Estimated reading time: 13 minutes

It goes without saying that 2020 was quite a year, and not in the way that many of us would have hoped for.

It was a year marked by the global spread of SARS-CoV-2, followed by a series of destabilising lockdown policies imposed by panicked governments on the world’s major economies.

Not surprisingly, it took a while for global trade to recover from such disruption, but by the end of the year, things were already starting to look up.

In November 2020, the Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis recorded a 2.1% month-on-month increase in the volume of global goods trade, taking it above its December 2019 pre-pandemic level for the first time.

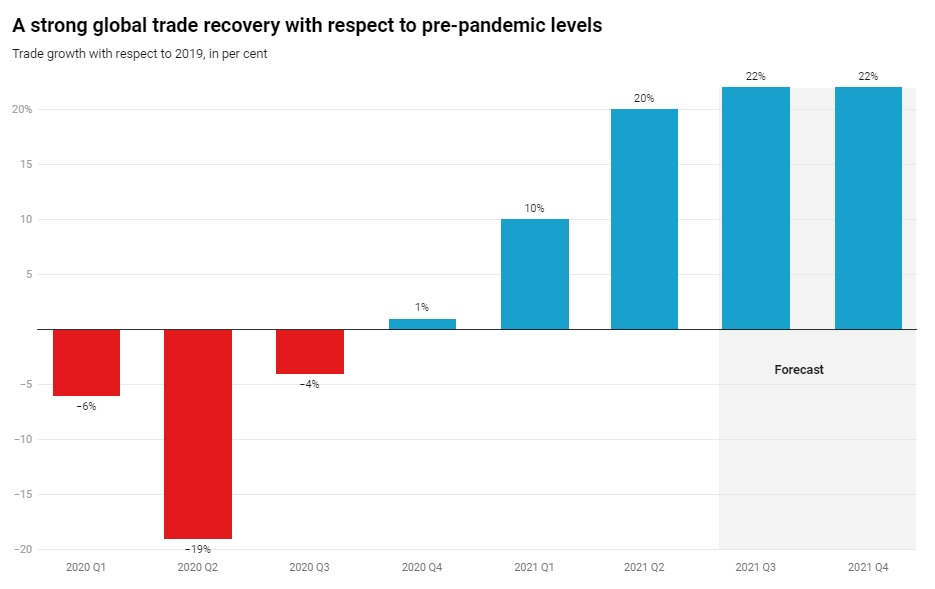

This finding was soon corroborated by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), which found that global trade grew 1% above pre-pandemic levels in Q4 2020, followed by 10% above in Q1 2021, and 20% above in Q2 2021.

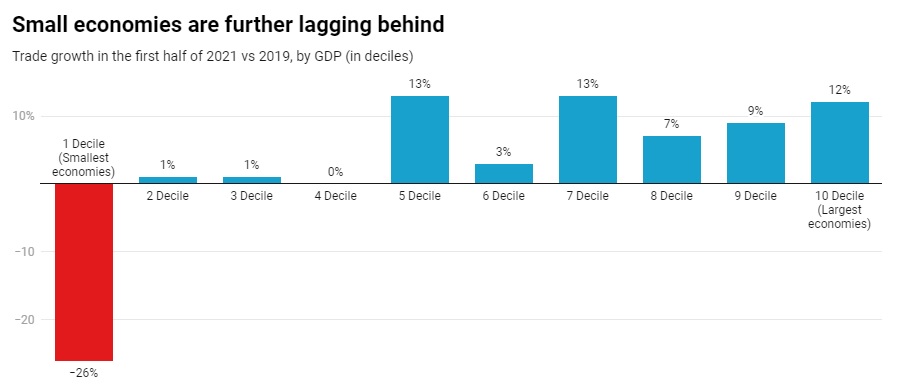

UNCTAD was quick to point out, however, that the recovery wasn’t enjoyed equally by all.

Among the lowest decile of the world’s poorest economies, trade contracted 26% in H1 2021 compared to H1 2019, and exports fell 4% for those economies during the same period.

Nevertheless, UNCTAD sees global trade growth ending Q4 2021 up 22% above its 2019 average, despite ongoing supply chain disruptions, decades-high inflation, and, of course, the virus.

Clearly, then, there is a story as to how a tentative global recovery this time last year went from strength to strength in 2021, so let’s take a look back at some of the highlights along the way.

Around the blocs in 2021 – free trade agreements increase

2021 opened with a flourish for the UK, as the country’s first post-Brexit free trade agreement went into effect on New Year’s Day.

Known as the UK-Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), the agreement was largely based on the pre-existing EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (JEEPA), albeit with a few new additions.

For example, both the UK and Japan drew attention to the digital trade provisions of the deal.

Importantly, the CEPA prohibits restrictions on cross-border transfer of data (including personal data) and imposes a ban on data localisation requirements.

The two countries also agreed to maintain principles of net neutrality; to strengthen provisions on the transfer of financial information between financial services providers; and to commit to not imposing customs duties on electronic transmissions.

Finally, the deal also contains provisions for the protection of source codes and the use of e-signatures.

It is worth noting that many of these commitments are similar to those made by Japan in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which the UK also formally applied to join in January 2021.

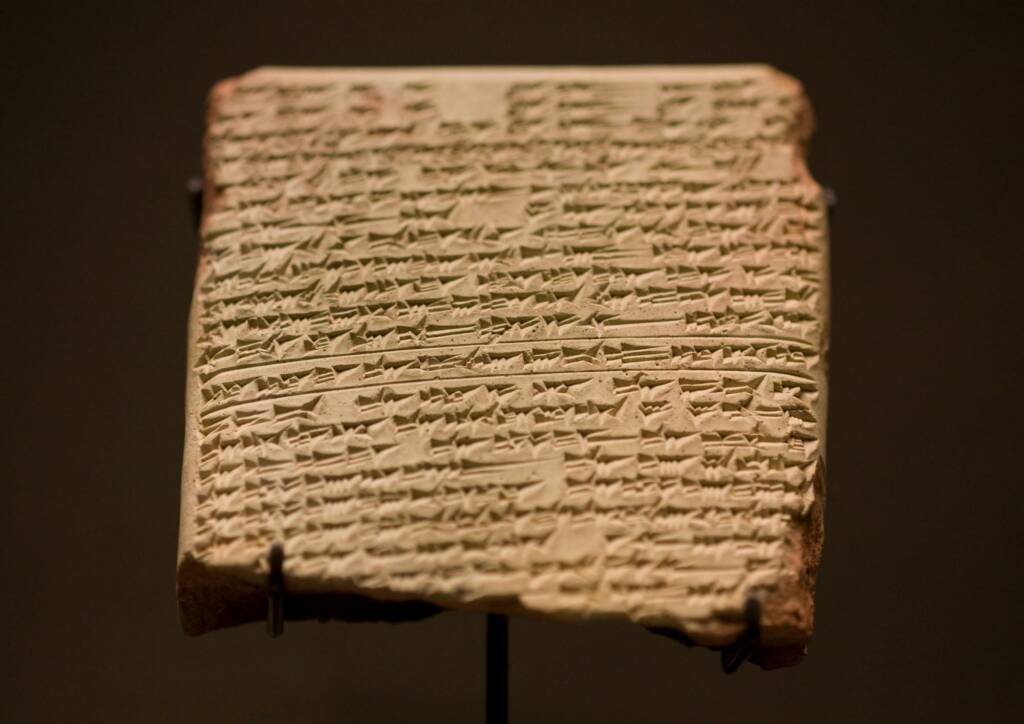

Mesopotamian tablets go digital, proofs of concept go live

Sticking to the theme of going digital, in 2021 we saw the letter of credit – one of the most ancient instruments of trade – undergo a number of modern makeovers.

In February, for example, Finnish technology company Wärtsilä and Swedish bank SEB announced that they had successfully piloted a series of digital export letters of credit (LCs).

As part of a secure data-sharing experiment, the Scandinavian duo implemented a full digital LC document exchange via a Finnish data-sharing platform.

Harri Rantanen, business developer in transaction services at SEB, said the results were impressive: “The prototype was evaluated in January and the result is ground-breaking.

“This pilot will pave the way for further developments where each of the pilot participants will be able to expand the use case portfolio in common or to digitalise the exchange of information within their own value networks.”

Greensill – the Bear Stearns of trade finance?

Of course, no 2021 Year in Review would be complete without at least a passing mention of the collapse of Greensill Capital.

Once a pioneer of trade finance, Australian businessman Lex Greensill had grown his eponymous company to become a major player in the industry, delivering $143 billion in finance in 2019 and 2020 respectively.

Greensill even secured the backing of Japanese investment firm SoftBank, in addition to the advisory skills of former British Prime Minister David Cameron.

But the Greensill empire quickly crumbled in March this year, after Credit Suisse froze $10 billion of funds that included assets originated by Greensill.

As with Bear Stearns in 2007, it was a reminder that things are not always as they seem in high finance, and even the mighty can fall a long way from the top.

Prior to March 2021, the market had believed Greensill to be in good shape. But as it turned out, what investors could see from a distance was merely the tip of a debt-laden iceberg submerged deep underwater.

Even today, 10 months on, the costs of Greensill’s collapse are still being counted, and heads are still rolling.

Just this week, for example, Credit Suisse fired two fund managers who oversaw the $10 billion of Greensill-linked funds mentioned above.

Lukas Haas, a portfolio manager, and Luc Mathys, who was head of fixed income, both saw their suspensions turn to firings after a company investigation was completed.

Suez Canal grinds to a standstill

In terms of raw news impact, however, not even Greensill could match what was about to transpire in the final week of March – in one of those rare trade stories that captured not just the business press, but the entire world’s media.

We’re talking, of course, about the Suez Canal blockage caused by the grounding of the Ever Given.

This week’s cover, “Ever Giving,” by @MarkUlriksenArt. #NewYorkerCovershttps://t.co/GPFYLG0zuX pic.twitter.com/8fE0d7ZYSs

— The New Yorker (@NewYorker) November 29, 2021

Who could forget the image of the 400-metre-long, 220,000-tonne vessel as it lay beached and motionless, bringing one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes to a standstill?

The blockage lasted six days, from March 23-29, and its impact on global trade was severe.

Each hour of the blockage led to a hold-up of around $400 million of cargo, or more than $57 billion over the six days.

But perhaps the main lesson we should take from the blockage is that, when things don’t go to plan in global shipping, bigger vessels create bigger problems.

As Captain Rahul Khanna, global head of marine risk consulting at Allianz, has said: “We need to look more closely at how we can minimise the risks of mega-ships, especially in ports or in bottleneck passages like the Suez Canal or the Panama Canal, given the disruption we have seen that grounding incidents can cause.

“As a shipping insurer we want to support the industry and its growth. We have nothing against ships getting bigger, but all the additional aspects that come with this increase in size need to be considered from a risk management perspective.”

Khanna’s message was seconded by Régis Broudin, global head of marine claims at Allianz, who said that “dealing with incidents involving large ships, such as fires, groundings and collisions, is becoming more complex and expensive from a claims perspective.”

Broudin points to data from the Nordic Association of Marine Insurers (Cefor), for example, which has shown that the most costly 1% of all claims account for at least 30% of the value of total claims in any given year.

“The coronavirus pandemic is putting further pressure on maintenance cycles and margins are under strain, but we shouldn’t compromise on safety standards,” Khanna added.

“We all need to think in more innovative ways.”

From scandals to blockages to the RCEP

Thankfully, April had better news in store after a tumultuous March.

In April, Singapore became the first country to ratify the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), with plans to implement the accord on January 1, 2022.

The RCEP is the world’s largest free trade deal and trading bloc, covering a third of the world’s population and 30% of global GDP.

The RCEP’s members include Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam (who together make up the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or ASEAN), as well as Japan, China, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand.

RCEP members will benefit from tariff-free trade for over 90% of goods traded within the bloc, and preferential access to certain products in selected markets.

Companies within the RCEP zone will also be able to provide services to the wider region and increase foreign shareholding limits.

Climate alarm and financial response

One of the biggest stories of the summer of 2021 was the publication of a United Nations (UN) report on climate change.

In August, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published a report predicting that global temperatures are likely to increase by 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels by 2050, unless the world commits to a net zero target on greenhouse gas emissions. (Here is our summary on what this could mean for trade.)

One major outcome of the IPCC report was that it laid the groundwork for the COP26 agreement to ‘keep 1.5 alive’, which was signed by almost 200 countries in November this year.

Among other announcements made at COP26, we also heard more from British Chancellor Rishi Sunak on the UK’s forthcoming mandatory financial disclosures regime for emissions-producing businesses.

And we heard from UN Special Envoy Mark Carney on his Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), which claims it now has the backing of over 450 firms with $130 trillion in assets, each committed to investing for net zero by 2050.

Make no mistake: the ???? is now there if the ???? truly wants to arrest the #climatecrisis

— Mark Carney (@MarkJCarney) November 3, 2021

Today, through the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero #GFANZ, over $130 trillion of capital from 450+ firms across 45 countries is committed to transforming the economy #COP26

Mind the ($1.7 trillion) gap

The latter half of 2021 was marked primarily by inflation, but also by certain key data from the trade finance industry.

Chief among these data was the publication, in October 2021, of the Asian Development Bank’s (ADB) latest figures on the global trade finance gap.

According to the ADB, the global trade finance gap grew to a record $1.7 trillion in 2020, eclipsing its previous high of $1.5 trillion recorded in 2018.

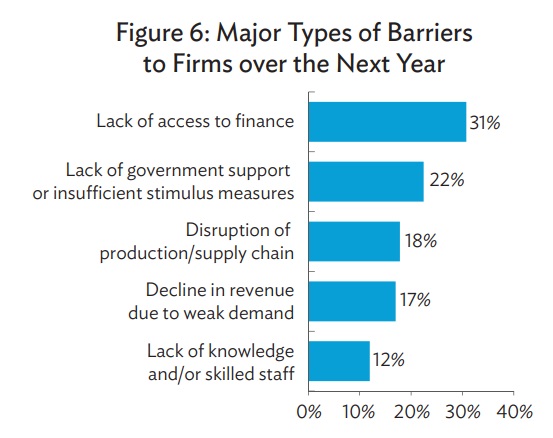

The ADB’s findings also exposed other challenges within the trade finance industry, none of which were particularly good news for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

For example, the ADB found that SMEs, and specifically women-owned SMEs, were significantly more likely to have a trade finance application rejected.

SMEs accounted for 40% of rejected trade finance requests during the pandemic, and 70% of women-owned SMEs reported that their applications had been totally or partially rejected.

As noted above, given that SMEs in poorer economies are suffering the most due to the pandemic, this needs to change.

Welcome to inflation nation

And finally, what would a 2021 Year in Review be without a hat tip to decades-high inflation, making life more expensive and more miserable for all of us, though especially for those on low incomes.

In November this year, the US recorded a 6.7% increase in its 12-month consumer price index (CPI), taking inflation to its highest level in almost 40 years.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the UK’s inflation print fared little better, coming in at a 10-year high of 5.1% for the month of November.

As reported by Trade Finance Global, SMEs on both sides of the Atlantic and in the EU are starting to feel the pinch of this inflation.

One survey found that 92% of US SMEs have seen their costs increase since March 2020, and 82% of US SMEs have raised prices for the end-customer during the same period.

On the plus side, as of November, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell finally retired the word “transitory” to describe US inflation.

#Fed balance sheet on course to $9tn. Has gained another 0.4% to hit fresh ATH at $8.8tn. Fed's total assets now equal to 38% of US's GDP vs ECB's 82% and BoE's 133%. pic.twitter.com/t1ZPyWaymp

— Holger Zschaepitz (@Schuldensuehner) December 25, 2021

But his admission will do little to roll back the 18 months of quantitative easing on steroids that he has presided over, more than doubling the Fed’s balance sheet to a record high of $8.8 trillion since the start of the pandemic.

The Fed’s easy money policies – replicated by the Bank of England and the European Central Bank – are now helping to squeeze margins across the board going into 2022, setting up for a stagflationary period not seen since the 1970s.

That’s a wrap

And there you have it, a 2021 Year in Review from Trade Finance Global.

We would also like to apologise to the many newsworthy stories that didn’t make the cut, and in that spirit, we should perhaps offer some honourable mentions.

Back to the theme of going digital, in October we were delighted to see the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) put a number on the value of digitalised trade.

With legal reform, standardisation, and adoption of digital records, the ICC estimates that the value of trade between G7 countries could rise by $9 trillion by 2026 – a 43% increase above its 2019 value.

As a member of the G7, the UK is certainly taking seriously the opportunity presented by digitalised trade and an increase in digital trade itself.

In November, the SWIFT Standards Release also impacted banks and corporates. With significant changes to MT 760 and MT 767, important guarantee, standby issuance, and letter of credit messages. Steps towards automation and standardisation of bank messages also continue to develop.

This month, in partnership with Singapore, the UK signed the first digital free trade agreement of any nation in Europe, known as the Digital Economy Agreement (DEA).

And to round off the year much like it began, the UK delivered another post-Brexit milestone after signing its first from-scratch free trade deal with Australia, which was announced just before Christmas.

As we head into 2022, financial history will be made, as the LIBOR benchmark, ‘the world’s most important number’, will be phased out.

Though just a fraction of the $230 trillion of existing contracts referencing the LIBOR (and equivalent) benchmarks, its implications for trade and export finance are considerable.

Throughout 2021, TFG worked with ITFA to create the LIBOR for Trade Finance hub, providing updates and guidance on navigating the LIBOR transition.

If you want to take a look back at what you, our readers, enjoyed reading the most this year, do take a look at our 2021 TFG review, here.