transit before that delivery occurs.

The seller has no obligation to arrange any import clearances.

However, if the buyer requests it (at its own risk and cost), the seller must assist in obtaining any documents or information which relate to formalities required by the country of import, such as permits or licences, security clearance, or pre-shipment inspection required by the authorities.

B7 (Export / Import clearance)

When using DAP, the buyer must assist the seller (at the seller’s request, risk, and cost) in obtaining any documents or information needed for all export-related formalities required by the country of export and any country of transit.

Where applicable, the buyer must carry out and pay for all formalities required by the country of import.

These include:

- licences and permits required for import,

- import clearance,

- security clearance for import,

- pre-shipment inspection, and

- any other official authorisations and approvals.

DAP A8 / B8: checking / packaging / marking

A8 (Checking / Packaging / Marking)

In all rules, the seller must pay the costs of any checking operations which are necessary for delivering the goods, such as checking quality, and measuring, packaging, weighing, or counting the goods.

The seller must also package the goods (at its own cost) unless it is usual for this particular good to be sold unpackaged, such as in the case of bulk goods.

The seller must also take into account the transport of the goods and package them appropriately unless the parties have agreed in their contract that the goods be packaged or marked in a specific manner.

B8 (Checking / Packaging / Marking)

In all rules there is no obligation from the buyer to the seller as regards packaging and marking. There can, in practice, however, be agreed exceptions, such as when the buyer provides the seller with labels, logos, or similar.

DAP A9 / B9: allocation of costs

A9 (Allocation of costs)

The seller must pay all costs until the goods have been delivered under A2, except any costs the buyer must pay as stated in B9.

This means that under DAP, the seller must pay:

- any transport costs resulting from the contract of carriage, including costs of loading the goods and any transport-related security,

- the cost of providing the buyer with proof that the goods have been delivered,

- any costs, export duties, and taxes (where applicable) related to export clearance and any transit clearance

Further, if the seller requests that the buyer provide any information or documents in relation to export clearance, then the seller must pay the buyer for these costs.

B9 (Allocation of costs)

Under DAP, the buyer must pay:

- unloading costs (unless the seller paid them under the contract of carriage),

- any duties, taxes, and other costs for import clearance, where applicable, and

- all costs relating to the goods from when they have been delivered (other than those that are payable by the seller).

Further, if the buyer requests the seller to assist in obtaining information or documents needed for the buyer to effect import formalities, then the buyer must reimburse the seller’s costs.

Additionally, if the seller has advised that the goods have been clearly identified as the goods under the contract, the buyer must pay any additional costs that arise from the buyer failing to give notice in accordance with B10.

DAP A9 / B9: allocation of costs

A10 (Notices)

The seller must give the buyer any notice the buyer needs to receive the goods.

B10 (Notices)

If the parties agree in the contract, the buyer must give the seller sufficient notice of when and the point within the place of destination where they require delivery.

The contract will usually detail how much notice the buyer must give, as this is likely to vary with the modes of transport used.

Delivered at Place (DAP): advantages and disadvantages

The history of DAP

DAP is the new name given in the Incoterms® 2010 rules for the previous DDU (Delivered Duty Unpaid), which first appeared in the 1990 rules.

DDU was a misleading name because transactions under all rules (with the exception of DDP (Delivered Duty Paid)) were duty unpaid at the time of delivery. DDU itself actually meant that delivery occurred after the buyer had import cleared the goods and paid the duty, prompting the change to its current version.

Also rolled into DAP was the old DAF (Delivered at Frontier, first appearing in Incoterms® 1967) and DES (Delivered Ex Ship, originally “EXS” Ex Ship in the 1953 rules) which like DDU, provided for delivery not unloaded.

These two were effectively redundant as by stating “at the named place of destination” in DDU it included at the frontier or on the ship.

Advantages

The DAP Incoterms® 2020 rule does not specify that the place of delivery must be the buyer’s premises even though that is common usage.

Under DAP, the goods are considered to be “delivery” when the seller places “them at the disposal of the buyer on the arriving means of transport ready for unloading at the agreed point, if any, at the named place of destination.”

This means that the seller and buyer need to agree on precisely where that delivery is to take place. Without such agreement, how can the seller know where to deliver?

This rule is suitable for domestic trade as well as transactions within a customs union, however it can become impractical or problematic for cross-ocean trade.

Disadvantage

In cross-ocean transactions, the buyer must import-clear the goods, so typically, they will be held in a customs bonded warehouse or terminal until those formalities have been completed.

Until they go into customs control in the importing country, they are at the seller’s risk, but while they are under customs control, they are at the buyer’s risk. If the buyer has a problem, say with an incorrectly issued import permit, which delays clearance or even leads to a refusal to clear, the buyer’s actions prevent the seller from delivering.

Once import clearance has been completed, and assuming the delivery point was not the customs warehouse or terminal where the goods were waiting for that clearance, the goods need to be released to the seller’s carrier or its agent to then continue the journey to the named destination.

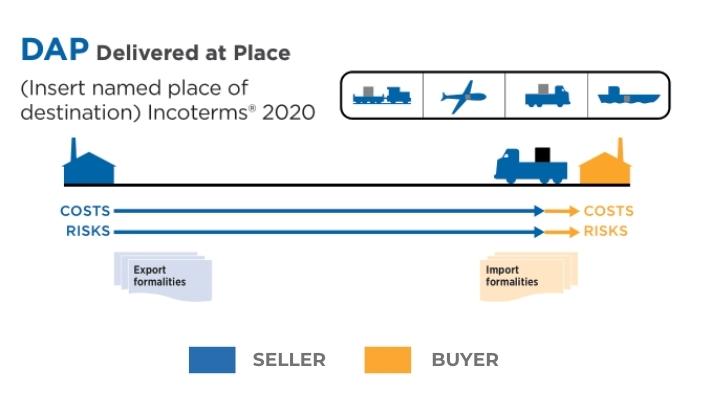

Delivered at Place (DAP) Diagram 2024

Diagram: DAP – obligations from the seller and buyer, and where the transfer of risk between each party is transferred. Source: ICC

Apart from when the goods are held waiting for import clearance, the seller has the risk of loss or damage to the goods.

The seller has no obligation to the buyer to provide insurance and the buyer has no insurable risk in the goods until delivered at the named place. The seller, of course, would be prudent to insure the goods, but it can choose to self-insure, meaning take the risk itself.

The seller needs to be very careful pricing a DAP sale, taking into account all possibilities and potential problems especially as part of transport may take place within the buyer’s country after release from the customs-controlled warehouse or terminal.

If the buyer requires extra documents, such as a certificate of origin, the seller must assist the buyer in obtaining it (at the buyer’s risk and cost).

Unlike all the preceding rules, the DAP seller is also responsible for any formalities which might occur in any country of transit, particularly important if the sale is to a final destination in a land-locked country and the sea shipment initially goes to a port in an adjacent country.

The seller is not required to give the buyer any transport document, but where the shipment is containerised by sea, the import authorities might require a transport document showing the date of export to calculate the value for duty in their local currency. This will be dependent on how that importing country values goods for import.

Is DAP better than CIP?

What advantages are there to the seller over CIP? Probably none.

The disadvantage to the seller is that the goods are at risk until the destination, except during any import clearance. If the goods are lost in transit, then the seller, assuming they cannot replace the goods before the contracted delivery date, would be in breach of their contract.

If the goods are damaged in transit, the seller would likewise be in breach of contract if they cannot make good that damage (at their cost and risk) within the contracted delivery period.

The contract might have hidden in it a rather onerous liquidated damages clause, the kind of thing about which many people’s eyes glaze over, and they disregard at their peril.

Delivered at Place and letters of credit

DAP transactions are largely incompatible with payment by the typical letter of credit (LC).

With delivery only occurring at the very end of the transport chain, an LC calling for the presentation of, say, a bill of lading consigned to order and blank endorsed would be a contradiction to DAP.

The situation becomes even more complex if the issuing bank routinely demands bills of lading to be consigned to its order, which is then endorsed over to the applicant (the buyer) to enable the buyer to take possession of the goods.

In such cases, the seller’s security is at risk if the buyer fails to take delivery of the goods. This risk is heightened by the fact that the seller’s truck may be left waiting at the buyer’s specified delivery location for unloading, all the while depending on the issuing bank to fulfil its obligations under the LC before the transfer of goods can be completed.

Imagine how strange it would be for the seller to arrive at the buyer’s receiving dock, obtain some form of delivery receipt from the buyer, send it back to their office overseas, and present it to their bank, which sends it to the issuing bank who hopefully honours the presentation.

Meanwhile, the truck is sitting blocking the receiving dock for a couple of weeks, with the driver having set up camp in the truck’s cabin until his office back home tells him they have received payment and he can now let the buyer unload!

DAP Video – What are Incoterms® 2020 and why are they important?

“Incoterms” is a registered trademark of the International Chamber of Commerce.

Refer to ICC publication no. 723E for the text.

Publishing Partners

- Incoterms Resources

- All Incoterms Topics

- Podcasts

- Videos

- Conferences