The nature of Xi Jinping’s political hegemony has altered China’s conduct and outlook of international trade; based on China’s economic past, what could this spell for the future?

The Globalising Chinese Economy

China has consistently been at the height of trade and economic news for the last half-century. While some scholars see China’s rise as a threat to the global balance of power, analysts tend to debate how long China can keep up its impressive growth rate, after the past 50 years of development.

From Maoist beginnings within the 1950s to the Jinping incumbency; China’s establishment has consistently demonstrated the powerful ability to shift in its regime and economy in a persistent manner, with trade expansionist policies at the core.

Before Jinping’s incumbency, China had begun to demonstrate a willingness for the international alliance. This was through the establishment of the China-ASEAN agreement and the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement. These trade agreements showed that China was experiencing a shift in its trade policy. This shift was towards a more open, free form of trading with other states within the international arena. This allowed China to cooperate with other states within growing globalisation and the international economy.

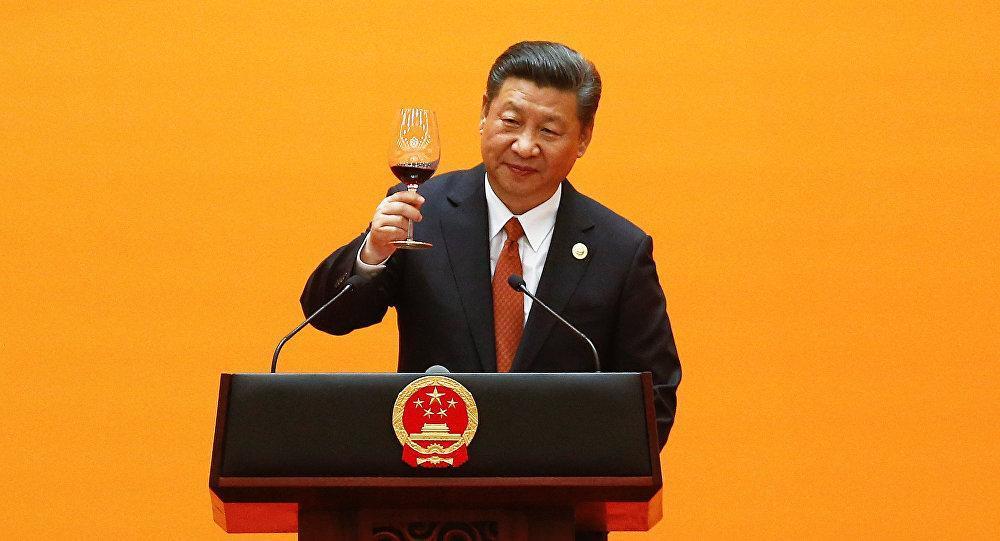

Since assuming office in March 2013, the Jinping administration has pushed for greater free trade and the expansion of globalisation. This was demonstrated when President Jinping vowed to open China’s economy and further support international globalisation. This action has proven to be valuable for the Chinese economy as foreign trade has been described as the main reason for the economic advancement of the country within the past decade.

China’s Imports

Effective and beneficial trade provides a reliance-based relationship where one actor wants or needs goods or services from a second actor. These goods and services could be something which the state cannot produce themselves and must have imported. Thus, a relationship is formed on the basis of providing and offering what other actors want or need.

The figure above depicts the largest sectors which China imported. Machines in the form of telephones, gas turbines, valves and office machine parts make up 30% of China’s imports, the largest amount. This is followed by the import of mineral products such as crude oil, iron ore, coal and petroleum gas. These are goods which China cannot produce itself and instead must be imported. As the 2nd largest importer in the world, China imported $1.52T in 2017.

China imports from the following states:

- South Korea (11%)

- Japan (9.8%)

- United States (9.2%)

- Germany (5.7%)

- Australia (5.6%)

President Xi Jinping has previously established the importance of upholding international alliances, this can be seen through China’s trade policies. Through trade, China has demonstrated international cooperation and inter-reliance within a globalised international economy.

Export Expertise

The power of mass production at home has not been demonstrated by any powerful state other than China. With a growing population of 1.4 billion, a strong workforce has acted as the catalyst for economic expansion.

China is an established exporter of the following:

- Machinery (43%)

- Constituting of computers, broadcasting equipment and telephones.

- Textiles (12%)

- Metals (7.3%)

- Chemical Products (4.6%)

- Transportation (4.5%)

Recent findings demonstrate that China provides 7.5% of the total world exports, equating to a value of $2.06 trillion; it is the world’s largest exporter in goods and services, followed by the United States.

In 2017 the top exporting destinations of China were:

- United States (20%)

- Hong Kong (11%)

- Japan (6.5%)

- Germany (4.5%)

- South Korea (4.1%)

Looking at the continental level the Chinese export shares are the following:

A rapid growth in ‘Made-in-China’ goods demonstrates the feeding back of profits made from exports, towards China’s own workers that made the products and benefiting provincial economies.

China’s industry-oriented economy is fueled by its 150 million factory workers; this extensive number of employees allows companies to mass-produce goods, for a cheap price. Other states such as the United States, France or Canada cannot replicate this large-scale production to the extent to which China has mastered it. These goods are then imported overseas as other states have the unfulfilled need for such a fast-paced form of goods production. Through this expansion, the now worldwide Chinese commerce has boomed due to the greater demand for quickly made goods.

As of recent occurrences, China has suffered a fall in imports and exports in June due to higher US trade war tariffs.

The Price of Trade

The figure above indicates the trade balance in China between the years 1995 and 2017. The red line dictates import and the blue line dictates the export. In 2017, China had a positive trade balance of $873B in net exports. For comparison, the trade balance in 1995 was just $79.8B (around 11 times less).

China has demonstrated exceptional trade and economic power in recent years, with many scholars encompassing these powers as part of Jinping’s establishment. The way in which China has achieved such a reprisal in its economy and trade is to be commended. But, what lessons can we draw from these actions and the current economic and trade status of China?

China could easily stop trading with other actors and due to its strong internal manufacturing industry, could most likely sustain itself for a surprising period of time before its collapse. Other states should look towards achieving what China has accomplished; namely, greater reliance on its own citizens in producing home-manufactured goods.

However, by choosing to trade China opens itself both economically and politically to international alliances. The promotion of international cooperation that China has demonstrated within the last half-century was a drastic shift in its external policies.