Welcome to the monthly TFG & ICC DSI Column! Check back here at the end of every month to hear from Pamela Mar, Managing Director, ICC Digital Standards Initiative (ICC DSI) and get the latest insights into digital trade!

January| Trendspotting technologies for trade in 2025

The Western media is abuzz about DeepSeek. Its release on January 20 triggered a massive stock rout of key technology stocks including Nvidia, which lost $600 billion in market cap in a single day. Since then, any number of Western tech watchers have alternatively decried the threat to American technology leadership while trying to poke holes in DeepSeek to “prove” that it is not as good as it seems.

The appearance of DeepSeek should not have been a surprise for anyone following the growth of artificial intelligence (AI) and its entry into many facets of daily life, industry and the arts. And yet even as we prognosticate about the potential applications of AI, we would do well to remember that while many technologies have huge transformative potential, their eventual trajectories depend very much on humans’ ability to bridge the gap between theory and practice.

The Gartner hype cycle, while simplistic, has gained a following because it reflects well some realities. Robotics was predicted to end factories and assembly line workers as we know them, and 3D printing was supposed to eliminate retail (because everyone would just print what they needed at home instead of buying it at the store). Blockchain endured a similar hype, where it was touted as the technology to end supply chain management with secure smart contracting taking over each node in the production cycle. Today Web3 and crypto enthusiasts give us their version of the future, whether it is the end of money or the end of man.

Of course, every technology makes its inroads, and great discoveries are made in the process of pilot and operationalization. Injecting new tools into old processes is a time-tested way to ensure continuous improvement, or kaizen. On the other hand, the gap between the potential represented by technologies, and what happens in practice, remains very wide for supply chains.

The issue is not so much that the technology is not relevant, but rather that supply chains are highly complex. What works for one player might not work for others on the chain, driven by differences in standards, capabilities, approaches, or other factors. The digital standards initiative (DSI) and others aim to solve the standards part of this problem, so that differences in data or process standards will no longer prevent supply chain partners from adopting and benefitting from digital technologies.

But there are a wealth of other challenges to address: habits die hard and national rules and resources vary widely, producing differences in how parties within different jurisdictions operate, even as they decry the inefficiencies and costs that result from dated approaches.

So yes, we should recognise the potential of AI—indeed, prepare ourselves by learning fast, imaging the AI-laced future, and experimenting with its possible applications—but continue to devote the bulk of energy to operationalising the wealth of technologies that may not be as headline-grabbing as DeepSeek, but have been proven in on-the-ground operations. Importantly, also, ones which are cost-effective and well-serviced.

Which technologies have the potential to bridge the potential/practice gap and thereby scale widely in 2025? It’s anyone’s guess, but blockchain and cloud are on top of my list.

It’s been possible to securely transfer data and records between parties on blockchain, for years—the WTO’s seminal paper on blockchain in trade, by Ganne and Patel was published over five years ago already—but doubts about the efficiency of public blockchains and questions about data portability with private blockchains have prevented widespread scaling. Today, these questions have been answered by aligning standards across platforms and allowing data to flow securely not only within a platform but across networks.

This opens real possibilities for two applications: digital trade finance and electronic bill of lading (eBL), both of which depend on portability across multiple users and networks. The seeds of this are evident in the recent FIT Alliance eBL survey, which showed a marked rise in adoption of EBL amongst users: from 32.5% two years ago to 49.2% in 2024. Most users continue to use both paper and EBL, but as more customers realize the benefits, that figure will rise. This is seen in the over 70% of users who plan to begin using EBL in the next two years.

As for digitalising trade finance, to drive efficiency, lower costs, and scalability across underserved populations: one of the major issues was always the validity and credibility of documentation provided by the borrowers. Today, secure documents, or electronic records, can be transferred, traced, and validated through blockchain-secured networks, thus providing data that can be intelligently ingested by banks; that is, if we align standards and find the tools to enable that smart transfer. Watch this space for the launch of the ICC Banking Commission and DSI’s dataset work building on our Key Trade Documents and Data Elements framework, which will take place in February after a year’s work involving over 30 banks and financial services experts…

Admittedly, blockchain and cloud are not new, and the sector has already had a few shakeouts. But the level of industry knowledge and experience with blockchain-based transfer has been growing all this time. Finally, it feels like the trade has matured, and with increasing usage, costs have declined, which is always a good thing in emerging markets.

And for anyone looking for further evidence, China has been pursuing blockchain-based eBL adoption for well over a year. The Fit Alliance survey shows China-based adoption rates running significantly higher than other regions; anecdotally, China adoption of eBL could be as high as double that of other areas of the world. The government has played a significant role: supporting pilots, training public sector officials, and driving adoption and engagement via ports and other key nodes. The recent maritime regulation completes this stage of the picture.

Given the increasingly oppositional narrative around DeepSeek and China’s AI capabilities, one should also be reminded that China’s progress in driving eBL adoption is not mutually exclusive. The Singapore-China story is a testament to the fact that parties in the digital trade world work with and rely on each other to learn and jointly progress. We should keep expanding the circle.

In short, today’s headlines are all about DeepSeek and AI, and certainly, we should keep an eye on that. But we should also remember to keep a second, watchful eye on the many technologies that appeared years ago and are finally coming into being as practical tools that are easy to adopt by very different parties. They will be the ones to bridge potential and practice and really drive change on the ground.

November | Tracking digital trade in Peru and beyond

November 2024 has turned into a remarkable month for those working on international trade in Peru, with three major steps forward.

First, the country successfully hosted the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) series of meetings, ensuring a focus on supply chain connectivity, digitalisation of cross-border trade and deeper integration of trade and sustainability portfolios. With strong input from Singapore and Australia on digital trade, as well as robust evidence of the benefits potentially awaiting those with higher levels of trade connectivity, the insertion of these elements into the 2024 Machu Pichu declaration might have been a foregone conclusion.

Nonetheless, in a year of geopolitical unpredictability – with the US presidential election taking place just ten days before the APEC leaders summit – a strong statement for multilateralism takes on added significance.

Secondly, a separate announcement confirmed Peru’s accession process to the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA), coming one and half years after its formal request. By signing up for DEPA, Peru is implicitly committing itself to global rules meant to encourage digital trade and the digital economy wherever possible, while protecting and promoting cross-border data flows. The commitment is good news for progressive voices within government and industry who see or hear of the world’s trade and supply chains going digital and see that a similar transformation at home could create economic expansion.

Thirdly, the opening of Peru’s new Chancay port has been heralded as a harbinger of a new era. Notably, the port is fully automated, using robots and autonomous vehicles connected within a full digital twin. As a deep sea port, it can handle the largest container ships, and is positioned to cut China to Peru transport times by a third from 35 days at present to 23 days when fully operational. Logistics costs are also projected to decline by 20%.

Although most observers have focused on its geopolitical significance – given that it was built and will be operated by the Chinese state-owned shipping company, Cosco—it holds great potential to accelerate the shift to digital, not just in Peru but also within the Pacific Alliance.

Today China is among the top trading partners to several key countries along South America’s Pacific coast. It became Peru’s largest trading partner in 2013, with two-way trade of over $35 billion in the first ten months of the year, a figure which has grown by 14.6% since 2016. So, it might make sense from the Chinese side to invest in a port in Peru, given strong local ties and rising trade with natural resource rich members of the Pacific Alliance, which includes Chile, Mexico, and Colombia in addition to Peru.

But the port could also be an accelerator of digitalisation in Peru if it becomes a site for demonstrating the benefits of digital border operations, and technology transfer within regional supply chains. Working with the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), South American countries have all been developing trade single windows, but in a number of cases, full integration with port operations has yet to take place. Could Chancay be the game changer given that it is already digital and no new data and infrastructure conversion needs to take place?

Another possibility is that the port becomes the front line for digitalising the transhipment process along the Pacific Coast. This would reduce the time and costs of transhipment, thus making more affordable trading partners which were hitherto out of reach (cost-wise). Trade diversification could buttress Peru’s trade profile both in terms of the mix and the process.

Much has been made of the 8,000 jobs to be created by the port’s full operation. There is the prospect not only of new professional training for the local logistics industry but also of new digital services connected to the port and the trade financing process. In this way, the port could drive overall supply chain upgrading by “leaking out” digital skills into the community, and in time, fostering innovation ecosystems around the digital supply chain.

In most countries, digitalising cross-border trade takes time. Only after covering legal reform, popularising digital trade standards, and rolling out pilots within business and industry, can widescale adoption and education follow. As a result, accelerators are valuable. COVID was one such accelerator, providing many with paperless, virtual transactions that could substitute for, and even improve high-touch and manual processes. New technologies, such as AI, could also enable breakthroughs in interoperability, risk mitigation, and rapid processing at scale. It is tempting to think that Chancay is well-positioned to be Peru’s digital accelerator.

Of course, much depends on the implementation of APEC statements, the progress of its DEPA negotiations, and as well, the road to getting the port to live up to its promise. It looks like interesting times ahead for Peru’s digital agenda.

October | Three steps ahead on the road to interoperability

Sibos 2024 was not the first time that ‘interoperability’ figured prominently among the buzzwords – but 2024 was perhaps the first year where the talk was about implementing or scaling solutions to deliver interoperability rather than a general exhaustion that the holy grail still seemed quite far off.

Three pieces of progress featured at Sibos now make it clear what an interoperable future might look like. The first, obviously, is the reality around ISO 20022 implementation as the adoption deadline of 2025 approaches. Sibos 2024 featured a flurry of banks calling for faster adoption and for resources to support developing country banks, showing that even if the adoption rate of 26% appears “low”, the industry momentum is clear.

Moreover, this is no longer about ISO 20022 as an exclusionary choice, but rather as an option that can both facilitate interbank services and services across the whole trade chain. This has recently been demonstrated by Swift’s interoperability pilot where an EBL was transferred between players using the Swift network. Moreover, with Cross Border Interbank Payments System (CIPS) joining the Swift network, and given the participation of CIPS across key interbank workstreams globally, perhaps the conversation can move away from the geopolitics of US/China or dollar/renminbi, and focus on how these two networks will work together to expand the market reach of all players.

The second piece of progress is around digital identity, where the legal entity identifier (LEI) has gained irreversible traction as the universal connector to achieve interoperability across entities regardless of size, location, sector, or specificity. This is especially important for digitalizing trade given that one-quarter of the core data elements required to operationalise data sharing across global supply chains are in fact entity identification: think buyer, shipper, seller, and the like.

And eventually, every digital supply chain will need a robust way to tag data as being generated, shared or received by entities along the supply chain. Without a “tag” that transparently identifies entities and their associated data, the vision of data sharing and the efficiencies it generates will be very hard to accomplish.

Until now, the LEI has faced issues related to scale and accessibility. Created to expand financial inclusion, particularly amongst small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and emerging markets, many of the holders of the 2.5 million LEIs issued worldwide are large companies such as banks and multinational corporations (MNCs) in developed markets. Given that there are roughly 330 million enterprises worldwide, and notwithstanding the fact that many of them are not directly participating in global trade (though that is also part of the problem) there have been assumptions that the LEI was not achieving sufficient scale or penetration.

The more nuanced view is that the absolute number of LEIs directly issued might be less important than the evolution of the LEI into a connector of national identity systems, and a platform for innovators to deliver services such as financing to trade participants, with the LEI as an anchor. The LEI’s imporance to trade can also be seen in the fact that the fastest growing LEI jurisdictions in Q3 2024 are those which are taking visible steps to advance their digital trade agendas.

This includes New Zealand, a founding member of the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement; Australia, which recently announced its commitment to align to the Model Law on Electronic Transferable Records (MLETR) by June 2026; India, which is accelerating aspects of digital finance; and Thailand, which is in the final stages of aligning to MLETR under the guidance of the Electronic Transactions Development Authority.

In short, these two steps forward are both solutions for interoperability, demonstrating that the more we can reimagine what interoperability looks like – that it need not be an either/or choice – the more rapidly we will accomplish the connections which allow data to flow in ways that create serious insight and efficiency.

The third step relates to the governance principles of data sharing under interoperable frameworks, notwithstanding that each framework will have its own protocols and principles for data management, transfer and sharing. For corporate users, who might be using multiple frameworks or service providers, the variety of protocols and principles could present difficulties particularly if data and electronic records need to be treated in specific ways. It would be easier, and more scalable for the industry as a whole for, users to navigate one set of requirements, and even more so if there are legal requirements implicated as they are in the implementation of MLETR.

To fill this gap, the International Chamber of Commerce Digital Standards Initiative (ICC DSI) and the Digital Governance Council recently developed a technical framework that interprets reliability for commercial enterprises such as trade platforms. The framework offers a standardised way for enterprises to assert or attest to their reliability under these conditions, thus saving potential customers the burden of making this assessment on their own and possibly without the required expertise. This should be seen as one more piece contributing to solving the puzzle of interoperability, and digital trust, at scale.

The cliché goes, “two steps forward and one step back”. After years of searching for the ‘solution’ to interoperability, and having many steps back as possible solutions fall short, we should welcome the opportunity to see these three steps as good momentum on the road to trust at scale, for the evolving digital trade ecosystem.

September | Complexity and opportunity on the road to digital trade

Everyone loves a good number. And in digital trade discourse, the bigger the better:

- $6.5 billion in efficiency gains for shippers from adopting electronic bills of lading globally.

- $90 billion in potential trade gains across the 54 Commonwealth economies from digital trade

- $1 trillion in the potential expansion of the digital economy from the implementation of the Digital Economy Framework Agreement in the ten ASEAN nations alone

Paired with the inclusive trade agenda, these numbers make for powerful references. They assume that a significant amount of the expected gains will trickle down to the small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), who bear the brunt of the two gaps: the trade finance gap ($2.5 trillion, according to this year’s ADB report), and the opportunity gap, which is not yet a stylised trade term but perhaps should be.

To me, the opportunity gap refers to the difference between SMEs’ capacity to participate in international trade, and their actual participation rate. Though SMEs account for the majority of enterprises and jobs in many countries whether developed or developing, they may account for just 20% of exports across, for instance, the Asia Pacific.

Large firms have a much greater propensity to export, sometimes more than double that of SMEs. They are also more diversified, exporting on average to seven countries versus SMEs exporting on average to only 2.5. The list of unrealised potential could go on.

Digitalisation is often cited as a solution to drive SME inclusion and to close the trade finance gap. One of the three themes of the recently concluded WTO Public Forum was ‘Digitalisation as a catalyst for inclusive trade’, with over 20 sessions focusing on various aspects of the topic. Evidently, the theoretical case is strong, and at least at the level of pilots and funded programs there has been some success to bridge gaps. Additionally, the rise of e-commerce has accelerated the participation of SMEs into international trade, even in the absence of major policy interventions in this direction.

Yet the trade finance gap persists at high levels despite the post-COVID recovery, as does the SME finance gap which represents SMEs’ “unmet financing needs” at $5 trillion. If we are making headway, we are not doing so fast enough.

The answer may lie in stepping away from “big numbers” and into the shoes of an actual SME. During the Public Forum one participant who had spent many years working with SMEs in emerging markets suggested that when SMEs are asked about barriers to trade, their chief challenge is “finding the buyer.” This aligns with other surveys of SMEs who trade globally, where the chief obstacles they cite are customs procedures, logistics, and foreign currency issues.

Today, it is estimated that roughly two-thirds of all manufactured goods trade takes place in global value chains. While global value chains have been a key vehicle enabling developing countries to drive jobs and growth, they have become increasingly complex, sometimes with 20-30 parties processing 100 to 200 documents covering a range of services that go towards the delivery of the good to the buyer.

The complexity puts any small player at a disadvantage, and this is magnified as buyers choose their own digitalisation pace, platforms, and processes. To this, we add differences in rules and procedures across borders, and tariffs and non-tariff barriers. It’s a wonder that SMEs manage to export at all.

One takeaway from the WTO Public Forum is that we will not solve the inclusion gap without addressing the complexity problem. Customs single windows are a good start as they simplify the business-to-government (B2G) clearance process. Assistance should be given to countries that have yet to complete their single windows, with guidance towards a globally harmonised dataset.

Business-to-business (B2B) transactions along the supply chain merit the same treatment: with 21 of the 36 key trade documents already digitalised in globally interoperable formats, with another six en route to completion, we need a global campaign to drive digitalisation across the entire chain. By integrating B2B and B2G processes through their core data, we move towards a conceptual single window across the entire supply chain, riding on one data set and one single source of truth. This will vastly simplify and streamline processes that drive supply chains while creating traceable records that will help with border clearance and trust across the chain.

Technology will be key to this vision, and yet, as Alisa Dicaprio recently reminded us, we should be careful not to sit back and wait for it to address inclusion as a matter of course. The right policies will be paramount, not so much where markets are functional but to promote digitalisation that changes the way trade operates and shares the spoils of growth.

Some good starting points would be to enable any enterprise to trade digitally, by opening up the use of electronic (transferable) records in trade and to nudge the various movements towards universal electronic invoicing, electronic transport documents (like eBL), and electronic product declarations.

Policy can help slow the slide towards digital islands – primarily the reserve of the large and well-resourced – and recentre the trade world on our work to delayer, simplify, and connect. The opportunity gap will probably be around for some time longer, but at least we do have the tools to make sure its days are numbered.

August | How can APEC deliver tangible gains for digital trade?

Reflections coming out of the APEC SOM3

Not many places in the international community are still safe zones for free trade advocates. And yet, APEC, or the Asia-Pacific Economic Community, continues to hold fast to its aim to build a free, open and transparent trade and investment community as part of its Putrajaya Vision 2040 – even as the cause of free trade comes under fire globally.

APEC has always been about what economies can do together in collaboration, rather than the many reasons for which they may stand apart. Geopolitics aside, growth through trade has remained an attractive proposition for APEC’s 21 economies, which account for 2.9 billion people and 60% of global GDP. At the same time, the sheer diversity within the APEC grouping – including members on opposite sides of the planet, and where the richest has a GDP per capita that is over 27 times the poorest – means that progress measured in a strictly linear sense cannot be the only objective.

Luckily, trade digitalisation is definitely on the APEC agenda. The recent Senior Officials Meeting in Lima, Peru, involved numerous sessions and seminars on the subject, plus an entire digital week. But anyone looking for announcements of commitments, plans, and implementation agendas may be left waiting.

Digitalising trade is only partially about policy and legal reform. Yes, aligning to MLETR is foundational, and necessary to enable digital trade at scale, but it is only one of the building blocks to realising transformational change. MLETR must be accompanied by deep education and engagement across the public and private sectors on standards, trust, and interoperability to even begin the journey towards a harmonised, inclusive digital trade ecosystem.

One only has to examine the 10 economies (or 12 if one counts Germany and the USA) which have officially aligned to the MLETR, to understand that legal reform does not trigger a tidal wave towards digitalisation. The UK for instance, did experience a number of “day one” pilots that were timed to take advantage of the Electronic Trade Documents Act introduced in September 2023. But beyond this, transformation takes time. The single window is still coming into full function; companies grapple with standards; parties are still asking when the market will move.

In this regard, APEC can play an important catalysing role by providing tools and training, facilitating the sharing of best practices, and enabling economy-to-economy exchange and technical assistance to be more effectively delivered: not by relying on iron-clad commitments to policies. It’s no wonder that when long-time APEC participants are asked what it does best, they frequently cite ‘information exchange’ first. This may sound a bit wishy-washy, but for digital trade, it’s essential at this elementary stage where governments and policymakers are eager to get the technical, legal, and practical education they need to move agenda in their respective environments.

In this regard, it’s high time we move from well-heard mantras on why digital trade is good – for business, finance, MSMEs, and growth – to addressing the “how”. The MLETR implementation journey has eight steps, including tailored tools, gap analyses, and technical assistance; beyond this, governments can take seven more critical actions to create an enabling environment for digital trade. These include incentivising and supporting training to boost digital IQ and digitalisation capacity in the private sector, particularly amongst SMEs; building out digital public infrastructure including interoperable digital identity; fostering an ecosystem where startups, innovators, and digital services providers can thrive; and popularising interoperable digital standards, and others.

Many of these can be delivered through a core set of tools that can be a modular menu for individual economies to draw on to meet their specific needs. An APEC digital trade toolkit could help accelerate the current approach where economies may struggle, or perhaps overpay, to find resources and expertise tailored to their stage of development. The toolkit avoids a situation where everyone has to start from scratch and make the same beginner’s mistakes.

Lastly, Apec has an ideal set-up to drive change in digital trade– given its cycle of meetings, the engagement of business through the APEC Business Advisory Council, and mechanisms to channel resources towards agreed agendas. By taking a unified approach, APEC could give a shot of energy to the international digital trade movement, particularly in Latin America where digital trade is crucial to deliver growth once again. In doing so, APEC would boost its own credibility and that of free trade.

July | Global adoption of MLETR: Are we approaching the turning point for digital trade?

The Model Law on Electronic Transferable Records (MLETR) has become a rallying point for digital trade advocacy. It provides the foundational framework for moving from “document to data” by enabling the use of electronic transferable records in the place of negotiable documents in trade.

There are only seven so-called documents of title which are directly covered by MLETR (and much depends on which ones each country will incorporate) but the law has nonetheless become shorthand for revamping paper-based trade systems into digital ones.

It is also central for educating policymakers about the gains from digitalisation and how to access those, and for pushing the private sector to embrace digitalisation all along the supply chain.

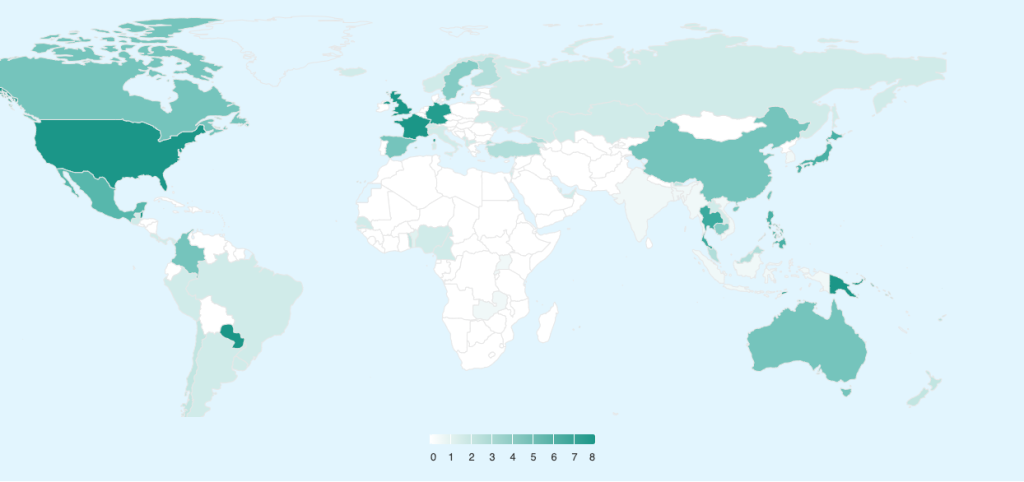

Seven years and one week after MLETR was finalised by the UN Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL), ten economies have adopted it officially into their respective legal systems, with another two, Germany and the USA, having effectively aligned, for a total of 12.

Source: https://www.digitalizetrade.org/mletr

With 188 members and observers participating in global trade via the World Trade Organization (WTO), twelve in seven years might seem underwhelming, but it is far from the case.

12 use cases for MLETR on the global stage

A closer look at the twelve adopters, as well as the longer tail of those economies that are actively in preparations, offers a glimpse into the potential of MLETR to transform global trade.

The MLETR framework is both simple and robust, and therefore adaptable across developing economies seeking to leapfrog ahead in their digitalisation journey, as well as highly developed economies with more complex trade profiles.

Of the twelve adopters, five fall into this latter category—Singapore, US, Germany, UK and now France – which together make up nearly 37% of global GDP.

The remaining seven adopters are mostly smaller less developed economies with a collective impact of just between 1 and 2% of global GDP.

Conventional wisdom is that supply chains operate at the technological level of the least developed player, so perhaps with “only” 37%” of global GDP aligned to MLETR, it might not be a surprise that use of electronic documents such as the electronic bills of lading is still estimated at less than 5%.

It’s true that some processes, for instance, the customs declaration which benefits from coordination under the World Customs Organization, or the payment confirmation under SWIFT are highly digitalised; but overall progress on digitalising most other trade documents is still rather halting.

What is slowing the digitalisation progress?

The reasons for this are well known: developed countries have legacy systems and their own approaches while developing countries need capacity building, new hardware, and massive resources to bring them within reach of digital trade.

Everyone hides behind business as usual, cumbersome as it may be.

I would argue that we are just now reaching a crest of change, and that 2024 will go down as a historic turning point.

Interest in digital trade is stronger than ever, and political will is emerging, with resources falling into place. Looking at economies that are actively working to comply with MLETR, we assess their readiness based on existing legislation, roadmaps, and access to technical assistance.

Our findings show that both large economies, such as China and Japan, as well as smaller ones, including Thailand, Morocco, and Colombia, are making these preparations.

In sum, economies that fall into stages 2 through 5 on the MLETR Tracker, signallling active preparations, account for roughly 26% of global GDP. Adding these economies to those who have already aligned would mean over two thirds of global GDP would be aligned to a common framework for digitalising trade.

In other words, the crest of the movement is view.

What can we do to make it arrive faster?

Although MLETR itself appears to be one size fits all, its adoption is anything but. From the actual legislation to the implementation across governments, there is no simple answer.

The MLETR tracker lists eight steps to legislation passage, including the preparation of an impact study and roadmap, and education and engagement across different parts of the government. But even these are subject to variances given the individual characteristics of economies and governments.

Questions from roundtables conducted in the last two months highlight the broad spectrum of issues that need to be addressed:

- If we are planning to move towards automated clearance and checking, what happens to the current occupants of those jobs?

- How should digital trade platforms to transfer ETRs work with existing digital solutions being used, particularly in the financial sector?

- Will individual bilateral arrangements be needed in every instance?

- Should the government just develop a single platform to ensure the implementation of reliable, interoperable systems?

- How should we ensure that our ETRs won’t be subject to attack, a question amplified given the recent Cloudstrike outage.

The only commonality across these issues is that they will require new levels of collaboration between the public and private sectors; in turn, faster progress can also arrive with key domestic players drawing on the wide range of international experiences available.

Chambers and industry associations will be crucial to disseminating new best ways of working, training the needed new skills, pinpointing bottlenecks, and sharing progress to empower more to act.

And while every country is unique and will chart its best path, the international community can highlight all the options available and channel development assistance.

At the same time, digital trade corridors can offer opportunities to practice these skills even before legislation officially passes, as is happening now with China and its trading partners.

As more economies come online to digital trade, that menu of experiences will increase, and this can only spur faster integration of good practices from abroad. In other words: practice early, and communicate widely.

Digitalising global trade is a journey, and the passage of legislation is but an early step. The combination of legal and technical expertise, capacity building, development aid, and political will that will enable faster implementation of MLETR Is now clear.

Given the rewards, now is the time to marshall these resources to bring more economies over the finish line—or starting line—sooner, so that more people can benefit.

June: What can Artificial Intelligence do for Digital Trade?

The Key Trade Documents and Data Elements (KTDDE) analysis of the ICC Digital Standards Initiative proposes a “framework for digitalizing the entire supply chain” using “targeted recommendations to accelerate …the digital transformation of all associated processes.”

The word choice was deliberate. The recommended standards to align electronic documents and key data elements across the supply chain would, when implemented, enable connectivity and interoperability across the many parties who might rely on such data for commercial, compliance, or other needs.

Challenges in implementing digitalisation

The key is “when implemented.” KTDDE provides a framework for understanding how trade data and documents could be interoperable, and thus facilitate data sharing and traceability. However, currently, there is a wide gulf between the framework vision and its implementation.

There are legal and regulatory issues, financing needs, and capacity gaps, but even when these are peeled away through stakeholder efforts, there remain significant technical, and perhaps technological issues to be navigated in order to truly plug and play data seamlessly across the supply chain.

Any company seeking to adopt the electronic document and data standards set out in the KTDDE must ensure a priori alignment to a company’s own Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) or supply chain data cloud, even when that proprietary data might not be in standardised formats.

The issue impacts both the uploading of data to trade documentation or processes which are standardised, and conversely, the transfer of incoming standardised data or documentations into a company ERP.

Changing the format of data in a company’s ERP might not be feasible – as it would impact historical data, and all data linked to it – not to mention changes in taxonomy, definitions or inclusions.

The problem is magnified by the fact that millions of corporate ERPs might use or harbour unstandardised data – particularly where the company does not already trade internationally.

So clarifying standards for trade documentation might be useful in theory, but in practice, extremely challenging for the company with rudimentary ERPs, i.e precisely those SMEs whom digital trade is supposed to enable.

The same problem exists for supply chain data networks which have addressed the standards and interoperability question by creating their own standards, to which all member parties are contractually bound.

This data might be “unplayable” outside such a network, if it can even be extracted. Again, the interoperable standards question becomes a moot point.

Now, imagine a scenario in which every invoice, order, logistics document, or contract can be automatically understood, and processed, regardless of its origin, and where the data embedded can be extracted in structured, standardised formats.

AI as the missing link

Could AI be the missing link? This is a question that Photon Commerce, a company specialising in AI applications to electronic commerce and trade, aims to address.

First, Photon Commerce’s SmartPDF employs cutting-edge AI, optical character recognition (OCR), and NLP (natural language processing) to transform traditional PDFs into structured, machine-readable formats.

This AI-driven approach automates the extraction and standardisation of key data elements from diverse document types, significantly reducing the time and effort required for manual processing.

The applicability to multiple document types addresses the reality that any solution needs to address the data embedded in over 30 key trade documents of different formats, languages, and data approaches.

More specifically, such solutions could aid in automated processing, accuracy, and interoperability. First, solutions like Photon’s can process thousands of documents swiftly, ensuring they conform to standardised formats and eliminating manual data entry.

Second, the engines become more accurate with more usage. Initially, Photon Commerce trained its AI system on a dataset of over 1,900 trade documents, achieving an F1 score of 0.94. By expanding the training dataset to over 110 million documents, the accuracy improved to an F1 score of 0.98.

Third, because the solution integrates with existing ERP systems – without requiring anything to be changed within that ERP – it may be a more accessible solution because it enables the ERP to “plug and play” with a number of supply chain platforms and approaches.

Photon’s SmartPDF is not the only solution on the market, but it demonstrates how to connect global standards to local markets and their non-standardised practices.

The high accuracy bodes well for AI-driven document processing as a layer to help bridge and potentially solve the problem of interoperability in trade data and electronic documentation.

The author gratefully acknowledges the contribution of the Photon Commerce team, led by CEO Michael Young, to this article.

May: Spotting the innovation frontier for digital trade and finance

The annual BIS Innovation Summit offers a glimpse into how technology might transform finance.

It brings together three key groups:

- Central bankers, who are responsible for managing risk and growth in the current financial system.

- Innovators, technologists, and disruptors who seek to introduce new methods and approaches.

- Large financial institutions, which benefit from the existing system but also recognise the potential for technology to enhance their operations and the movement of money in the modern economy.

This year focused largely on what BIS chief Agustin Carstens called “small steps and gigantic leaps”. Small steps are the innovations which introduce incremental changes, tweaks, and upgrades to existing systems; they are low risk, but deliver returns steadily within today’s operating framework.

Gigantic leaps drive a fundamental rethinking of the entire system in order to transform it for the better, to achieve new goals that become reachable, most commonly due to the rise of new technologies.

Tokenisation: The next big step?

The summit offered insights into three core components of BIS innovation hub’s program: central bank digital currencies (CBDC), tokenisation and smart contracts, and AI.

All three have the potential to both disrupt and drive the digitalisation of trade and finance. Of these three, the first is largely under the purview of central bankers, with the private sector largely following their lead. By comparison, the latter two offer excellent grounds for experimenting with different applications, with the race clearly on to pilot, develop and chart the path to scale.

Tokenisation and smart contracts are a little further ahead than AI, and we can already see how might be able to transform digital trade and finance.

About a decade after blockchain burst into mainstream business media as the killer app for the supply chain of the future, today tokenisation and smart contracts have the potential to realise this promise.

Because tokens carry unique identifiers for assets and owners, they can eliminate the settlement risks created by the need to check, match and clear in any payment situation when paired with smart contracts.

A supplier receives payment a certain number of days after the buyer issues the payment instruction due to several necessary steps. Data must be checked, identities must be matched, and as the payment travels across the globe, delays occur at each stage. Some of these delays are caused by paper processing.

Even when instructions are electronic, human intervention is required to verify all details. As noted by Carstens, these delays incur both monetary and human costs.

By applying tokenisation tied to a smart contract, the transaction can be automated on the basis that certain conditions have been fulfilled. Because the token carries unique but secure data attributes, it can be passed along any number of parties without being connected, and without divulging sensitive information.

Tokenisation can thus not only solve settlement and payment delays, but also helpg financing in multi-tier supply chains, where a buyer may not know a supplier or processor several tiers upstream and for whom financing is critical for executing their part of the supply chain.

Today, that upstream supplier might fall into the $2.5 trillion trade finance gap, and have to resort to money lenders with their costly rates, in order to fulfil the order.

Case studies: Practical application

The application of tokenisation to the trade finance supply chain has already been experimented with the BIS Innovation Hub Hong Kong through its Project Dynamo, which used tokens and smart contracts to finance SMEs upstream in the supply chain.

Payments were triggered by the creation of the electronic bill of lading (eBL), to denote the fulfilment of an order. The Global Shipping Business Network working with ANT group is going one step further, where they have combined the concept of eBL with tokenised deposit through Project Ensemble, spearheaded by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA).

This is the first step towards using blockchain to merge the transfer of title for goods and the corresponding cross-border financial payments between various parties involved in global trade. Trusted trade data (logistics and financial) can also serve as the basis to support trade finance and help bridge the trade finance gap for SMEs.

The trade finance supply chain has long been saddled with many intermediaries: parties who absorb the risk of matching and clearing, money lenders who step in because trade finance does not reach upstream, or local lenders who offer bridge financing for suppliers who might be paid only in delay.

There are also intermediaries within banks, — staff involved in checking, legal and compliance officers who stand guard over SOPs to manage the risk, and so on.

Panelists at the BIS event noted that scaling these new models for finance will deliver a more streamlined financial system, with fewer intermediaries, fewer layers, and more transparency.

In other words, there will be losers, i.e. those who make money from the inefficiencies present today. On a macro level, their elimination means more resources going towards real needs in the real economy, like the millions of SMEs who today cannot find financing.

On the micro level, expect every change to be fought by vested interests whose rents are being jeopardised.

Politics aside, it does appear that the use of tokenisation and smart contracts when applied to eBLs is just a small sliver of the opportunity present in the digitalisation of trade, to drive a better way to finance needs in the world.

Our task is twofold: one, drive the use of eBLs so that that these financing models can be scaled; and two, discover more of these opportunities at every point of the digital supply chain.

April: An interoperability layer for trade finance: Has the time come?

In November 2021, in the wake of intense pressures on trade finance in developing markets as a result of the COVID crisis, McKinsey, the ICC Advisory Group on Trade Finance, and the Fung Business Intelligence proposed a vision to drastically scale up inclusion and interoperability in trade finance.

“Reconceiving the Global Trade Finance Ecosystem” took digitisation of trade and finance as a given, but anticipated that greater challenges would arise unless there was a commitment and an attempt to align divergent approaches on standards, data sharing and governance.

The risk was that fragmentation – the so called “digital islands” effect—would increase rather than be resolved as a result. And meanwhile, the trade finance gap, a measure of financial inclusion, would increase.

Two and a half years later, in spite of the recovery from the covid crisis, the trade finance gap has widened from $1.5 trillion in 2021, to $2.5 trillion, and fragmentation persists.

On the other hand, technology-driven innovation has produced many creative solutions to address the financing gap, including data-sharing platforms, buyer-driven financing, and tokenisation and AI applications to enable deep tier financing. The case for digital identity as a key pillar of the solution has also become clearer.

However, any new solution that proves successful in a pilot or a single market will encounter challenges when expanding across multiple markets, networks, and stakeholders, each with their unique and sometimes varying approaches. There is no easy answer to the scale problem as long as the world of digital trade finance remains balkanised.

At the heart of “Reconceiving the Global Trade Finance Ecosystem” was the proposal of an interoperability layer which would address exactly this challenge, by working to align standards and processes to facilitate data sharing and portability; and serve as a forum for collaboration and coordination on SME inclusion, sustainability, or new emerging issues.

At the time, the proposal of an interoperability layer may have seemed far-fetched, or too ambitious given the immediate pressures of supply chain issues related to COVID. While many may have thought that it was a worthwhile idea, no party was prepared to take the lead to make it happen..

Is it time to revisit the idea of an interoperability layer?

There are two factors that make us think that it is time to revisit the idea.

The first factor is that we have put to rest the idea that standards alignment across the trade ecosystem is “impossible” or too difficult. This week, the ICC DSI will launch the first integrated analysis of all 36 key trade documents (KTDDE), incorporating both B2B and B2G documents, with significant step ups in data alignment and the creation of a key trade data glossary.

It has taken 18 months to accomplish what many considered impossible, given the challenges of integrating various data models and aligning the diverse viewpoints of more than 50 contributing organisations on the requirements for advancing digitalisation..

The soon-to-be-released report is just a start – given that 15 documents still require significant work on digitalisation – but it is a first step against the forces of fragmentation, and sets the basis for the move to transact based on data in the place of documents.

Much more work is required to create plug and play interoperability between the finance documents and data, and the rest of the trade ecosystem which will ensure that finance and trade processes work from a single set of secure, verified, authenticated data.

Secondly, the originally identified fragmentation issues persist, but new issues have arisen as well, many new of which require a greater level of collaboration and coordination.

For instance, the New York state legislature is currently considering amendments to the Uniform Commercial Code, which would provide legal clarity and recognition for digital trade payment instruments in line with MLETR. Across the Atlantic, the French Parliament is also conducting its own hearings on its own alignment to MLETR. These are both key legal underpinnings to trade digitalisation.

Normally such issues would be dealt with by local advocacy, except that both could have widespread impact given the use of New York state law in finance documentation and especially the French decisions on reliable systems (as reported in GTR). These are on regional radars, but what about global radars?

They should be.

The interoperability platform will not replace the good work of industry associations, but rather build on them and ensure complementary actions. And there is a growing list of key issues in digital trade finance needing to be addressed for the good of the industry, such as ESG.

Two and a half years ago, the practice of issuing trade finance based on ESG metrics was not commonplace, given the lack of standard frameworks and the lack of good data. Today, banks race to build such a practice against standards which should be harmonised across the finance industry.

In short, the challenges facing the digitalisation of trade finance are many. An interoperability layer will take effort to build and might not be able to solve all of them, but today, with the sheer scale of need calling out for solutions, it might be a good time to reconsider it.

The KTDDE integrated framework for 36 key trade documents will be launched on Wednesday 24 April at Commodities Week Europe, by the Digital Standards Initiative. The DSI is also involved in an advocacy effort on the New York State legislature consideration of the UCC. They welcome any expressions of interest.

The ICC Digital Standards Initiative will launch a complete framework for “documents to data”, based on its 18 month work on key trade documents and data elements at Commodities Trading Week, April 23 to 25 , 2024. Watch this space!

Digital Trade: From “we need standards” to “let’s drive adoption”

It is now well known that the official deliberations at the recent WTO ministerial meeting (MC-13) produced results that underachieved in the eyes of supporters of digital trade and e-commerce.

To me, this stood in stark contrast to the almost unanimous call for increased digitalisation of trade amongst the business, policy and technology communities heard in the unofficial events alongside MC-13.

Beyond MC13: Digitalisation is still at the forefront

The consensus is growing stronger and clearer: digitalising trade is essential for creating the efficient supply chains we need. Digitalisation checks many boxes: efficiency to deal with rising costs, traceability to deal with increasing requirements at the border; and security and trust, no matter where the documents traverse.

At the regional levels, digital trade is a focus, for instance, as the leading element of the Digital Economy Framework Agreement of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), while the Commonwealth has just launched its trade digitalisation and legal reform working group.

Nationally, the UK passed the Electronic Trade Documents Act just six months ago; a similar bill has just been tabled this past week in France; Australia has recently committed to adopt legal reform measures to allow electronic records in trade within its Simplified Trading System; and China has recently adopted frameworks to experiment with the MLETR in two free trade zones.

For businesses, years of collective efforts to advance the digitalisation of specific processes within supply chains are now yielding results.

This progress is evident in several key developments, including the FIT Alliance‘s declaration on e-Bills of Lading, the World Economic Forum’s launch of the TradeTech initiative, and the growing support for the ITFA’s digital negotiable instrument project.

One might even think that the demise of initiatives like TradeLens, Marco Polo, we.trade and Contour are now no longer strikes against digital trade, but lessons that we as a community must digest en route.

Every call for the digitalisation of trade – whether from business, policy or NGO—seems to be followed by a common refrain that “we need standards,” showing that we all recognise that simply digitising processes individually is not enough.

We hear strong support for combining the many individual initiatives currently underway into one holistic, integrated vision with agreed standards, to enable greater data flow and sharing across supply chains.

This makes a lot of sense. Our work at the ICC DSI shows that over half of the key trade documents used in international supply chains already have harmonised electronic versions or multiple electronic versions whose core data terms can achieve a significant degree of interoperability.

However, if we only concentrate on expanding digitalisation within document-related processes without making an effort to integrate these processes throughout the supply chain, we risk missing out on the significant benefits digital trade offers in terms of equalising opportunities and enhancing efficiency.

In other words, the “standards” referred to in the common refrain will be essential to driving connectivity across the supply chain: first to align data across different processes and secondly, to ensure that the principles for protecting, verifying and authenticating data and electronic documents are consistently applied and thus generate a more trusted, open trade environment.

2024 has every potential to be a turning point in digital trade, with the long work on standards close to being achieved. Indeed, the rousing call “we need standards” is slightly imprecise: the standards already exist at many points across the supply chain.

Our work now is about making these known to those who have the means to drive change, driving adoption as legal frameworks open up, and sharing the gains to deepen capacity for digitalisation where it is in short supply, to make concrete steps towards the digital trade ecosystem that is within our reach.