Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

Basel III – A Guide to Basel and what it means for banks

Basel III regulation affects lending from banks. Alternative finance and ‘fintech’ encompass many different elements which are incorporated into lending platforms; it is these lenders that may be affected by the Basel regulations. Prior to looking at this change it is important to understand where we are in the alternative finance cycle.

Many in the world of investment and finance generally talk about the ‘fintech’ bubble, high valuations and replacing the banks. We work at the coalface of the alternative finance market and see that Europe is at an interesting point in the curve or cycle. It is true that alternative lending was phased in with a highly ambitious aim of replacing the banks; this was post 2007 when the general view was anti-large financial institution and capital adequacy requirements increasing. The phase in of alternative capital providers for various structures of lending were mainly grown in the private market and more recently institutional capital has moved in. This has in some respects tied some alternative finance providers to back-to-back requirements or policies and so has been restrictive in some respects, but has also facilitated growth.

Basel II and Basel III – Explained

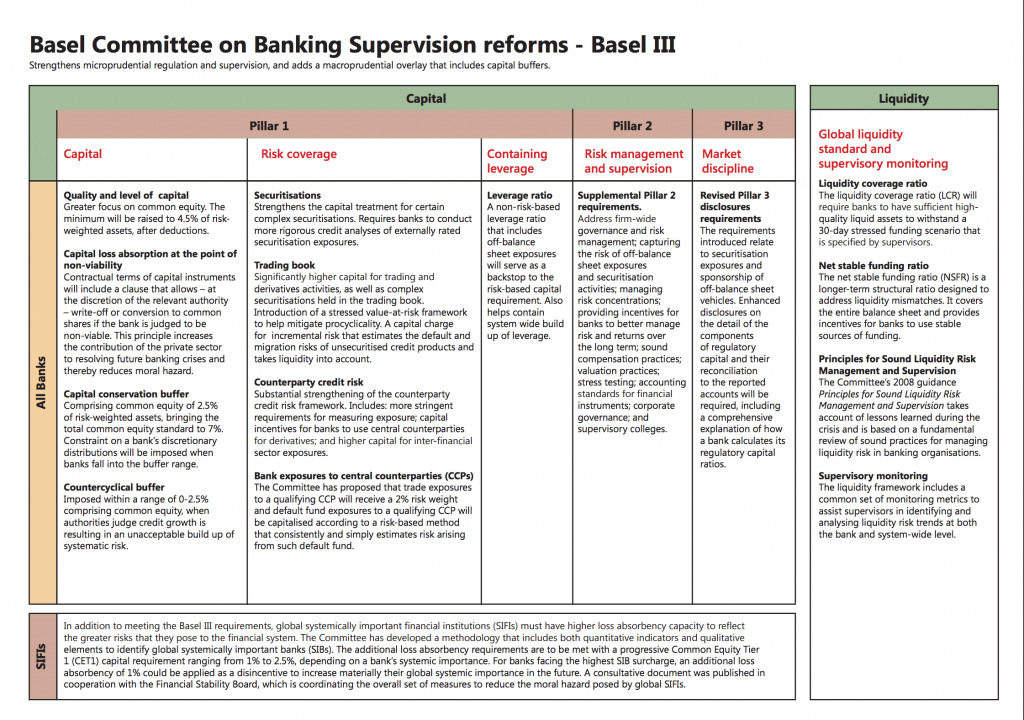

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision decided to phase in Basel III from 2013 to 2019, in order to build on the Basel II regulations. The aim was to increase the hold on risk, regulation and supervision in the banking sector. A main focal point of the regulations is capital requirements in the banking world, which will inevitably impact borrowing costs. Some estimates put the additional capital required by the European banking industry to comply with Basel III at around 700 billion euros; which will reduce the return on equity and mean that banks move away from ‘riskier’ asset classes.

Basel III overview table:

The broad aims of the regulation are to retain the banks’ solvency and tighten risk requirements. Thus, it builds on the Basel II capital adequacy requirements, which limit the amount of assets that a bank may have in relation to their capital. The reason for this, is so that any losses are managed and will not negatively impact the rights of creditors and depositors.

The focus on absorption of losses means that banks are required to have certain risk buckets of capital and a required size of such capital. There are three main tiers of capital; when looking at assets a bank must concentrate on the value of all of the exposures that it faces and a risk weighting is applied depending on the asset type. Thus, an amount of the bank’s regulatory capital must be allocated to each loan and this restricts the amount of business that a bank may enter into. This means that there is a cost in relation to the capital adequacy requirements of any loan being advanced.

The regulations have increased in specification and sophistication; to calculate risk weighting there will be a concentration on the type of counterparty, credit rating; security or risk mitigants in place and regimes for specific areas of finance. Alternative calculation methods with other risk weighting models will also be used.

Basel II allowed the capital charge of a loan to vary during its life. It would look at the credit rating of the borrower and the loan to value throughout the life of the lend. Risk weighting can also be amended if there are regulatory changes. Basel 3 has built on this, as there is an 8 per cent minimum ratio of capital to RWA. The capital requirements are higher and stricter regulatory deductions for calculating Tier 1 capital with tougher requirements for capital instruments, which are not common equity. In relation to the tiers of capital, the innovative features introduced to lower the cost of raising tier 1 capital are to be done away with. Tier 2 capital is to be simplified and tier 3 capital is to be phased out.

Two capital buffers are being added – a capital conservation buffer and a countercyclical buffer. There is a general risk shift from depositors to bank employees and shareholders. In the event that an institution does not have the required capital buffers in place, Basel III may prevent the bank’s ability to distribute earnings.

The capital conservation buffer is to come in by 2019 and is intended for banks to maintain capital levels needed in the event of a sector-wide downturn. The countercyclical buffer is subject to consultation and has the aim of being implemented by national supervisors at times of rapid credit growth in a specific economy, with the aim of slowing such growth.

There is going to be increased capital requirements and minimum liquidity levels. It is presumed that there will be a reduction of rates on retail deposits; staff compensation will be reduced; and margins will be heightened on other products. Lending rates will also reflect these new costs, but in the event that this can’t be fed into older facilities then existing rates of return will be lower.

Video: What is Basel III?

The aim is to reduce the risk of banking collapse at the institutional level and system wide shocks seen in recent years. The risk based capital adequacy framework means that at its very basic level, the greater ‘risk capital buffer’ needed, the less that a bank can deploy to earn a margin. There will be cost of capital increases and due to the restrictions, banks will look for less risky loans to back.

Therefore government debt will remain in favour when compared to more heavily risk weighted SME lending.

The above is contrasted with the light touch approach in relation to regulation when looking at alternative finance firms and their approach to lending with associated risk. Less capital is needed to cover any exposure. As an example, UK peer-to-peer lenders only need to have £20,000 of capital, which will increase to £50,000 in 2016.

We don’t think so. This would open up regulators to criticism of starving SME’s of finance and allow banks to run the market with their own tighter regulatory requirements. The bank referral scheme has been a positive step to not let this happen; businesses turned down for bank finance are being referred to alternative providers by financial institutions, which is a step towards positive policy.

It is suggested that under Basel III banks may have to hold twice as much capital compared to previously. Overdrafts are also beginning to be cut due to their re-categorisation and will be seen in the same way as draw down loans, so sufficient capital will need to cover the unlikely possibility of overdrafts being withdrawn simultaneously.

All of the above combines to make for poor reading for new SME bank borrowers; it is more likely that there will be less lending to keep the level of capital the same as it is presumed that there will not be a sudden influx of capital. Thus, the same level or risk can be retained. The general view of SMEs being higher risk, lower return, and the need of significant resources in order to process each case will impact on the availability of SME lending.

A fear of those investors that try to look ‘ahead of the curve’ and fear coming into the alternative finance market ‘too late’ is that there are overpriced valuations. Many see that there will be consolidation in the industry as transparency will be seen in loan books and those without tough credit policies will be found out as many loan books go full cycle.

We see that regulation phase in will be slow; there are more partnerships with financial institutions and alternative finance will act as a flexible and necessary addition to the main banks. Alternative finance will be perceived as a bolt on and not a replacement.