Cost and Freight (CFR) Incoterms® 2020 Rule

Contents

Cost and Freight (CFR) is one of the most commonly used trade terms after Free On Board (FOB), although in practice, it is used without reference to any version of the Incoterms® rules.

In such cases, it is up to the seller and buyer to agree in their contract on what they mean when they use these three letters.

Introduction to Cost and Freight (CFR)

In the Incoterms® 2020 rules, as in previous versions, Cost and Freight (CFR) requires the seller to place the goods on board the vessel contracted by themselves.

From that point on risk of loss or damage to the goods transfers to the buyer. “On board” is no longer defined as placing the goods “across the ship’s rail” and, in fact, is not defined any further as it will be a matter for the contract to specify depending on the nature of the goods.

The seller is responsible for packaging the goods for transport, clearing the goods for export, arranging for transport to the named port of destination, and loading the goods at the port of shipment. The bill of lading usually indicates “freight prepaid.”

The buyer is responsible for the costs of unloading the goods at the port of destination, the duties, tariffs, and taxes for import customs and any additional transportation costs to the final destination.

Like FOB, CFR has its origins in the sailing ship days.

CFR was abbreviated as “C&F” until Incoterms® 1990, when it was changed to CFR. In the days of telexes in the 1970s and 1980s, traders found that the ampersand sign “&” was not an international symbol in their telex messages, so common usage then became “CNF” as the phonetic version of C&F.

SWIFT also had problems with the ampersand in letters of credit, and quite possibly early computer programmers did too – imagine every rule being all alphabetical characters except one which has its middle character as an alphanumeric symbol but could sometimes be just an alphabetical character, better to make them all uniform.

Cost and Freight Incoterms 2020 rule – key changes and updates

It is important to understand that in CFR there are two ports concerned.

The seller delivers at the port of loading but pays freight to the port of destination, where the buyer is obligated to receive the goods from the carrier. The risk transfers to the buyer when the goods are on the vessel at the port of shipment, whereas the seller carries the cost of carriage to the port of destination. At the destination port, the buyer assumes the handling and customs costs.

Given that the word “carrier” does not appear elsewhere in this rule, it might have been better worded as receiving the goods from the vessel.

The seller and buyer should agree in their contract on who should pay for unloading: the seller in the contract of carriage or the buyer.

Under the Incoterms® 2020 rules, CFR is not appropriate for container shipments because the cargo is given to the carrier at a place some distance from the port, such as a container yard or even the seller’s premises.

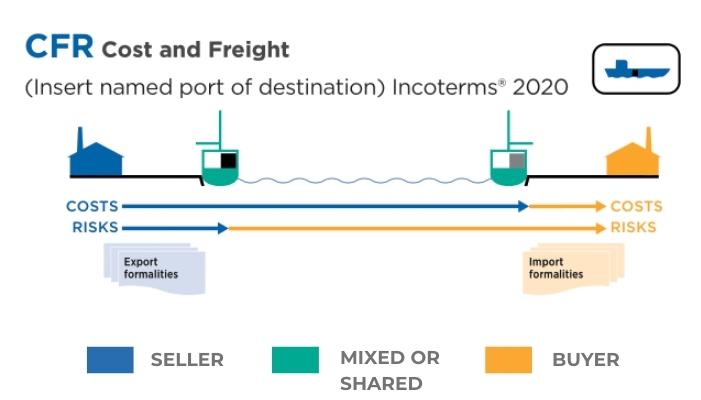

Cost and Freight (CFR) diagram 2024

Diagram: CFR – Cost and Freight requires the seller to place the goods on board the vessel contracted by themselves. From that point on risk of loss or damage to the goods transfers to the buyer. Source: ICC

Cost and Freight (CFR) podcast

CFR seller and buyer obligations – rule by rule

CFR A1 / B1 general obligations

A1 (General Obligations)

In each of the eleven rules, the seller must provide the goods and their commercial invoice as required by the contract of sale and any other evidence of conformity, such as an analysis certificate that might be relevant and specified in the contract.

Each of the rules also provides that any document can be in paper or electronic form as agreed in the contract, or if the contract makes no mention of this, then the rules default to what is customary.

The rules do not explicitly define what “electronic form” is. This ambiguity means that it can be anything from a .pdf file to a blockchain record or another format yet to be developed.

B1 (General obligations)

In each of the rules, the buyer must pay the price for the goods as stated in the contract of sale.

The rules do not refer to when the payment is to be made (e.g., before shipment, immediately after shipment, thirty days after shipment, etc.) or how it is to be paid (e.g., prepayment, against an email of copy documents, on presentation of documents to a bank under a letter of credit, etc.).

These matters should be specified in the contract.

CFR A2 / B2: delivery

A2 (Delivery)

Under CFR, the seller “delivers” by placing the goods on board the vessel on the agreed date or within the agreed period (if there is no such time notified then at the end of that period) and in the manner customary at the port.

Most importantly, delivery occurs when the seller loads the goods onto the vessel, not when the vessel reaches the destination port.

B2 (Delivery)

Under CFR, the buyer must:

- take delivery of the goods when the seller has delivered them on board the vessel and

- receive them from the carrier at the named destination port.

Most importantly, delivery occurs when the goods are released from the seller’s direct control, not when the goods reach the destination.

The main difference in wording to FOB is simply that with CFR and CIF, reference to the vessel being nominated by the buyer is absent, as is a reference to the buyer nominating a loading point within the load port.

The contract for carriage and cost implications are dealt with in other articles.

CFR A3 / B3: transfer of risk

A3 (Transfer of risk)

In all the rules, the seller bears all risks of loss or damage to the goods until they have been “delivered” in accordance with A2 described above.

The exception is loss or damage in circumstances described in B3 below, which varies depending on the buyer’s role in B2.

B3 (Transfer of risk)

The buyer bears all risks of loss or damage to the goods once the seller has delivered them as described in A2.

If the buyer fails to inform the seller about the destination port (or the point within that destination port), then the seller will be unable to deliver under A2, and the buyer bears the risk of loss or damage to the goods from the agreed date or at the end of the agreed period.

CFR A4 / B4: carriage

A4 (Carriage)

Under CFR, the seller must arrange (or procure in the case of a string-sale) a contract for the carriage of the goods from the agreed point of delivery in A2 to the named port of destination or, if agreed, to any point (quay or wharf) in that port.

The contract of carriage must be made on usual terms that are appropriate to the type of goods and by a vessel normally used for transporting the type of goods by the usual route (often agreed on in the contract of sale) at the seller’s cost.

B4 (Carriage)

The buyer has no obligation to the seller to arrange a contract of carriage.

CFR A5 / B5: insurance

A5 (Insurance)

The seller does not have the risk beyond the delivery point, so it has no obligation to the buyer to arrange a contract of insurance.

However, if the buyer requests (at its risk and cost), the seller must provide the buyer with information in its possession that the buyer needs to arrange its insurance.

B5 (Insurance)

Despite having the risk of loss or damage to the goods from the delivery point, the buyer does not have an obligation to the seller to insure the goods.

Whether the buyer chooses to insure the goods or bear the risk themselves is entirely their choice.

CFR A6 / B6: delivery / transport document

A6 (Delivery / Transport document)

Under CFR, the seller (at its own cost) must provide the buyer with the usual transport document covering transport to the agreed port of destination.

The transport document must cover the contracted goods within the agreed period for shipment.

If it is agreed, then this document must enable the buyer to claim the goods from the carrier at the named place of destination (and in a string sale, enable the buyer to sell the goods in transit to a subsequent buyer by transferring that document).

B6 (Delivery / Transport document)

The buyer must accept the transport document provided by the seller if it conforms with the contract between them.

CFR A7 / B7: export / import clearance

A7 (Export / Import clearance)

Under CFR, the seller must (at its own risk and expense) carry out all export clearance formalities required by the country of export, where applicable, such as:

- licences or permits,

- security clearance for export,

- pre-shipment inspection, and

- any other authorisations or approvals.

The seller has no obligation to arrange any transit/import clearances.

However, if the buyer requests (at its own risk and cost), the seller must assist in obtaining any documents or information that relate to formalities required by the country of transit or import, such as:

- permits or licences,

- security clearance for transit/import,

- pre-shipment inspection required by the transit/import authorities, and

- any other official authorisations or approvals.

B7 (Export / Import clearance)

Where applicable, the buyer must assist the seller (at the seller’s request, risk, and cost) in obtaining any documents or information needed for all export-related formalities required by the country of export.

Where applicable, the buyer must carry out and pay for all formalities required by any country of transit and the country of import. These include:

- licences and permits required for transit,

- import licences and permits required for import,

- import clearance,

- security clearance for transit and import,

- pre-shipment inspection, and

- any other official authorisations and approvals.

These are the buyer’s responsibility because they occur after “delivery” by the seller.

At first glance, it might seem strange that both seller and buyer are responsible for pre-shipment inspections. To clarify, the seller is responsible if it is a requirement of the country of export, and the buyer is responsible if it is a requirement of the country of transit/import.

CFR A8 / B8: checking / packaging / marking

A8 (Checking / Packaging / Marking)

In all rules, the seller must pay the costs of any checking operations which are necessary for delivering the goods, such as checking quality, and measuring, packaging, weighing, or counting the goods.

The seller must also package the goods (at its own cost) unless it is usual for this particular good to be sold unpackaged, such as in the case of bulk goods.

The seller must also take into account the transport of the goods and package them appropriately unless the parties have agreed in their contract that the goods be packaged or marked in a specific manner.

B8 (Checking / Packaging / Marking)

In all rules, there is no obligation from the buyer to the seller regarding packaging and marking. There can, in practice, however, be agreed exceptions, such as when the buyer provides the seller with labels, logos, or similar.

CFR A9 / B9: allocation of costs

A9 (Allocation of costs)

The seller must pay all costs until the goods have been delivered under A2 (meaning loaded on board the vessel for CFR) except any costs the buyer must pay as stated in B9.

Under CFR, the seller must pay:

- the costs of loading the goods on board the vessel,

- the freight costs,

- any transport-related security costs,

- transit costs or unloading at the discharge port, if these are included in the contract of carriage,

- any costs involved in providing the usual proof that the goods have been delivered, so if the contract between the parties states that proof is a bill of lading, then the seller pays any document fee, and

- any costs, export duties, and taxes, where applicable, related to export clearance.

Further, if the seller requests that the buyer provide any information or documents in relation to customs clearance, then the seller must pay the buyer for these costs.

B9 (Allocation of costs)

Under CFR, the buyer must pay:

- all costs relating to the goods from when they have been “delivered” (meaning loaded on board the vessel for CFR), other than those payable by the seller, and

- any duties, taxes and other costs for transit or import clearance, where applicable.

If the buyer has requested the seller to provide assistance in obtaining information or documents needed for the buyer to effect insurance, and transit and import clearance, then the buyer must reimburse the seller’s costs.

Additionally, if the seller has advised that the goods have been clearly identified as the goods under the contract, the buyer pays any additional costs incurred if:

- the buyer fails to give notice,

- the parties have agreed in the contract that the buyer is entitled to determine the time for shipping the goods or the point of receiving the goods in the port of destination.

CFR A10 / B10: notices

A10 (Notices)

The seller must give the buyer sufficient notice that the goods have been delivered (meaning loaded on board in the case of CFR).

The seller must also give the buyer any notice required by the buyer so that the buyer can receive the goods.

What that notice is will be agreed in the sales contract and might well also refer to conditions contained in a charter party contract of carriage if relevant.

B10 (Notices)

If the parties agree in the contract that the buyer is entitled to determine the time for the seller to ship the goods and, possibly more importantly, the point within the named port of destination where it will receive the goods, the buyer must give the seller sufficient notice.

The contract will usually detail how much notice is to be given.

A1 (General Obligations)

In each of the eleven rules, the seller must provide the goods and their commercial invoice as required by the contract of sale and any other evidence of conformity, such as an analysis certificate that might be relevant and specified in the contract.

Each of the rules also provides that any document can be in paper or electronic form as agreed in the contract, or if the contract makes no mention of this, then the rules default to what is customary.

The rules do not explicitly define what “electronic form” is. This ambiguity means that it can be anything from a .pdf file to a blockchain record or another format yet to be developed.

B1 (General obligations)

In each of the rules, the buyer must pay the price for the goods as stated in the contract of sale.

The rules do not refer to when the payment is to be made (e.g., before shipment, immediately after shipment, thirty days after shipment, etc.) or how it is to be paid (e.g., prepayment, against an email of copy documents, on presentation of documents to a bank under a letter of credit, etc.).

These matters should be specified in the contract.

CFR A2 / B2: delivery

A2 (Delivery)

Under CFR, the seller “delivers” by placing the goods on board the vessel on the agreed date or within the agreed period (if there is no such time notified then at the end of that period) and in the manner customary at the port.

Most importantly, delivery occurs when the seller loads the goods onto the vessel, not when the vessel reaches the destination port.

B2 (Delivery)

Under CFR, the buyer must:

- take delivery of the goods when the seller has delivered them on board the vessel and

- receive them from the carrier at the named destination port.

Most importantly, delivery occurs when the goods are released from the seller’s direct control, not when the goods reach the destination.

The main difference in wording to FOB is simply that with CFR and CIF, reference to the vessel being nominated by the buyer is absent, as is a reference to the buyer nominating a loading point within the load port.

The contract for carriage and cost implications are dealt with in other articles.

CFR A3 / B3: transfer of risk

A3 (Transfer of risk)

In all the rules, the seller bears all risks of loss or damage to the goods until they have been “delivered” in accordance with A2 described above.

The exception is loss or damage in circumstances described in B3 below, which varies depending on the buyer’s role in B2.

B3 (Transfer of risk)

The buyer bears all risks of loss or damage to the goods once the seller has delivered them as described in A2.

If the buyer fails to inform the seller about the destination port (or the point within that destination port), then the seller will be unable to deliver under A2, and the buyer bears the risk of loss or damage to the goods from the agreed date or at the end of the agreed period.

CFR A4 / B4: carriage

A4 (Carriage)

Under CFR, the seller must arrange (or procure in the case of a string-sale) a contract for the carriage of the goods from the agreed point of delivery in A2 to the named port of destination or, if agreed, to any point (quay or wharf) in that port.

The contract of carriage must be made on usual terms that are appropriate to the type of goods and by a vessel normally used for transporting the type of goods by the usual route (often agreed on in the contract of sale) at the seller’s cost.

B4 (Carriage)

The buyer has no obligation to the seller to arrange a contract of carriage.

CFR A5 / B5: insurance

A5 (Insurance)

The seller does not have the risk beyond the delivery point, so it has no obligation to the buyer to arrange a contract of insurance.

However, if the buyer requests (at its risk and cost), the seller must provide the buyer with information in its possession that the buyer needs to arrange its insurance.

B5 (Insurance)

Despite having the risk of loss or damage to the goods from the delivery point, the buyer does not have an obligation to the seller to insure the goods.

Whether the buyer chooses to insure the goods or bear the risk themselves is entirely their choice.

CFR A6 / B6: delivery / transport document

A6 (Delivery / Transport document)

Under CFR, the seller (at its own cost) must provide the buyer with the usual transport document covering transport to the agreed port of destination.

The transport document must cover the contracted goods within the agreed period for shipment.

If it is agreed, then this document must enable the buyer to claim the goods from the carrier at the named place of destination (and in a string sale, enable the buyer to sell the goods in transit to a subsequent buyer by transferring that document).

B6 (Delivery / Transport document)

The buyer must accept the transport document provided by the seller if it conforms with the contract between them.

CFR A7 / B7: export / import clearance

A7 (Export / Import clearance)

Under CFR, the seller must (at its own risk and expense) carry out all export clearance formalities required by the country of export, where applicable, such as:

- licences or permits,

- security clearance for export,

- pre-shipment inspection, and

- any other authorisations or approvals.

The seller has no obligation to arrange any transit/import clearances.

However, if the buyer requests (at its own risk and cost), the seller must assist in obtaining any documents or information that relate to formalities required by the country of transit or import, such as:

- permits or licences,

- security clearance for transit/import,

- pre-shipment inspection required by the transit/import authorities, and

- any other official authorisations or approvals.

B7 (Export / Import clearance)

Where applicable, the buyer must assist the seller (at the seller’s request, risk, and cost) in obtaining any documents or information needed for all export-related formalities required by the country of export.

Where applicable, the buyer must carry out and pay for all formalities required by any country of transit and the country of import. These include:

- licences and permits required for transit,

- import licences and permits required for import,

- import clearance,

- security clearance for transit and import,

- pre-shipment inspection, and

- any other official authorisations and approvals.

These are the buyer’s responsibility because they occur after “delivery” by the seller.

At first glance, it might seem strange that both seller and buyer are responsible for pre-shipment inspections. To clarify, the seller is responsible if it is a requirement of the country of export, and the buyer is responsible if it is a requirement of the country of transit/import.

CFR A8 / B8: checking / packaging / marking

A8 (Checking / Packaging / Marking)

In all rules, the seller must pay the costs of any checking operations which are necessary for delivering the goods, such as checking quality, and measuring, packaging, weighing, or counting the goods.

The seller must also package the goods (at its own cost) unless it is usual for this particular good to be sold unpackaged, such as in the case of bulk goods.

The seller must also take into account the transport of the goods and package them appropriately unless the parties have agreed in their contract that the goods be packaged or marked in a specific manner.

B8 (Checking / Packaging / Marking)

In all rules, there is no obligation from the buyer to the seller regarding packaging and marking. There can, in practice, however, be agreed exceptions, such as when the buyer provides the seller with labels, logos, or similar.

CFR A9 / B9: allocation of costs

A9 (Allocation of costs)

The seller must pay all costs until the goods have been delivered under A2 (meaning loaded on board the vessel for CFR) except any costs the buyer must pay as stated in B9.

Under CFR, the seller must pay:

- the costs of loading the goods on board the vessel,

- the freight costs,

- any transport-related security costs,

- transit costs or unloading at the discharge port, if these are included in the contract of carriage,

- any costs involved in providing the usual proof that the goods have been delivered, so if the contract between the parties states that proof is a bill of lading, then the seller pays any document fee, and

- any costs, export duties, and taxes, where applicable, related to export clearance.

Further, if the seller requests that the buyer provide any information or documents in relation to customs clearance, then the seller must pay the buyer for these costs.

B9 (Allocation of costs)

Under CFR, the buyer must pay:

- all costs relating to the goods from when they have been “delivered” (meaning loaded on board the vessel for CFR), other than those payable by the seller, and

- any duties, taxes and other costs for transit or import clearance, where applicable.

If the buyer has requested the seller to provide assistance in obtaining information or documents needed for the buyer to effect insurance, and transit and import clearance, then the buyer must reimburse the seller’s costs.

Additionally, if the seller has advised that the goods have been clearly identified as the goods under the contract, the buyer pays any additional costs incurred if:

- the buyer fails to give notice,

- the parties have agreed in the contract that the buyer is entitled to determine the time for shipping the goods or the point of receiving the goods in the port of destination.

CFR A10 / B10: notices

A10 (Notices)

The seller must give the buyer sufficient notice that the goods have been delivered (meaning loaded on board in the case of CFR).

The seller must also give the buyer any notice required by the buyer so that the buyer can receive the goods.

What that notice is will be agreed in the sales contract and might well also refer to conditions contained in a charter party contract of carriage if relevant.

B10 (Notices)

If the parties agree in the contract that the buyer is entitled to determine the time for the seller to ship the goods and, possibly more importantly, the point within the named port of destination where it will receive the goods, the buyer must give the seller sufficient notice.

The contract will usually detail how much notice is to be given.

Cost and Freight (CFR): advantages and disadvantages

Despite being widely used in the industry for container transport, CFR is not well suited for this mode of transport – for much the same reason that FOB is also unsuitable.

As with FOB, CFR is often treated as just a price point, and the seller arranges and pays for carriage. Of course, there is more to it than that.

This rule can be advantageous for the seller. It is now responsible for arranging carriage, often by chartering the vessel, and must pay the cost of carriage. As the cost of carriage is an input to the selling price, the seller most likely will add a margin of error and a profit margin, all built into its CFR price. Like FOB, the seller’s risk for loss or damage to the cargo ceases once the goods are on board the vessel, and like FOB, it would be prudent for the seller and buyer to agree in their contract as to how the goods are to be stowed.

The disadvantage to the seller is that it will usually have to pay the freight before obtaining the bill of lading, and thus, typically before payment is received from the buyer.

Just as with FOB, while under Incoterms® 2020, the seller has no risk beyond delivery. If the buyer defaults for whatever reason, the seller will be at risk and would be prudent to investigate some form of contingency insurance.

For the buyer, the advantage is that it does not have to arrange carriage and avoids possibly paying a deposit on that to the vessel owner.

The buyer might consider it a disadvantage that it bears the risk for loss or damage of the goods from delivery, and typically, as with FOB, it would take out appropriate insurance or have arranged an annual policy.

Cost and Freight and letters of credit

This rule works well with letters of credit because, as with FOB, the banks still think the way things were done forty or fifty years ago.

The bill of lading clause will require the document to state “freight prepaid.”

CFR Video – What is the importance of the new Incoterms® 2020 rules in light of Brexit?

“Incoterms” is a registered trademark of the International Chamber of Commerce.

Refer to ICC publication no. 723E for the text.

Publishing Partners

- Incoterms Resources

- All Incoterms Topics

- Podcasts

- Videos

- Conferences