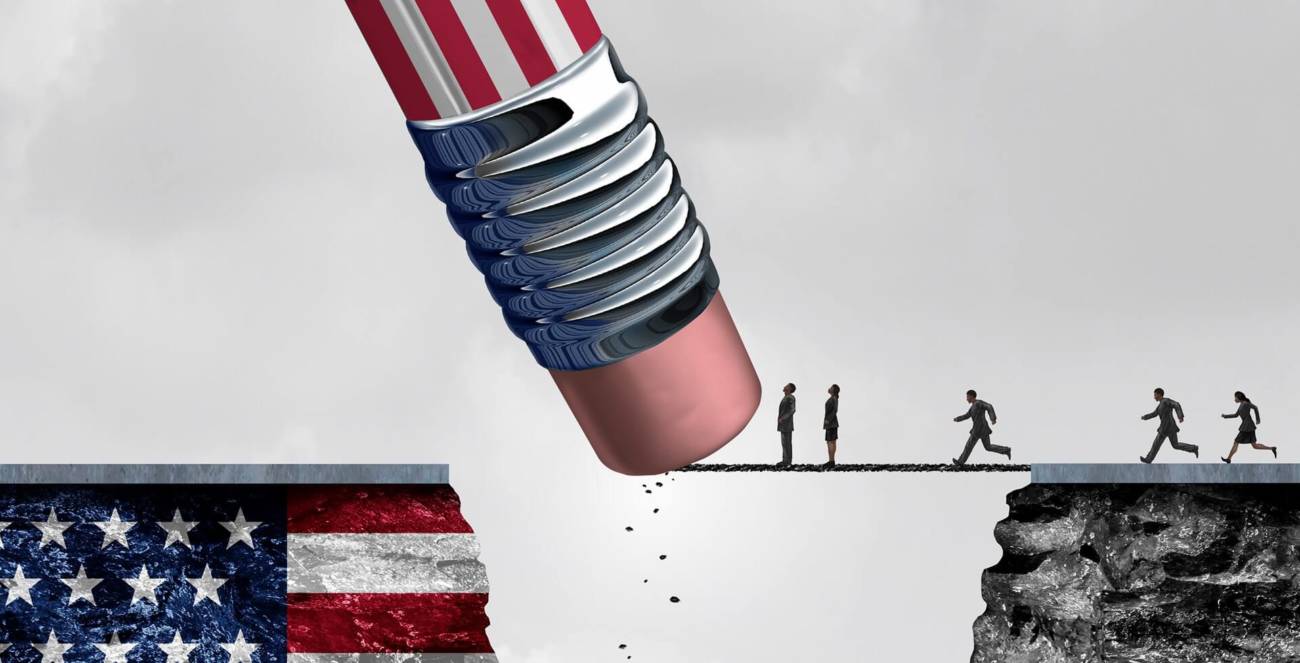

Is protectionism good or bad? It is indeed true that in the past, protectionism as a concept has been used with a net benefit, but often it is perspective that is key.

An example would be the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) put in place by the EU. Erected in the early 1960’s, the programme was aimed at supporting European farmer’s incomes. Has it supported the income of Europe’s agricultural industry? Yes. Have farming industries elsewhere who could well trade with the EU if it weren’t for CAP, suffered a loss from its existence? Yes.

Protectionism comes in many different forms. Most notably with a tax on imports from certain countries. However, the below shows each type of protectionism:

- Tariffs – a tax on imports

- Quotas – an actual limit on the amount of an import

- Embargoes – a complete ban from trading either with a whole nation or just a type of good.

- Subsidies – a financial aid from a governing body to a business/ institution.

- Administrative barriers – these basically add to the cost a business has to front to trade there. By increase, say the complexity of documentation required to trade in the country, it may put businesses who are looking to infiltrate the market off.

There have been many reasons in the past for countries to partake in protectionist protocols. In some cases, it can be fully justified. In the instance of infant industries or emerging markets, it may well be key for the development of an economy for that particular market to succeed. It can also allow time for the concept of comparative advantage to form within a developing industry, which may benefit other countries in the long run.

Protectionism also does result in an increase in domestic employment levels. With higher prices for foreign goods, people turn to domestic goods. So temporarily, employment levels and domestic demand do rise. This temporary rise in domestic employment was seen present in the recent US economy. As they have put more protectionist measures on their international trading platform, GDP growth has increased. In November of 2016, GDP growth was 1.5%. by July of 2018 it has reached 4.2%. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics release on April 5th, the unemployment rate has remained unchanged at 3.8% for the third consecutive month.

This being said, history’s examples have showed us that protectionist measures often end in a decimated employment rate for nations. The Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930 resulted in a 5.5% increase in the unemployment rate, which translates to almost 7 million people, and that was just in the US.

Chicken Tax & Banana Wars

Some other examples of Protectionist policies put in place:

- Banana Wars: For over 6 years, a trade war took place between the EU and the US about the production of Bananas. The US filed a WTO complaint against the EU, highlighting the EU scheme which gave banana producers from Caribbean former colonies unique access into European markets.

The World Trade Organisation ruled that this was indeed not fair, and the EU had to amend its rules. For a substantial amount of time, imports from Latin American were subject to $141 per tonne of bananas tariff.

- Argentina Food Tariffs: Through Argentina’s place in MERCOSUR (an economic trading bloc comprised of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela) many import tariffs have been drastically reduced. However, since July of 2012, any imported goods that directly compete with locally produced goods face a 14% tariff.

- US ‘Chicken Tax’ of 1964; Automobile tariffs: For over 50 years the US held a 25% import tariff on any light trucks or two-seat SUV’s. Interestingly, that import tariff helped secure the place of something referred to as ‘the big 3’ – Ford, General Motors GM and Chrysler. The tariff protected the domestic industry and due to the particular high barriers to entry to the automobile market, the protection fell largely to the three largest producers in the US.

Called the chicken tax because, ironically it was put in place as a retaliation to French and German import taxes placed on American Chicken.

Trade Integration

On the other side of the table, we have trade integration. This has come in many forms, globalisation, the increase in massive scale trade agreements such as the European single market, and more recently the increase in the southern Asian market.

Trade Finance Global recently sat in at the International Chamber of Commerce’s Annual Meeting in Beijing. In this speech, sat Deborah Elms, Executive Director, Asian Trade Center and Vice-Chair, Asia Business Trade Association (ABTA). Speaking on the recent inclusion-inclined behaviours of Asian governments, Deborah presented a feeling of confidence about the state of Southeast Asian trade integration.

As an example, Ms. Elms mentioned the signing of the 27th round of Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which includes the signatures of Hong Kong, Australia and the following 14 other countries;

- Australia

- Brunei

- Cambodia

- China

- India

- Indonesia

- Japan

- Laos

- Malaysia

- Myanmar

- New Zealand

- Philippines

- Singapore

- South Korea

- Thailand

- Vietnam

RCEP has been birthed by these member countries to strengthen the economic linkages, and to enhance trading and investing related activities, alongside minimising any gaps in development amongst the parties (Association of Southeast Asian).

The real strength of RCEP as a trade agreement is its member’s weight in the global economy. Between them, the 16 nations account for just shy of half of the world’s population. With that population, they contribute almost 30% of global GDP and over a quarter of world exports.

Deborah Elms then went onto mention the CPTPP. Published on the Gov.uk website, a press release entitled “CPTPP will be a ‘force for good’ in promoting free trade”. According to the statement, International Trade Secretary Dr. Liam Fox welcomed the introduction of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Pacific Partnership. (CPTPP).

This agreement has been drawn due to tensions that have arose in the pacific area, stemming from the protectionist measures that have been put in place by regions such as the US and China (as mentioned above).

“87% of Chinese exports are subject to distorted trade measures in the US market and 92% of US exports are subject to distorted trade measures in the Chinese market”

The CPTPP, consisting of 11 member nations (see below list) is set to remove 95% of tariffs on goods traded between them and has been explained by Dr Liam Fox as “in all of our interests to ensure an open and rules-based trading system wins out and that a trade war in the pacific does not hit British households in the pocket”.

The mention of a rules-based system prevailing is interesting. Rule-based multilateral trading is something that has been the engine behind 70 years of undeniable job creation, which has greatly elevated the poverty rate. It allows a number of nations to strike trading agreements with one another that intertwine within the countries. Country A may agree to allow x amount of good Y through at a cheaper rate, so it is easier accessible for Country B, if Country A is set to receive some benefit from doing so.

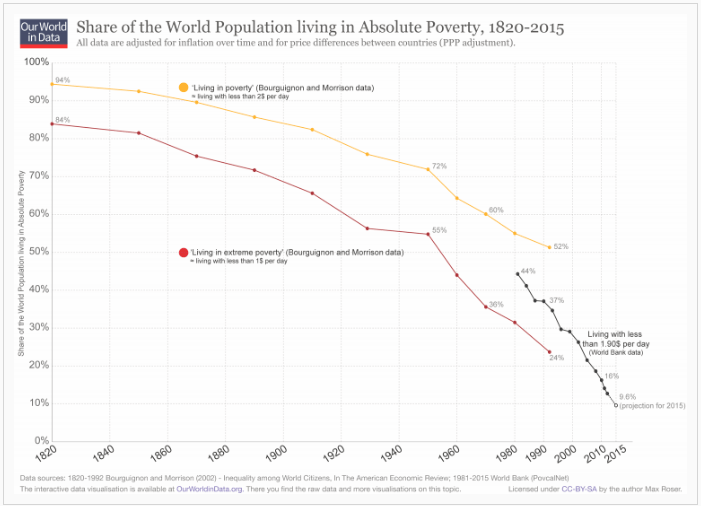

According to the below graph, created by OurWorldInData using data from both the World Bank and a study conducted by Bourguignon and Morrison (2002) displays this reduction in global poverty.

From the above illustration, we can see that within the last two centuries, there has been a steady decline in the presence of absolute poverty in the global economy falling from 84% to 9.6% in 2015. If we look more specifically at the last 70 years, we see a much sharper decline. In 1960, there was 72% of the global population (over 2 billion people) living with less than $2 a day. In the same year, there was 55% of the global population (over a billion and a half people) living with less than $1 a day.

Move forward to the most recent data available here, in 2015 there was 9.6% of the world population living with less than $1.90 a day. There have been advancements in technology, medicine and general societal behaviours which have all contributed toward this decline in global poverty levels, but the rise of globalisation and international trade holds an undeniable place in the list of influences.

Theory Vs. Reality

It cannot be denied that countries, and the citizens within them benefit from an increase in international trade. The concept of Comparative Advantage was first coined by David Ricardo, a British political economist in 1817.

To explain the theory fully, we will look at two example economies:

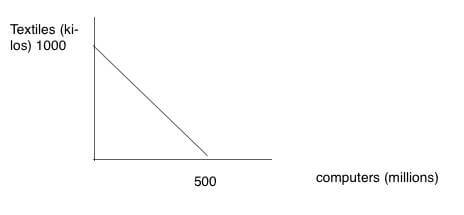

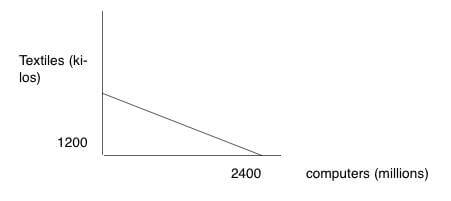

In the above diagram, we see a country having resources to produce either 500 million computers, or 1000 kilos of textiles. We could compare the two by saying the relative price of computers in terms of textiles is

– Price of c / Price of t = 2/1.

For this country, we can see they have the available resources to make far more computers than textile goods. From this, we can recognize that computers are relatively cheaper to produce in developed countries, and they have the comparative advantage in computers. Also, vice versa, the lesser developed countries have the comparative advantage in textiles as they are ‘less bad’ at producing them.

Such a difference between goods would indicate a difference in technology, as the two countries in question are at different stages of development, this would be a good assumption to take (that the more developed country has better technology). The gaps in technology and how far ‘developed’ a country is can be extremely large in some cases, which may lead a country to have an ‘absolute advantage’. An absolute advantage is where country A is that advanced, in terms of capital, labour and technology, that they can produce everything that country B can produce, but cheaper and more efficiently. In these cases, (such as India over the Philippines due to low labour costs of abundance of labour) country A would want to select which sector they supply the best into in terms of efficiency.

The effects of increased comparative advantage are for the most part seen to be beneficial for everyone. By better allocating resources, individual countries produce goods more efficiently, have access to larger markets and so theoretically, produce more goods and experience a higher level of trading, therefore higher quality of life.

Recent realities

The welcoming of protectionist measures; import tariffs and tit-for-tat trade wars directly discourage the above benefits. Not only do they encourage the decline of global trade, they can also promote criminal behaviors such as smuggling in order to avoid paying the excesses. Another reality to bear in mind is that the consumer market suffers just as much, if not more than the producer market from the erection of trading tariffs, which results in a deadweight loss.

So, with protectionist measures on the rise on the large global scale, it is important to keep in mind those new structures that are being put in place and agreed upon, alongside the reform of longstanding agreements.

The advantages of having multilaterally beneficial trading agreements have been showed time and time again, but the world economy will always encompass the political playground of the nations. Sometimes, this will result in trade – specifically the power of restricting the benefits of trade – being manipulated which leaves us with the negative as well as some of the positive effects from protectionism.