On the 24th May, Credit rating giants Moody’s lowered China’s sovereign debt rating to A1 from Aa3, which takes the economy from “High-Grade” to “Upper-Medium Grade” investment specification. This downgrade is a result of continuous slow growth, and an increase in debt economy-wide.

What China’s Credit Downgrade means

Credit rating agencies such as Moody’s provide the global investor community with information on an institution or country’s ability to pay back debt. Many things are considered and analysed, and the institution or country is awarded a rating. The scale shows AAA as the best rating – a rating held by countries such as Australia, Canada and Denmark. The worst ‘junk’ rating is awarded when an economy defaults on its debt – such as South Africa’s rating of BB+, a “non-investment” grade rating.

The lower a country’s credit rating, the more expensive it is for them to borrow money – as It is seen as more of a risk for the lender, so the risk is cushioned by the increased interest.

Slow growth

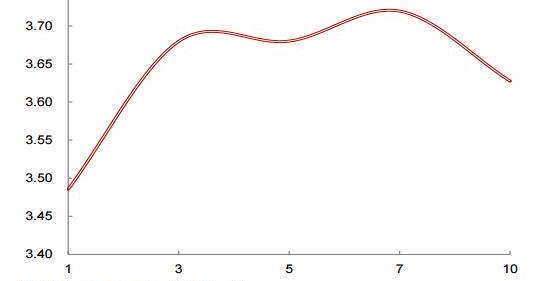

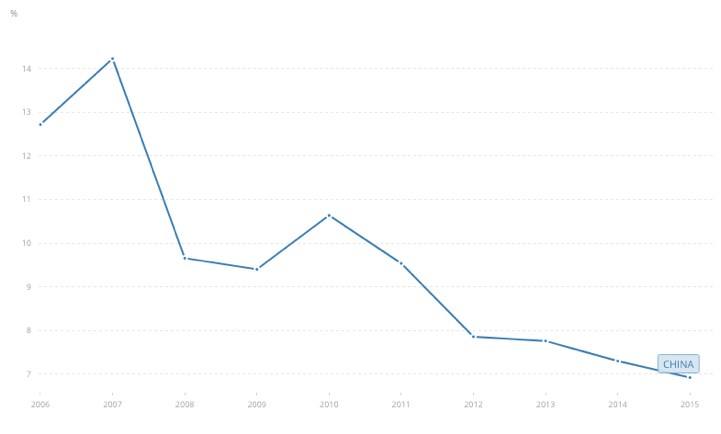

Moody’s announced the downgrade alongside reasoning of China’s slow growth and increasing debt economy-wide. The growth rate experienced by China over the last 8 years has shown a strong downward trend.

- Source: WorldBank.org

As shown above, excluding an increase of 1.236% over 2009, the growth of Chinese GDP has declined from 10.636% in 2010, to 6.918% in 2015, 6.7% in 2016, and 6.9% in the first quarter of 2017. This is in contrast to their pre-2007 growth rate of 13-14%.

This decline in GDP growth means the economy is slowing, and for any country this would be unsettling, as it is not uncommon for other economic downturns to follow a decline in growth. For example, If the economy is tightening, and growth is slowing, the chances of Unemployment rising are likely, and the consequences of this are clear. However, in China’s case, their unemployment rate has hovered around the low 4%’s due to the fact they are an industrial exporting country.

The reasons for China’s decline in growth are widely debated, however many will agree this was inevitable. This is purely because between 1998 and 2007, they averaged 9.99% GDP growth, and the bigger a country/ business gets, the harder it is to keep growing.

Movements in growth stem from changes in an Economy’s workforce, capital or productivity, or all three in China’s case throughout many years. When these three variables all increase at a strong rate, the result is rapid economic growth. However, these factors can only develop at a certain rate for so long, and naturally begin to slow. This results in the aforementioned growth slowing down also.

Rising debt

More interestingly, the decline in growth rate becomes increasingly concerning when the debt-to-GDP ratio is as high as it is in China.

Exiting the global crash of ‘07/08’, China fuelled their recovery and growth through excessive credit aid. At the end of 2016, China’s debt to GDP ratio rose to 277%, up from the previous year of 254%. This is in contrast to the United States ratio of 108.25%, the French ratio of 97.15%, or the Spanish ratio of 100.08%.

Also note the economic position of Greece, who are facing a debt crisis with a debt-to-gdp ratio of 177% – however the relative size of the economy’s and populations explain the difference in economic situation. For more information on the Greek debt and how they approached recovery, see Trade Finance’s – “Greece Debt Talks”.

When countries finance their economy through excessive borrowing, it is not always bad. For example, Germany received large financial aid after the Second World War, which enabled their economy to grow again and allowed the German’s to repay these debts once their infrastructure and industries rebuilt.

The issue for China, is their growth is not showing signs of enabling China to repay these debts. Because, previous to the last decade showed exemplary growth, the level of borrowing increased with it.

Furthermore, it is not just the government’s debt that is of worry for investors world-wide. Household debt to GDP rates have been on the rise since 2008, where the household debt amounted to 17.86% of GDP. By the end of 2016, it had risen to 44.83% of GDP.

The uncertainty surrounding the Chinese future ability to repay debts is seen in their Nominal growth rate (which is the sum of real output and inflation), which fell from 15% in early 2000’s, to 8.5% now. This essentially means that debtors are more likely to face challenges paying their bills and thus defaulting on payments.

“Social Capital”

An interesting type of infrastructure funding has increased in popularity in Chinese provinces in recent years. The Industrial fund, or Social Capital as the Chinese Government call it. With traditional infrastructure funding, the local government would contact banks for project funding, alongside their own investment.

However, the Industrial funds allows the city and banks to pool their investment together as before and will then be assigned a project/ contract. Once this has been established, the fund is open to the general public investment.

China’s spend on Infrastructure has been enormous, and they “spend more than the United States and Europe combined”, according to Bloomberg. And it had been paying off, with millions of jobs created through infrastructure spending, and the demand for goods like cement contributing toward this also.

We have also seen China’s transport facilities advance significantly, with Airports, Railways and roads/ bridges increasing in number and quality. This has promoted business and made the standard of living generally higher for the Chinese population.

Unfortunately, this large infrastructure spend was justified through continuous, strong economic growth. As discussed, this was the case for China for many years, however with growth now slowing, and consumer debt rising significantly, Moody’s Ratings decided the risk around the Chinese economy had increased.

So, what is the concern?

In one word, complacency. Because the state is willing to bail out in times of need, many will feel the problem is not as bad. The Chinese government first started approaching the debt issue in 2010, since then they have taken few serious measures. However, with the credit rating falling, this is likely to increase the cost of loaning.

For more information on how this will affect Chinese investment patterns, see Trade Finance’s Article – “Is China Stopping Overseas Investment?”

So, What now for China?

Politically, this has not come at a good time for the leading communist party, who are approaching their largest leadership meeting in which they will want to project China and President Xi Jinping as strong.

Economically, the initial response was a drop in both the Yuan and the majority of major stock indexes. The fall in ratings will mean international borrowing will become more expensive, which will lower the amount borrowed.

However, China’s government does not seem phased, as their Finance Ministry responded to Moody’s rating drop as being based on “inappropriate methodology”, and that it is false.

Accurate or “inappropriate”, the downgrade will affect the Chinese economy, which will then impact the world economy. However, it is the way in which the Chinese respond, and behave moving forward that will determine the outcome. Follow Trade Finance Global for updates on the Chinese economy.