- The good, the bad, and the ugly consequences of artificial intelligence (AI) have all reared their heads this year, and are demanding attentive analysis.

- The World Trade Organisation (WTO) has today published a report entitled ‘Trading with intelligence: How AI shapes and is shaped by international trade’.

- Comprehensive analysis can inform a truly meaningful set of AI regulations to be built in the future.

When computer scientist Alan Turing invented the Turing Test in 1950 to distinguish intelligence from humanity, the concept of AI was received with enthusiasm and curiosity about technology’s unexplored consequences. Decades later, when ChatGPT3 was launched to the public in 2022, its adoption was equally fervent.

AI has resulted in multifaceted and unexpected international trade developments—but summarising its impact in one word, AI has become ubiquitous. The WTO’s first comprehensive report on AI comes at this crucial juncture.

“The future of trade is services; it’s green; it’s digital; and it should be inclusive”

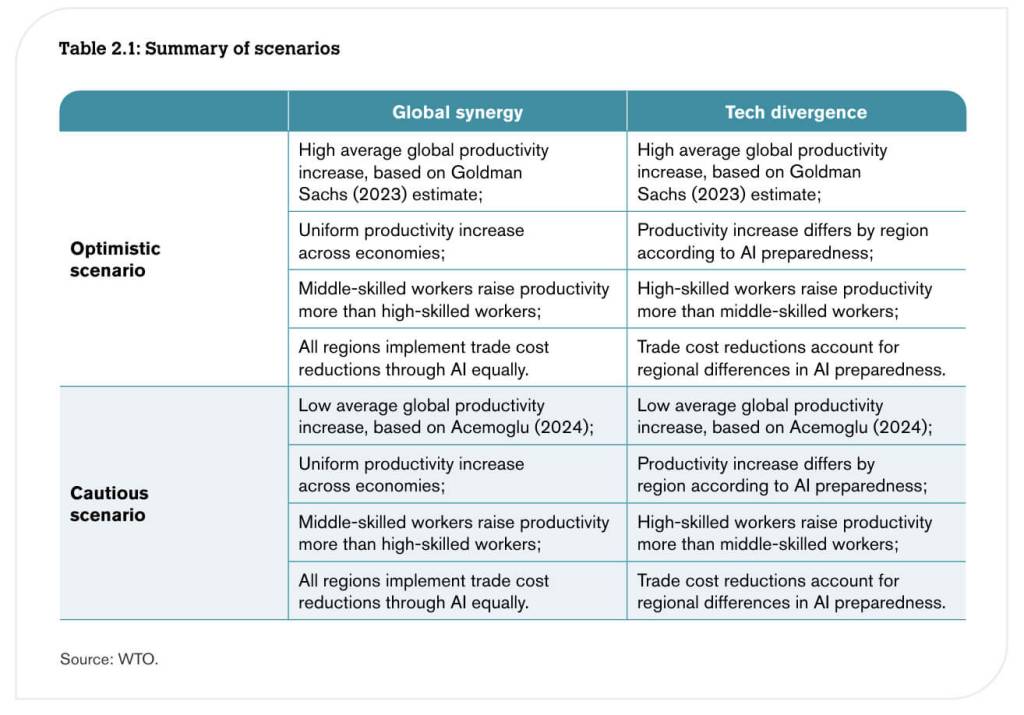

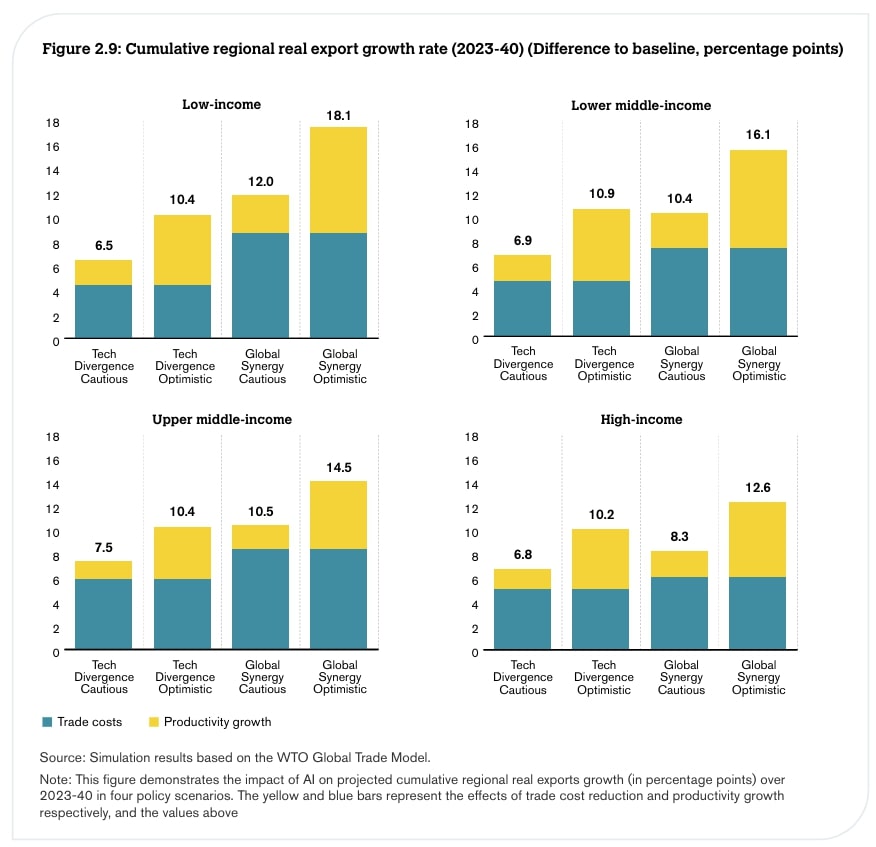

AI’s transformative potential is a double-edged sword, beneficial and detrimental in equal parts. The WTO study simulated four potential scenarios to highlight the role they, similar international organisations, governments, and policy-makers can play in ensuring the most positive outcome possible. The simulation mainly demands coordination.

The results support what has been speculated for some time now: trade growth in high-income countries will be stable pretty much regardless, but the global synergy scenario is essential to bolster trade growth in low-income countries.

Invariably, the report explores how AI will impact trade costs, narrowing this down to three main channels. Improved logistics and diminished compliance costs are well documented, but a third interesting facet is the technology’s potential to eliminate language barriers. By providing real-time translations, AI can significantly reduce communication barriers, supporting smoother negotiations, collaborative processes, and information exchanges. Research indicates that innovative machine translation systems can enhance international trade by approximately 10.9% between participating economies. Its objective nature also overcomes specific cultural differences which guide national trade policy.

Similarly, AI is fundamentally altering global economic landscapes by redefining traditional sources of comparative competitive advantage. Generative AI (GenAI) could potentially add between $2.6 trillion and $4.4 trillion annually, with projected labour productivity growth of around 1.5% per year.

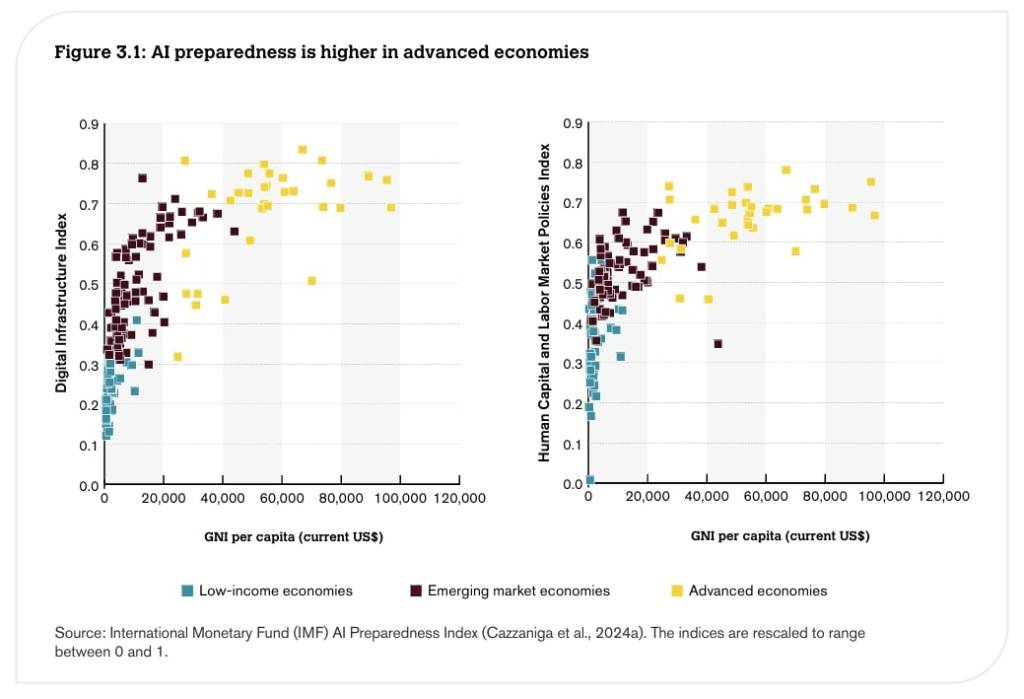

According to the report, the technology offers developing nations opportunities to improve efficiency and access advanced services; yet, its development remains concentrated among large economies and corporations, with substantial upfront investments creating barriers to entry. Emerging comparative advantages will likely depend on factors such as digital infrastructure, human capital, innovation capabilities, and renewable energy potential.

The report hypothesises that nations with abundant renewable energy resources are likely to develop a comparative advantage. AI is very energy-intensive: almost 2% of global energy demand in 2022 came from electricity consumption associated with data centres, cryptocurrency, and AI, a figure set to double by 2026. Countries who can meet this demand could find themselves forerunners for housing data centres and AI infrastructure.

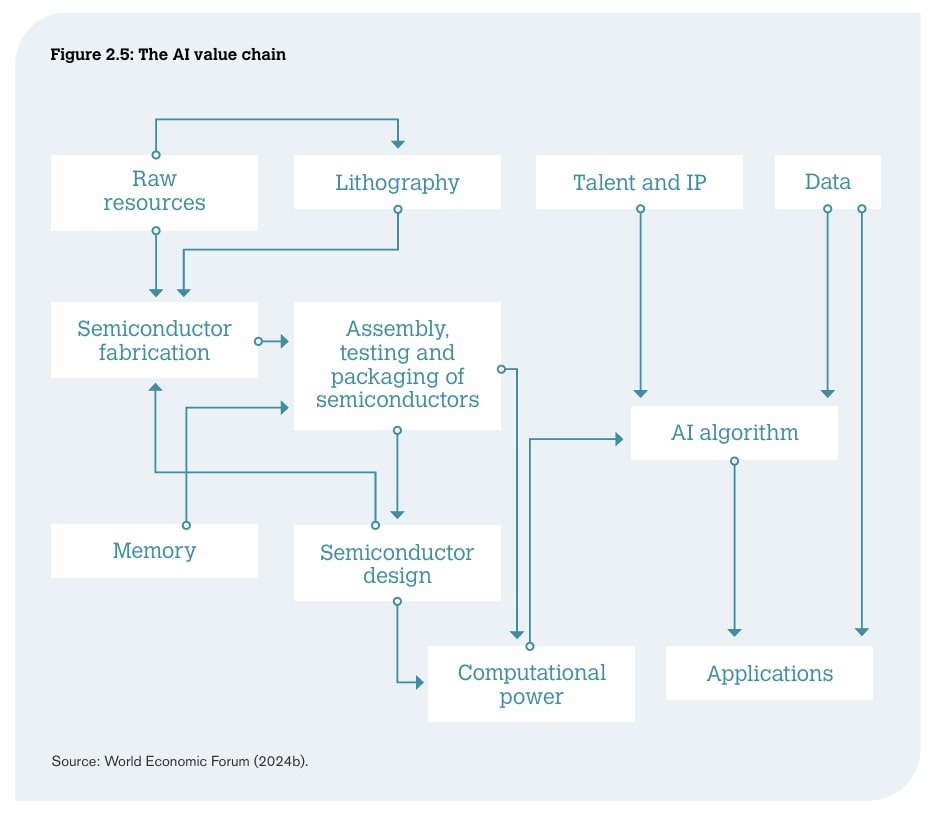

Per the study, the expansion of AI will spur significant demand for complementary technological infrastructure, including specialised ICT services, data management, and computational resources. The global AI chips market, for instance, is projected to grow from $61.5 billion in 2023 to $621 billion by 2032.

Beyond commodities and investments, WTO Director-General Dr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala (quoted in the subheading) often highlights that the future of trade is services. Advancements in AI have transformed how services are not only perceived but also delivered – particularly in intermediate service sectors (B2B rather than B2C, like a US firm hiring an Indian bookkeeper facilitated by tech advancements) requiring improvements to remote work and cross-border collaboration.

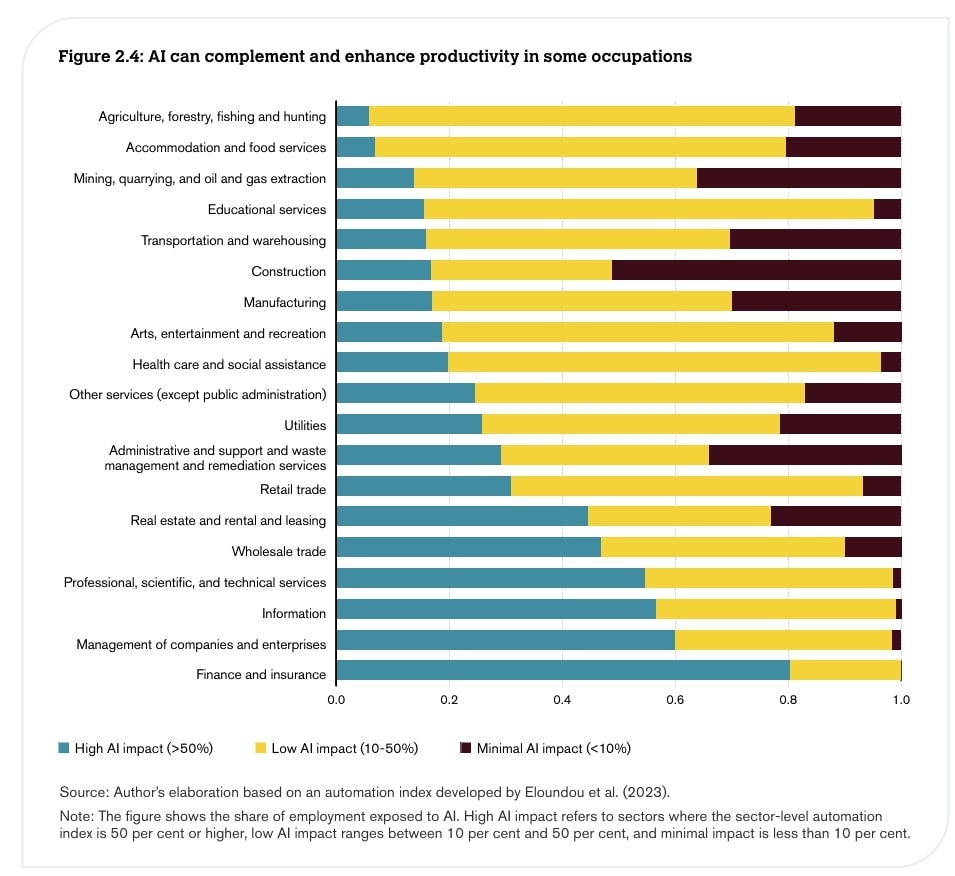

Unlike previous tech advancements, the report positions AI as poised to disrupt white-collar jobs (rather than blue-collar jobs). In terms of economic development, IMF research suggests that AI could endanger 33% of jobs in advanced, 24% in emerging, and 18% in low-income economies. Yet the question remains, are these jobs endangered or will they be augmented?

The technology particularly benefits lower-skilled workers, enabling them to leverage advanced capabilities. The WTO report that GenAI can amplify business consultant performance by up to 40% and increase call centre worker productivity by 14%, with even greater gains for novice workers. Digital tools like machine translation and AI-powered collaboration platforms are making domestic and international workers more interchangeable.

Wider, when GenAI can distil rich-nation services work into an application—something which will be easier for workers with weaker skills who derive the most benefit from ChatGPT—the experience can be democratised among emerging-economy service workers. If they’re using the same GenAI application, will the difference between G7 and emerging-economy services work even be perceptible?

The policy shield

Policy considerations are essential to address the growing AI divide, preventing digital trade barriers while ensuring the trustworthiness of AI to ensure the technology acts to smoothen rather than impede trade.

As of 2023, the investment landscape for AI is dramatically uneven. The United States dominates private AI investment, pouring $67.2 billion into the sector—approximately 8.7 times more than China’s S$7.8 billion and 17.8 times the United Kingdom’s $3.8 billion.

Intellectual property presents another intricate dimension, with questions arising about algorithm protection, data usage in training, and the ownership of AI-generated outputs. AI’s generative capabilities are fundamentally challenging the traditional human-centric approach to IP rights. In short, AI thrives on data, but people value their data privacy.

The demographic makeup of AI professionals is equally misrepresentative. A Stack Overflow survey revealed that 94.24% of data scientists and machine learning experts are male, and predominantly located in Europe and North America. This lack of diversity threatens to perpetuate existing technological and social inequalities. Such inequalities make clear the need for policy to step in, to ensure AI doesn’t become a technology of the privileged few, exacerbating economic inequalities.

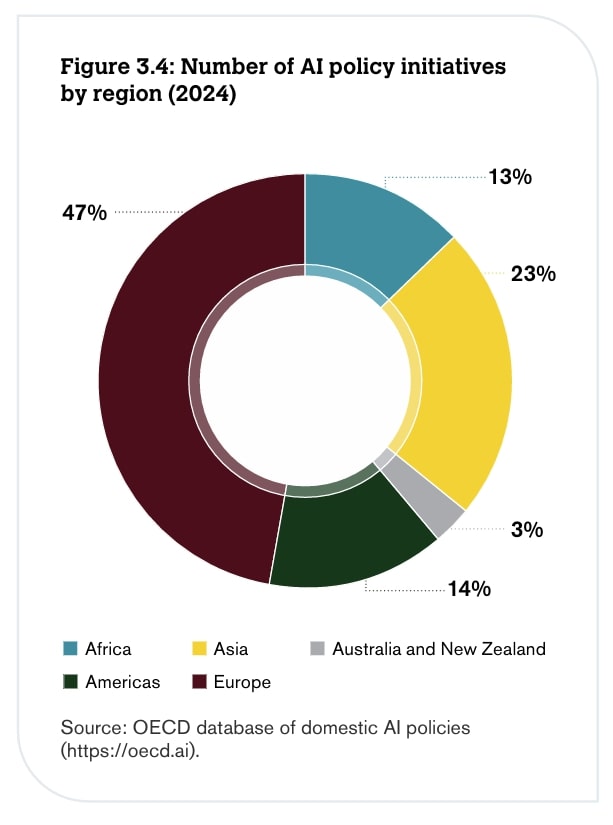

As AI progresses at a breakneck pace, countries are racing to develop a strategy to regulate and promote AI development: 75 countries had an AI strategy in 2023 compared to just three in 2017, and that number is growing rapidly. Regulatory and strategic focus is varied: while the EU promotes safe and trustworthy AI, Singapore’s regulation aims to promote development and make it a regional leader. AI regulation in less-developed countries, however, is lagging behind, with only Uganda having passed any AI policy measures, leading to a technological gap between developed and less-developed countries that will just keep widening.

Regulation on aspects tangential but crucial to AI development, such as data protection and microchip production, also varies between countries and regions, with the EU’s GDPR laws and export protection on AI-critical resources hindering development. International treaties could go a long way in resolving this, but often lack binding commitments that address the fundamental issue of fragmentation.

The WTO’s self-perception

The WTO has combined non-mandatory policy guidance with binding agreements related to AI development. Because of AI’s fast-developing, ever-evolving nature, the WTO has focused on ways to increase transparency and collaboration on new policies. The Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) Agreement, for example, enables members to be notified of new regulations when it is still in the draft stage and submit any feedback, making for a more collaborative and democratic policy process. The TBT Agreement also means that when governments do pass meaningful AI legislation, corporate players have the chance to have a say and, it is hoped, contribute to trade-friendly AI policies.

What is lacking, however, is a substantive, universally respected set of rules on AI development and its application to trade. Many WTO regulations that could fit the bill are stuck in pre-AI days: the Joint Statement Initiative on E-commerce, for example, covers issues crucial to AI like data usage and cybersecurity but has stopped short of including explicit AI provisions despite efforts to reopen discussions and include it. The WTO Customs Valuation Agreement also lacks a specific clause on AI services, which are instead evaluated by cobbling together provisions from different areas of the Agreement, making for an opaque and non-uniform policy environment.

Binding commitments, when they exist, are tangential to AI rather than directly affecting AI on trade: 40% of WTO members have not made any commitments to computer services at all; the ones that have contain no mention of AI, instead limiting themselves to ICT services only—which are important for AI development but by no means the whole story.

Other agreements, like the Information Technology Agreement, the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Agreement, and the non-discrimination principle, contribute to an environment that is friendly to trading in AI products but stops short of directly affecting or regulating them.

When concrete regulation is lacking, the WTO’s role in AI trade regulation is perhaps greatest in the soft power realm. Trust in institutions is declining globally, and people, countries, and corporations alike must first become comfortable with AI before the technology can be put to any real use. By bringing experts and governments together and mediating between conflicting parties, the WTO can build what Daniel Trefler of the Rotman School of Management described as a “global chain of trust” that is crucial to long-term sustainable AI development.

—

James Manyika, a senior Google executive and UN AI advisor, argues that AI could contribute to 79% of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals—a remarkable potential given that the world is currently on track to meet only 15% of these goals.

This report synthesises a year’s worth of observations and commentary on the pace of AI, and will be useful when it comes to drafting a policy on how the technology can best democratise trade.

Going forward, innovation will likely continue to come from the private sector, which is mandated to create value for the shareholders. But international organisations like the WTO must look for the public good, and balance these profit mechanisms to ensure AI makes trade less divisive and obstructed.