On the 11th June, the Group of Seven Nations (G7) met, as they have for some 50 years, to discuss current global economic concerns and plans. The consortium includes some of the world’s wealthiest nations – Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the US and the UK.

According to the US Congressional Research Service, current estimates show the Coronavirus reduced global economic growth to an annualized rate between -4% and -6% in 2020. Global trade is also estimated to have reduced by -5.3% over 2020.

Following on from a year in which global GDP was so heavily impacted, the proposal of a cooperative global corporation tax agreement – which if successful would be the first of its kind – is gaining significant interest.

In a year of extreme national spending, with continued uncertainty, it becomes understandable for a global tax agreement to attract attention. The OECD is believed to be discussing the matter positively, with Mathias Cormann, Secretary-General of the OECD referring to the proposal as a “game-changer”. He went on to state he was “quietly optimistic” about an international agreement on the taxation of multinational corporations.

Who foots the bill?

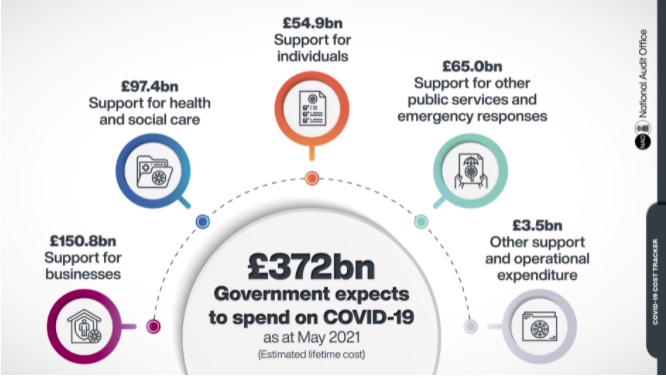

The pandemic caused recessions globally, and the above figures are believed to have been much worse if not for the substantial levels of government support seen across the world, specifically in developed nations. The National Audit Office for the UK states that between February of 2020 and 31st of March of 2021, the UK Government expects a total of £372 billion to be spent on Covid-19.

This is divided between:

- £150.8 billion for support for businesses

- £97.4 billion for health and social care

- £54.9 billion for support for individuals

- £65 billion for public services and emergency responses

- £3.5 billion for operational costs

The US has spent a total of $2.8 trillion, of the initial $4.5 trillion made available in early 2020 through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act.

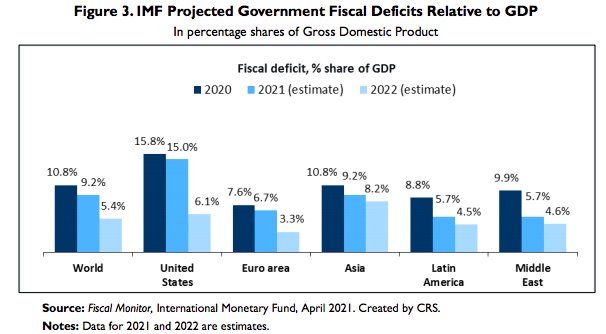

Such large sums of money have had significant impacts on the country’s finances, as the balance increased spending/ borrowing with reduced taxation income. According to the IMF/CRS, Government fiscal deficits relative to GDP were as high as 10.8% for the world economy in 2020, with projections of 5.4% by 2022, which is still comparatively high. To add context, the Parliament Library states that the UK’s average annual fiscal deficit has been 3.6% since 1970.

With nations fiscal deficits at these levels, it is again understandable that a proposal of a corporation tax floor of 15% is palatable, with prospects of increased governmental revenues as a result of the plan.

A Cooperative approach

At the G7 Summit, located this year in Cornwall, there were discussions specifically around global taxation programmes. US President Biden is believed to have driven said talks, with the resulting proposal of a global corporation tax floor of 15% being agreed to by the Finance Ministers of the G-7 nations. This 15% floor is to eliminate the under-cutting of nations.

It is important to understand that much of what governments around the world spent to support their respective economies over the past 18 months, was borrowed. For more information on the UK’s borrowing and debt levels, and the costs of such, see TFG’s article on the 2021 UK Spring Budget.

Given the high debt ratios and borrowing levels, it becomes inevitable that countries will have to increase different forms of taxation to counterbalance the need for borrowing in 2020. This is where US president Joe Biden’s proposal comes in – the theory goes that if all countries have an agreed floor of corporation tax, when nations increase taxations, the corporations will be less likely to ‘move’ their business abroad to benefit from tax reliefs.

Current Global Taxation

There are two main elements to the agreed global corporation tax – firstly, countries which consume the goods/ services of the most profitable multinational corporations will be entitled to tax said corporations. Secondly, all participating countries impose a minimum corporation tax floor on the global income of multinational corporations.

The proposed 15% corporation tax floor figure, will apply to multinational corporations in each individual country – eliminating the process of moving profits into ‘tax-havens’ through subsidiaries.

As of 2021, all 7 members of the G7 have higher corporation tax rates than the proposed floor (Canada 26.5%, France 28%, Germany 15.8%, Italy 24%, Japan 30.6%, US 21% and the UK 19%). This proposal is then toward the world’s economies.

Currently, Country A may have offices and sell product in the US, buy parts and sell product to China, but move profits through legitimate processes into accounts in, the British Virgin Islands for example, in which there is no corporate income tax. Some tax havens do not require a person’s residency, nor any business activity to allow said business to register and pay that countries tax requirements (or lack thereof).

The end result is some of the largest corporations in the world actually pay relatively small amounts in tax. Amazon for example, has paid an effective US federal tax rate of 3% on profits totalling $26.5 billion from 2009-2018. Apple filed an effective global tax rate of 14.4% on financial statement profits for 2020 – lower than the 21% stated above, illustrating the benefits of international tax initiatives.

The newly proposed global tax agreement would mean that companies that qualify for the above criteria would then pay tax in countries which consume the goods/ services. With the above example of Country A, they would then be subject to taxation from the US and China (should China join the agreement) as their good is also consumed in China.

Reuters reported that Alphabet Inc., the parent company of Google, could see their global tax bill increase by as much as 7% on it’s $7.8billion global bill in 2020.

Will it work?

There are multiple caveats to this proposal, and a lot of moving parts that would need to contribute to the successful implementation of such a global programme. Firstly, there will be countries that do not agree with this proposal and, therefore, will not implement it.

For a price floor of any kind to work, by definition you need full participation. Within a single country, this may be ensured through laws/ regulations. Implementing this on a global scale is then difficult, as some nations may choose to keep their tax requirements ‘attractive’ which would lessen the efficacy of the programme.

Secondly, the announcement of this global tax agreement is applicable to roughly the largest 100 companies with profit margins over 10%. How this then gets concretely defined and agreed, is still up for debate. To use Amazon as another example – in 2019 they reported a net income of $3.6 billion, and $4.4 billion of operating profit, which represented a profit margin of just over 7%. Would Amazon therefore not be subject to the new tax responsibilities, despite operating in 58 countries (as of 2018) and being ranked 10th on the Forbe’s list of the world’s wealthiest companies?

There is also a question of who this benefits. Recalling the coincidental time of this announcement, the fact that many nations will be looking to increase taxation revenues over the coming years, some speculate that this is a method that would benefit larger economies more.

As reported by the Financial Times, Mathew Gbonjubola, Nigeria’s ambassador to the OECD said: “What I understand, with the . . . rules as currently being developed, is that developing countries may get next to nothing.”. Mr Gbonjubola went on to state that the US has not yet provided any economic reasoning behind targeting 100 companies only – far less than previous OECD proposals.