“A trade war is the economic equivalent of pushing the nuclear button” – Rebecca Harding, Chief Executive Officer, Coriolis Technologies

President Trump entered office in November 8th, 2016. Throughout his campaign, he held a very strong and very vocal position on the trading relationships that the US held with the rest of the world – that it was not good.

Whether this was the case or not, once in office Trump took on most of the world and it has had severe consequences across the board. The below list shows where the most significant trading tensions have arisen, something that will be more deeply explored further down.

- US and China

- US and the European Union

- US and Canada

The tensions that have escalated between the above parties have resulted in massive fluctuations in global trade patterns, along with an overall declining rate of global trade. The volume of global merchandise trade is forecast to fall to 2.6% growth, down from 3% in 2018.

World Trade Organisation’s Director-General Roberto Azevedo said on 2nd April 2019 that “Trade cannot play its full role in driving growth when we see such high levels of uncertainty”. (WTO) Of course, with events such as Brexit, US Trade wars and other type of political disruption comes a great deal of uncertainty. This uncertainty is the reason behind the change in global trade. Much like the value of a fiat currency, trade depends largely on a certainty of profit.

When uncertainty is provided on an international political level, it disrupts companies on almost all levels. Currency fluctuations, regulation movements, supply chain affects and differences in recruitment capabilities all take a business’ ability to plan and throw it out the window. This has been the largest issue facing British companies over the last two years.

US vs. China

With regard to the aforementioned fluctuations and decline in global trading patterns, the American-Chinese trade war is certainly a key player. America account for 15.12% of global GDP and traded $5.2 Trillion worth of goods and services with the rest of the world in 2017. China on the other hand, account for 18.53% of global GDP and traded $4.28 Trillion in 2017.

The threat that trade wars pose to the world economy is nothing short of devastating. As Rebecca Harding, Chief Executive Officer, Coriolis Technologies recently said at the ICC Annual meeting in Beijing “A trade war is the economic equivalent of pushing the nuclear button”.

A good example would be to look at the last Trade War America was involved in – The Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930. America raised tariffs on all countries exporting to them in an attempt to protect domestic employment and production levels (De ja Vu?).

900 import tariffs were increased by an average of 40-48% (Kimberly Amadeo 2018) which many believe largely deepened the Great Depression and contributed toward the build-up of World War II.

The result? A 40% fall in imports over the following two years which had disastrous effects on the exporting economies – European countries in particular. The American Tariffs were met with equal tariffs from the original victim countries, resulting in a trade war.

American exports fell by almost $2billion dollars, resulting in a 5.5% increase in unemployment from 1929 – 1930 – almost 7 million people lost their jobs as a result of apposing tariffs being raised in retaliation, and that is just in America.

First move

What brought on this trade war? A large imbalance between the trade conducted between the US and China. In 2018, the US exported $120 million worth of goods with China, however, they imported a colossal $539 million worth of goods which leaves quite the deficit.

Trump argued this imbalance stemmed from deals that were struck with China by the previous administrations. These deals lead to the rise of Chinese protectionism alongside intellectual property theft which were – according to the Whitehouse Administration – harming US production levels.

And thus, began the trade war. Trump raised $34 billion worth of import tariffs against China, who then retaliated with import tariffs of 25% on 545 U.S products – also equalling $34 Billion. Following this, a further two more rounds of tariff impositions occurred, resulting in a total of £191bn worth of tariffs.

It is important to highlight that China have only erected tariffs as a retaliation, and not initiated any rises, this is why many believe it is a political negotiating technique.

The problem then arises when the concept of raising tariffs is weaponised to compensate a lack of competitiveness – how far can this go? We saw previously how the US was affected from a tit-for-tat trade war in 1930 with Smoot-Hawley, but in the modern-day trading model where so much is moved across oceans and so many countries fully rely on certain imports, the impact would be ten-fold.

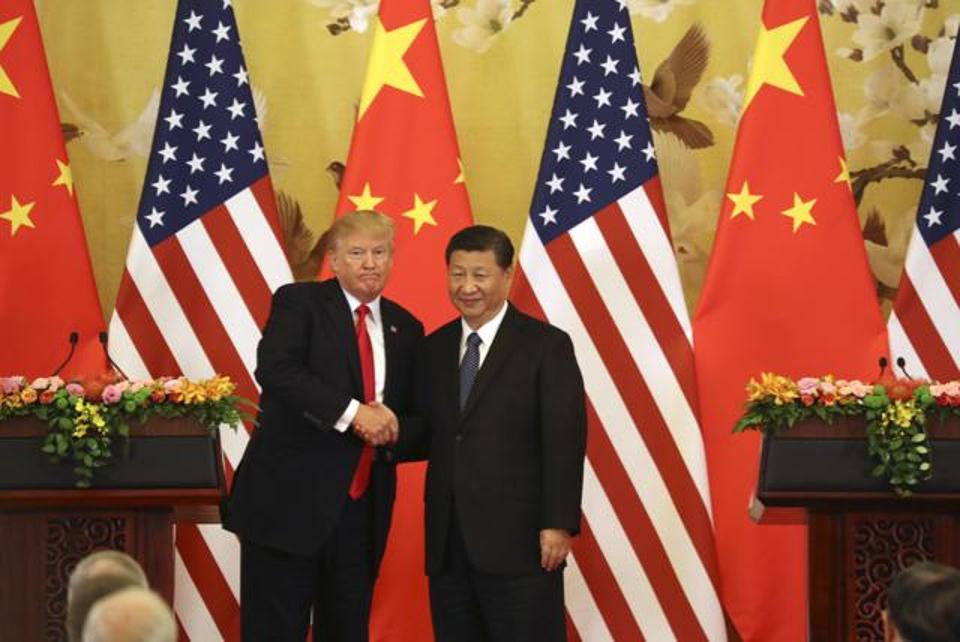

In December of 2018, President Donald Trump and his Chinese equivalent Xi Jinping agreed to halt their trade war, for a limit of 90 days to make room for resolution negotiations. Politically, some may say a smart move from Trump. In a Whitehouse statement, it was said that “at the end of this period of time, if the parties are unable to reach an agreement, the 10 percent tariffs will be raised to 25 percent.” (Whitehouse). This puts clear, public pressure on the Chinese administration to make more effort to reach an agreement.

In the days since the 90 day agreement to not further the trade war, Trump and Jinping have met, and had a “highly successful” meeting, to quote the two Presidents themselves.

The increase of any trade tariffs has been halted by Trump. This means the aforementioned £191bn erected against Chinese goods does still stand, but no further tariffs will be created. What’s more, Xi Jinping has agreed to purchase a “not yet agreed upon, but very substantial”, amount of agricultural, energy, industrial, and other product from the United States to reduce the trade imbalance between the two goliath nations. (Whitehouse)

US vs EU

President Trump announced earlier this month that the US will be implementing import tariffs on $11bn of European products. This is the latest addition to a 14-year long fight over subsidisation. Trump and his administration believe that the subsidies received by Airbus from the EU adversely impacted the United States counterpart Boeing, and their aviation industry and therefore is impacting profits made and taxes paid.

This being said, it cannot be ignored that a WTO investigation into the subsidization activities of the EU-Airbus had in fact found illegal funding being provided to Airbus to fund production of several of their aircrafts.

This $11bn is believed to be drawn upon European goods such as Jetliners, Cheese, Wine and Motorcycles. When the Office of US Trade Representatives released the figures, the EU came back strongly saying the numbers were “greatly exaggerated” and were preparing themselves to hit back at the US. Much like we saw with Chinese retaliation, the European Union have already targeted proposed tariffs of up to $12bn of US imports.

This $12bn of proposed tariffs is to join the current 2.8 billion euro import tariffs that the European Union erected in retaliation to the steel and automobile tariffs put in place back with the Obama administration.

This is not good news for the global trading platform. Essentially, the US wanted to impose the $11bn tariffs as a sort of compensation for the damages the American aviation incurred due to EU aid to airbus. If the EU then raise the equivalent of $12bn on US imports, it is almost guaranteed that the Trump administration will increase the tariffs once more and where will it end?

*”Trade wars are good and easy to win” – President Trump (2018)

When a country (USA) is losing many billions of dollars on trade with virtually every country it does business with, trade wars are good, and easy to win. Example, when we are down $100 billion with a certain country and they get cute, don’t trade anymore-we win big. It’s easy!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 2, 2018

In a tweet posted back in early 2018, Trump wrote “trade wars are good and easy to win”. As we saw with the Smoot-Hawley, this was indeed not the case. Thanks to a study conducted by ING, we can see the statistics behind Trump’s statement;

EU exporters pass on a lower percentage of Increased Costs to their customers than Americans do. What does this mean? It means that when each side of the table experiences a rise in the cost of production for their goods, it is the American companies who pass on a higher percentage of that extra cost onto consumers – leaving US citizens much worse off.

- Demand falls more sharply in the US as a reaction to foreign prices rising by 1%. What does this mean? It means say both the EU and the US impose a 10% import tariff on either one. The overall aim of a trade war of course is to protect the domestic market/ production lines. Therefore, if 10% tariffs are imposed, and your country has a more responsive rate of demand, you will be worse off.

- Essentially, America have started a trade war in which they are more reactive to.

There is a WTO meeting set to be scheduled within the next few months, which will finalise the level of countermeasures the US will be granted to raise against the EU.

US vs. Canada

The trade war enacted between the US and Canada is one of substantially less weight. With Europe, we were talking billions. With China, it was hundreds of billions, but with Canada we are talking millions. An important case study of Trade Wars and the implications of the average joe in the community, nonetheless.

As mentioned earlier, the construction of import tariffs and trade wars are most often done with political end goals in mind, not economic. With regard to this American-Canadian war, it has been put forward to the relevant publics with interesting standings.

President Trump has imposed his tariffs on a sort of heroic platform, telling US citizens that they have been losing for years, and that his tariffs and sanctions are there to help them finally win, whereas Canada’s Justin Trudeau is taking the position that his retaliatory tariffs are “an eye-for-eye lesson against a bullying superpower”. Both are humble motives, whether they are the genuine reasons behind the tariffs or not.

So, what has happened? In March of 2018, Donald Trump announced tariffs of 25% on steel, and 10% on aluminium imports. This announcement, however, did temporarily exclude Canada (along with Mexico) to allow time for negotiations surrounding a redraft of the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) – something Donald Trump has been very vocal about needing to happen for US prosperity.

NAFTA renegotiations took longer than expected, and after being extended to allow for further communications, the exemptions were lifted, and Canada was then liable for the steel and aluminium export tariffs. In response, Canada implemented retaliatory tariffs on US produce that covered $12.8bn worth of products.

The New NAFTA – USMCA

A new Northern Atlantic Free Trade Agreement was reached and renamed to the USMCA – United Sates-Mexico-Canada Agreement on 30th September 2018, replacing the old NAFTA which was agreed in 1994. However, the signing of this agreement brought no truce for Canada in the tariffs raised against steel and aluminium.

This obviously brought frustrations from within the Canadian business community, as confusion over the state of the tariffs raised caused great uncertainty that – as previously mentioned – puts great strain on the economy.

As a result of this strain, many Canadian steel and aluminium industry workers have suffered. On December 15th, Tenaris Algoma Tubes made 90 staff redundant as part of their three-week shut down operation. The site is in Sault Ste. Marie, a city situated close to the US border.

This layoff from Tenaris is not the first. When the tariffs were first put in place, 40 employees were let go from the site. This was because before the tariffs, many were hired to allow the business to continue meeting its demand – much of its US. When this demand was implicated, it no longer became profitable “The implementation of a tariff has created an unsustainable market to serve our U.S. customers,” David McHattie, a vice president for Tenaris Canada. (reuters)

Overview

All of the above is a story of protectionism vs inclusion, something that is at the forefront of some of the biggest global debates happening at this moment in time. Brexit was not done for economic reasons, but political ones. The political choice to take back power, whether the idea holds any merit is another discussion, but the British people wanted power back in their hands. Arguments of immigration and the affects it had on domestic employment levels, whether they held any merit or not were strong enough to influence the outcome of Brexit.

Then on the other side of the table, you have the silver-linings. The new USMCA has brought together three strong economies, which will hopefully provide some benefit from the rest of the world if the theories of comparative advantage and globalisation are to hold true.

For more information on the history, current relevance and effects of protectionism, see Trade Finance Global’s article here.